CONTENTS

NAJISTOTNIEJSZA CECHA JEDZENIA JEST JEGO UMIEJSCOWANIE NA GRANICY WIATA NATURY I WIATA KULTURY.

The most vital attribute of food is its placement precisely on the border between the world of nature and the world of culture.

{Waldemar arski, Ksika Kucharska Jako Tekst}

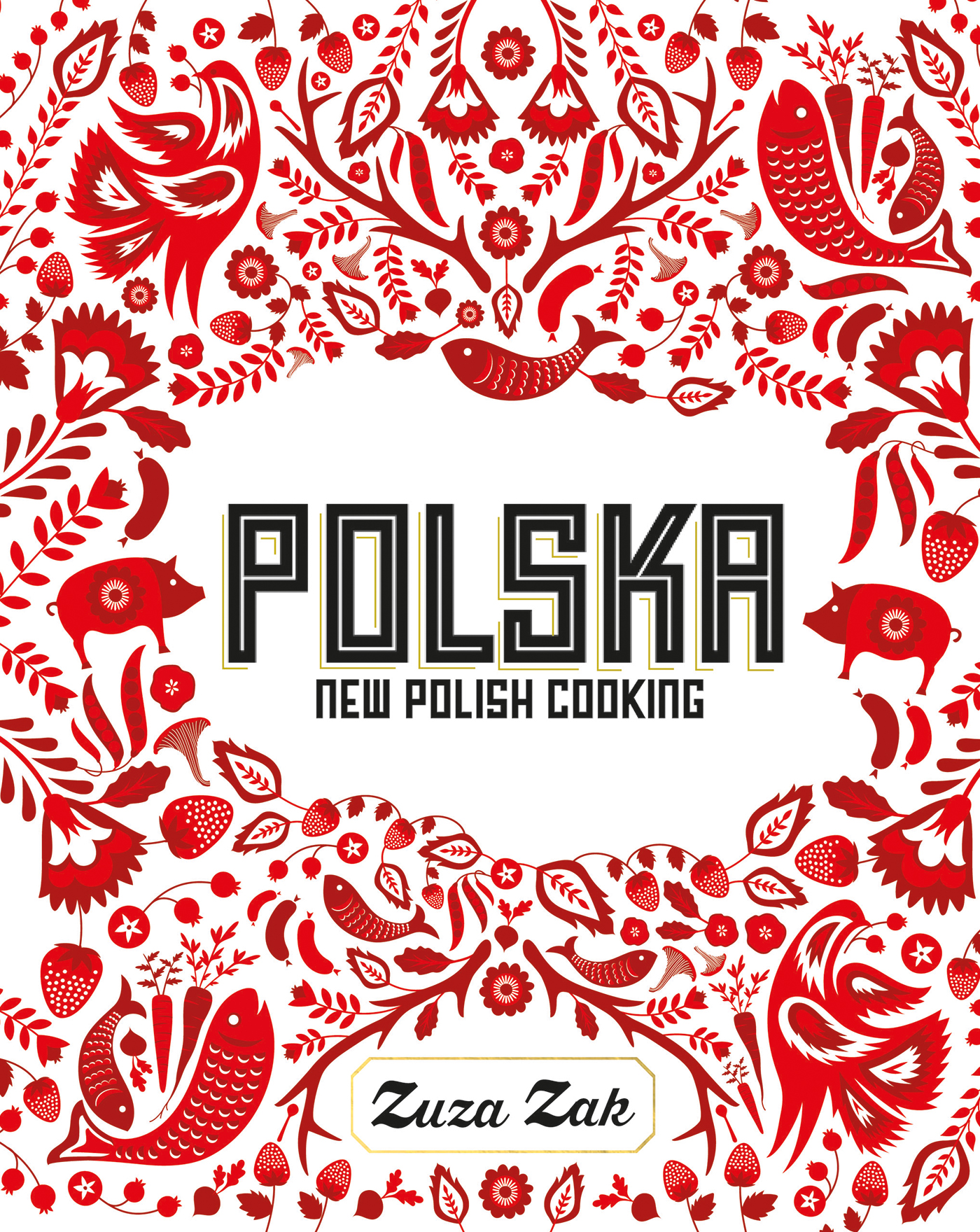

To understand a cuisine is to understand a culture. To understand a culture is to understand the spirit of a nation. The word Poland derives from the word pole, which means field; so even the name of my country is connected with the earth. We define ourselves through our cuisine, which we love deeply, nurture and continue to uphold. Yet it is misunderstood in many parts of the world. Why? Every minority culture faces prejudice and ignorance, yet I believe Polish cuisine, which I remember so fondly from my childhood, is particularly prone to this kind of misalignment.

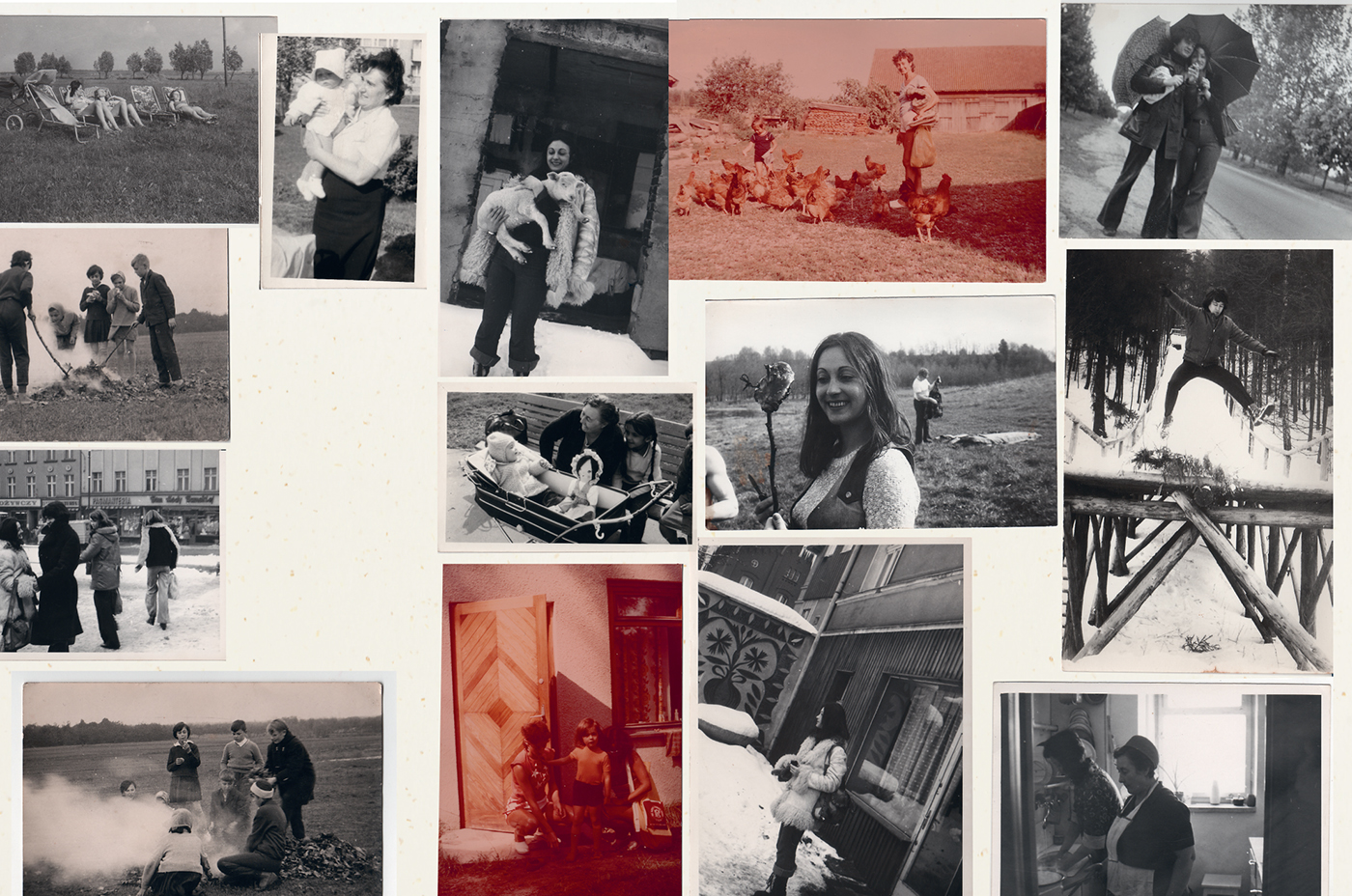

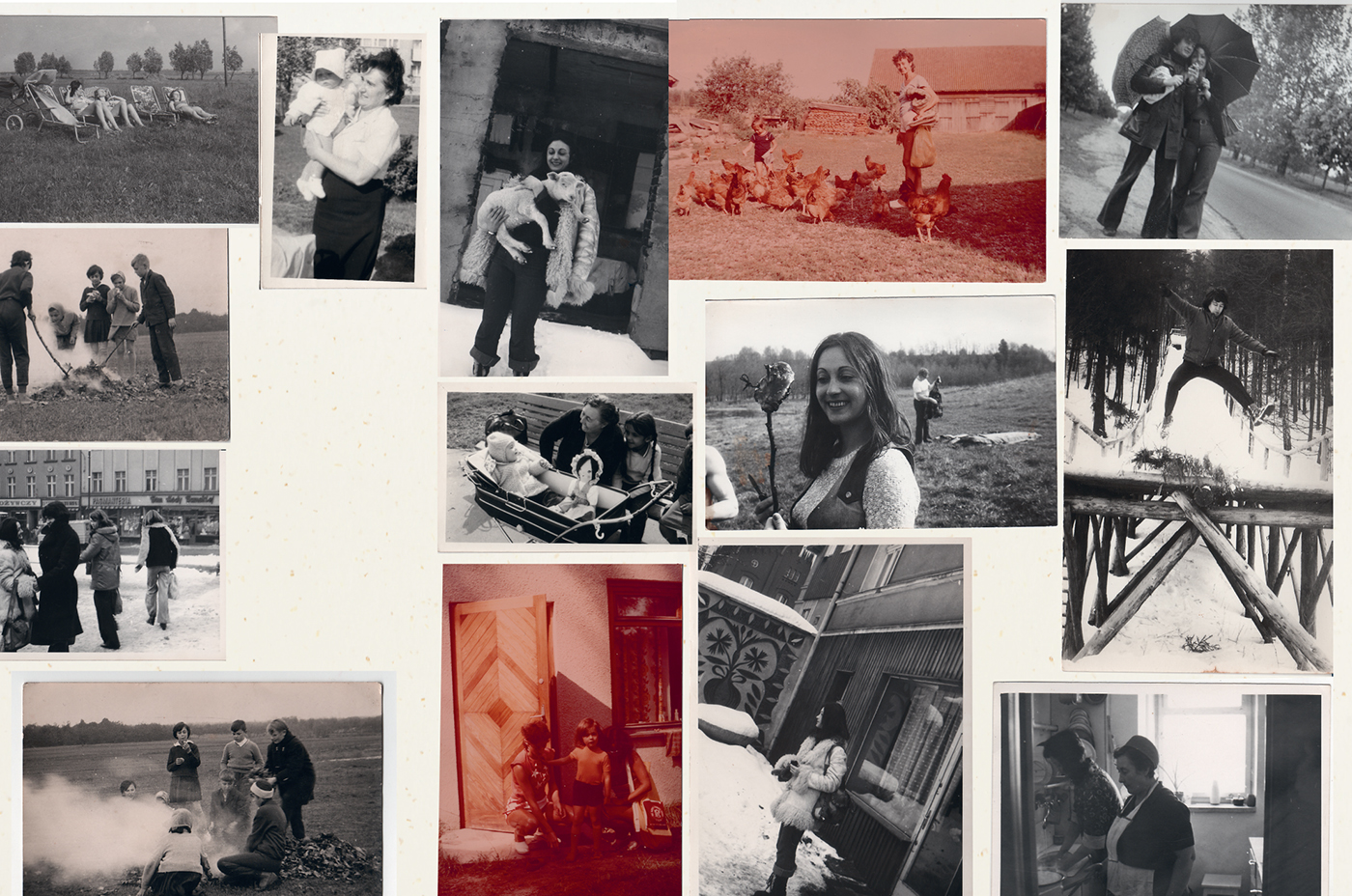

The Slavic culture is one of hospitality; most people prefer to eat at home, or at the homes of friends and family, rather than in restaurants, and it is at home where the best food is found. I have explored my childhood memories spent in Poland during the Communist years and I have also delved deep into Polish history books to gain a real insight into my country; to retrieve traditions that have been forgotten; to compare the colourful folklore of the peasantry with the more refined tastes of the aristocracy; focusing on common threads that run through the soul of this ever-changing nation. For this is a cuisine that has survived the partitions, where Poland effectively ceased to exist for over 100 years and when Communism attempted to exterminate our culture. We survived, not without scars. The countrys sense of loss is palpable, yet trauma has been swept under the carpet of economic growth and development. As quickly as Poland is recovering from its past, and as wonderful as it is to see our people spreading their once clipped wings, it is just as important to remember our roots. Many people have moved through and settled on this land, leaving imprints on our cuisine as they came and went. Despite the unthinkable end to Jewish culture in this area, Chicken soup (ros) is a staple as are many fish and meat dishes which feature Jewish-style variants. This is also true for more transitory ethnicities, such as the many Gypsies that came in and out of Poland throughout the centuries.

When travelling through modern Poland you still get a taste of these historical eras in our food the famous staropolski style that you find in many a karczma (Polish inn) is the old-school traveller fare; the communist years are relived in the milk bars; whereas in the high-end contemporary city restaurant you will find the exciting taste of a modern Poland rediscovering itself.

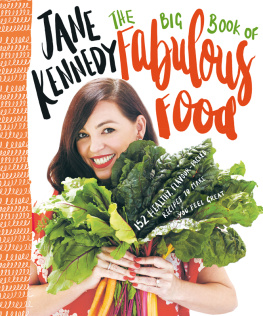

My intention was not to write a typical, traditional Polish cookbook but to create something contemporary, a love letter to the country I left behind.

This book is my journey.

HISTORY

POLSK EMY PRZEJEDLI I PRZEPILI

Too much eating and drinking cost us our Poland.

[Polish proverb]

This proverb beautifully describes the Polish love of food, drink and parties, which often led to us not being in the right frame of mind to defend our country from attack. Considering the number of enemies Poland had (both outside and within), its understandable that we turned to these simple pleasures as a distraction from continual bombardment.

the enemies have nothing in common but the desire to annihilate us when some hordes depart others immediately appear Goths, Tatars, Swedes, imperial legions.

[Zbigniew Herbert]

Polish cuisine, like the countrys past, is rich and varied. The geography, the rulers, migration, even the ongoing political turbulence and war have all brought with them culinary changes and developments. Being on the central plain between East and West, Poland has always been geographically vulnerable to invasion; historian Norman Davies dubbed it Gods Playground.

The beginning of Polish history, as we know it, is marked by a feast. The feast was given by Piast, a ploughman of Prince Popiel, during the ancient right of hair clipping (the pagan equivalent of a christening). Two strangers knocked on the door of his modest household, having been refused entry to the castle of the mean-spirited Prince Popielo. Although his feast was modest, Piast welcomed the strangers into his abode. The strangers turned out to have magical powers and made the food and drink grow and multiply creating a fantastical feast that the guests remembered for the rest of their lives. Once hed grown up, the son of Piast, the lucky Siemiowit, drove out the Popiel prince, and formed the first Polish ruling dynasty called the Piasty Clan. This feast was the stuff of dreams and legends, yet it offers a perfect example of the Polish art of hospitality and entertaining. Everyone is welcome. Food and drink is to be shared amongst friends and strangers alike, snobbery or any kind of exclusion is unacceptable.

When talking to my grandmother about the ruling dynasties of Poland, I was surprised to learn that aside from the foremost Piasty clan, all Polish royalty had hailed from other countries. The Italian Queen Bona brought with her many vegetables (indeed the Polish word woszczyzna which we use to describe vegetables, comes directly from our word for Italy); the famous Jagiellonian Dynasty started with the pagan Lithuanian King Jagiello and the Polish-Hungarian Queen Jadwiga, who left both Lithuanian and Hungarian traces on our cuisine and culture, Jan III Sobiecki brought Asian influences; and during the reign of the last Polish King, Poniatowski, French cuisine was la mode. Poniatowski was also a lover of Catherine the Great of Russia, who it is said, placed him in his position of power. But it was the peasant cooking of Russia which had the greatest influence on our Polish cuisine, and that of course came from the common people rather than the royal court.

In addition, we cannot ignore the Polish Catholic bond with the Papal See. The church officials and urban elites looked to Italy for influences in every area of life, especially the kitchen. By the 18th Century, Polish aristocrats were writing about a golden age of Polish cookery, yet the dishes they wrote about were mostly from Tuscan or Milanese descent, adapted to suit Polish ingredients and tastes.

MEDIEVAL POLAND

The horse-bound, nomadic Tartars were a constant threat as their fierce hordes rampaged our lands on a regular basis, attacking the Slav settlers. Their culture has had an undeniable impact, reflected in dishes such as Steak Tartare originally made from horsemeat minced under their saddles and Tartar sauce which is now commonplace European fare.