The Talmud

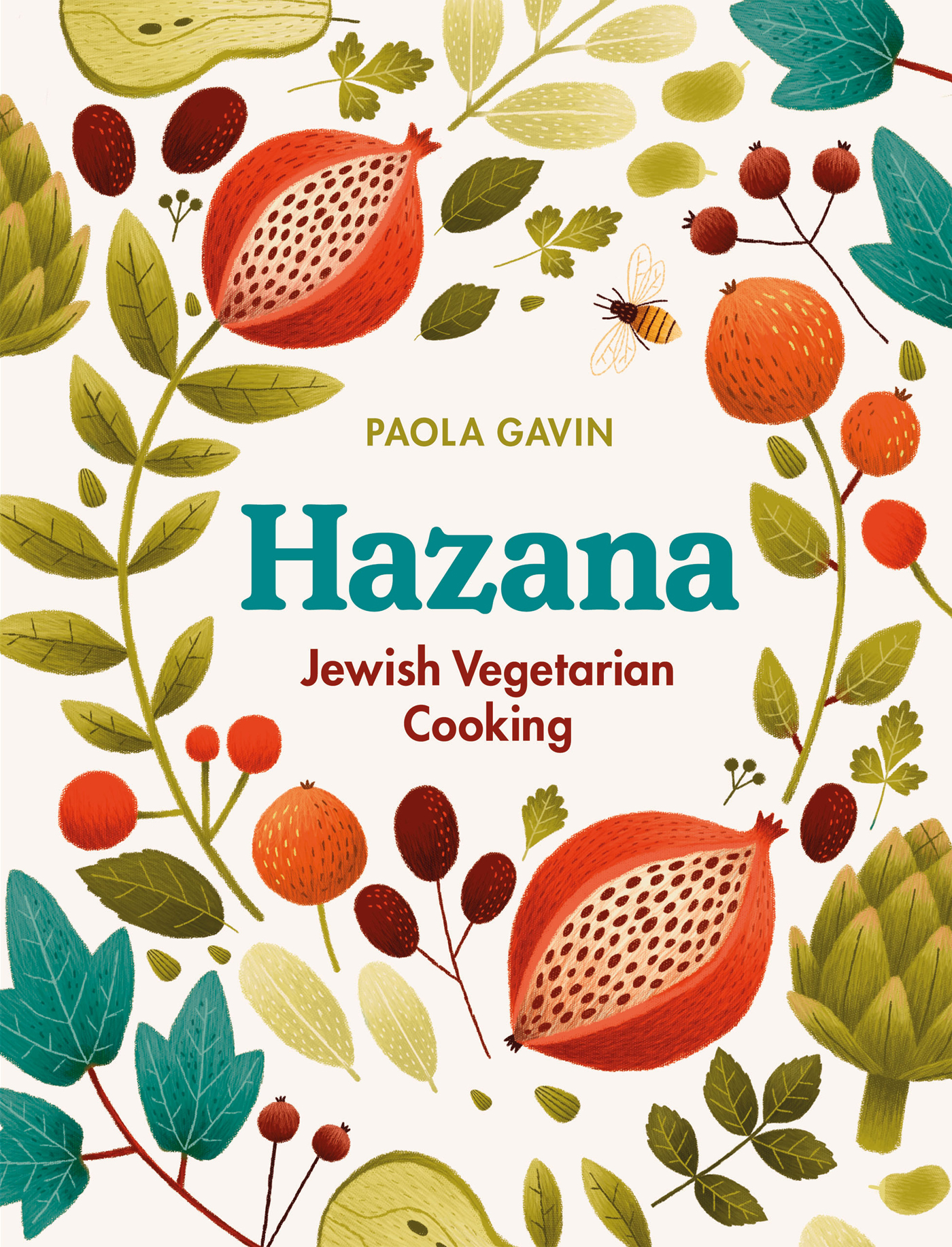

Over their two thousand years of exile, Jews migrated across the world, taking their culinary heritage and traditions with them. Wherever they went, they adapted local and regional dishes to fit their own strict dietary laws and, as a result, Jewish food today encompasses an enormous variety of cuisines and cooking styles. This book is a personal collection of traditional Jewish vegetarian dishes from around the world. The recipes I have chosen have been passed on from mother to daughter for generations, and are quick, easy to prepare and healthy.

The Jewish concept of vegetarianism dates back to the days of the Garden of Eden. Under traditional Jewish law it was forbidden to kill an animal, just as it was to kill a man. In Judaism, as in Hinduism, the eating of meat is thought to increase the animal nature of man, and Jews are forbidden to eat any meat in which its lifeblood still runs as this is thought to contain the spirit, emotions and instinct of the animal.

The diet of the ancient nomadic Israelites was predominantly vegetarian. Sheep, goats and cattle were too highly prized for their milk production to be killed for their flesh, so livestock was mainly slaughtered for ritual practices. When the Hebrews fled to Egypt, they adopted new eating habits: Egyptians taught them the art of making leavened bread, and they soon shared the Egyptian love of cucumbers, melons, leeks, onions and garlic.

After the Jews arrived in the Holy Land they became farmers, growing wheat, barley, rye and millet. The food of the poor was based on bread, pulses especially lentils, broad (fava) beans and lupins - goats and sheeps cheese, olives and olive oil, nuts, vegetables and herbs, and fresh and dried fruit. Food was usually sweetened with honey or syrup made from figs, carob beans or dates; at that time, Jericho was famous for its dates and was nicknamed the city of palm trees.

One ancient Jewish sect the Essenes were staunch vegetarians. The mostly male sect existed in the second century BC. It was formed in reaction to the rigidity of Jewish religion of that time. The word Essene derives from the Hebrew word esau, meaning to be strong, and presumably this referred to their strength of mind, the renunciation of material comforts and repression of sexual desire. John the Baptist is said to have been an Essene, and there are some people who believe that Jesus spent some of his early years with the Essene community.

There are four main Jewish communities across the world: the Mizachrim, or Easterners, whose ancestry is from the Middle and Near East, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and India; the Ashkenazim, who settled in the Rhineland after the diaspora and then migrated across Eastern Europe to Russia and the Ukraine; the Sephardim, or Spanish Jews, who settled around the Mediterranean after fleeing the Spanish Inquisition; and the Italkim, Italian Jews who were brought to Italy as slaves by the Roman Emperor Titus, following the destruction of the Second Temple.

Nevertheless, close trading and cultural connections mean that these cuisines often have similarities. For example, there are strong ties between the Jews of Tunisia and those of Livorno in Italy which is reflected in their cooking. The Italian cuscussu is obviously of North African origin, while the Tunisian boka di dama (almond sponge cake) clearly has Italian roots.

Ultimately, Jewish cooking is food cooked according to the Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws), that forbid the consumption of meat and milk at the same meal. In Orthodox Jewish households, separate plates, utensils, pots and pans are used for milk and meat. Milk products cannot be eaten after meat until an interval of time has lapsed. This can vary from 2 to 6 hours according to local tradition. Neutral food, such as milk-based bread, fruit, vegetables and unfertilized eggs can be consumed with meat or milk.

Researching this book has been a great opportunity to discover the history and culinary heritage not only of my own family who originally came from Poland and Belarus but also to trace the history and culinary traditions of Jews from so many different parts of the world. One thing we all have in common is the same love of food and cooking, something that lies at the heart of Jewish life.

THE SABBATH

Shabbat

The Sabbath is a weekly day of rest, beginning on Friday just before sundown and ending just after dark on Saturday, when the first three stars can be seen in the sky. During the Sabbath all work is forbidden. Work covers thirty-nine actions, ranging from the lighting of a fire, cooking and baking, to the answering of the telephone. The Sabbath is always ushered in by the lighting of candles, before blessings are said, first over wine and then over a challah (braided egg-enriched bread) that is traditionally covered with a white cloth.

Sabbath meals need to be prepared, or at least partly cooked, before sunset on Friday, and ingenious ways were found to accommodate this. One-pot meals and stews that were cooked very slowly overnight were invented, such as the Sephardic dafina and Ashkenazi cholent. Other well-known Sabbath dishes include the Ashkenazi borscht (beetroot soup), krupnik (mushroom and barley soup) and kugels (sweet or savoury puddings); and the Sephardic huevos haminados (slow-baked eggs) and borekas, bulemas, pastels and filas (cheese or vegetable pastries). Italian Jews often prepare stuffed vegetables, caponata or minestrone soup for the Sabbath.

THE NEW YEAR

Rosh Hashanah

Rosh Hashanah falls around the end of September or early October (on the first two days of the Hebrew month of Tishri), and marks the beginning of the Ten Days of Repentance, which end with the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur). Jews believe there is a Book of Life in heaven, in which all our thoughts, words and deeds are recorded. During the Days of Repentance, this book is examined and everyones fate for the coming year is decided.

Traditional foods served for Rosh Hashanah are black-eyed beans (peas), leeks, beet greens, gourds and dates. It is customary to eat challah or a slice of apple dipped in honey, and to say a prayer for a sweet New Year. Sometimes pomegranates are served, as their plentiful seeds symbolize good deeds for the year ahead. Ashkenazis also like to serve carrot tsimmes (a sweet stew) as a symbol of good luck, kugels, lekach (honey cake) and teiglach (pastry nuggets cooked in honey). Sephardic Jews prefer rice pilafs, almodrote (gratins) and pastries soaked in sugar syrup. Nothing sharp or bitter is served for New Year, nor anything black, because of its association with mourning.

THE DAY OF ATONEMENT

Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur is the most solemn and holy day of the year, a day of fasting and reflection. The last meal before the fast is served in the late afternoon of the eve of Yom Kippur, and it never includes salty food, as it is not easy to fast when you are thirsty. In Egypt this meal often begins with an egg and lemon soup. Ashkenazis often prepare a broth with