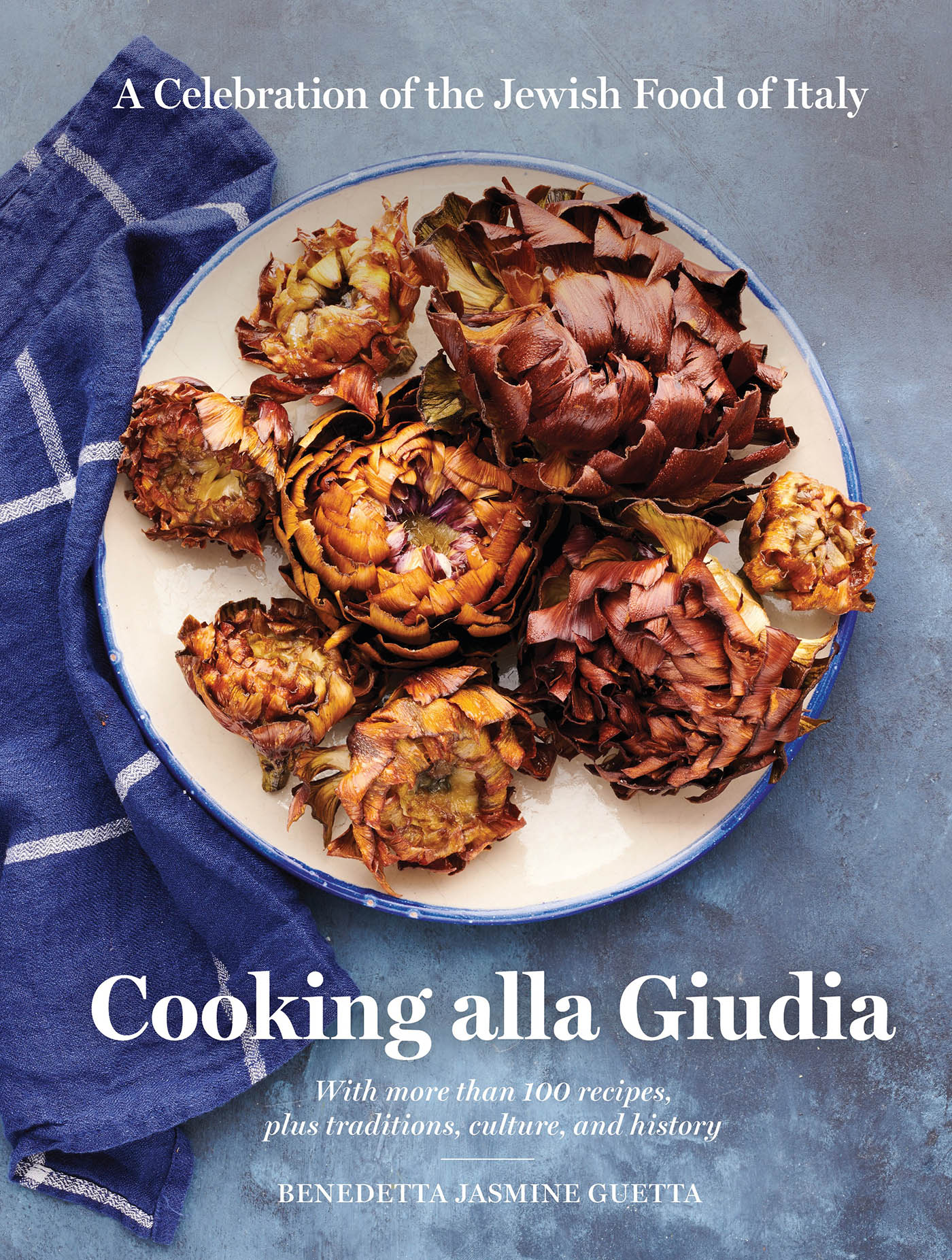

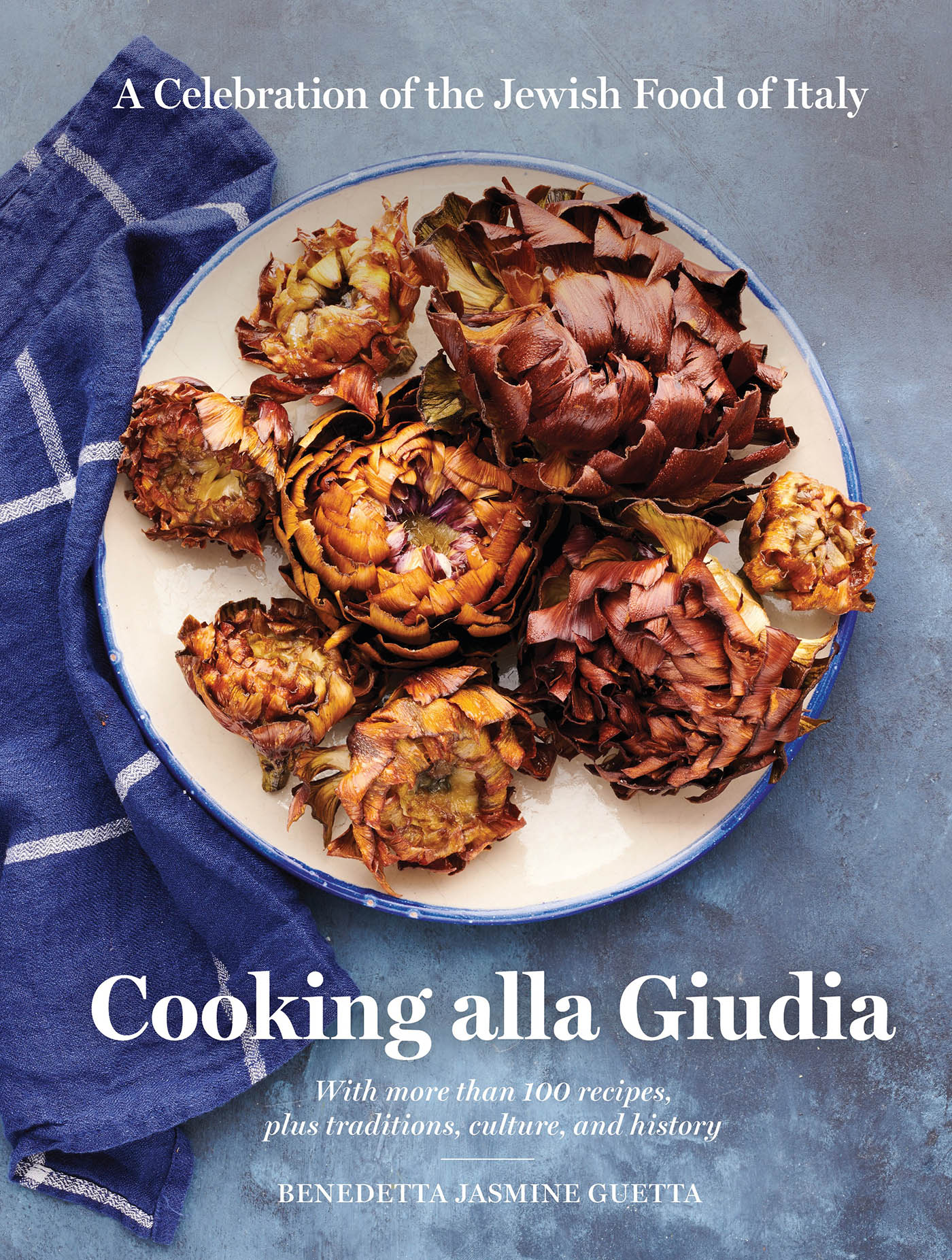

A Celebration of the Jewish Food of Italy

Cooking alla Giudia

Benedetta Jasmine Guetta

Artisan Books | New York

To my mother,

who taught me everything

To Shlomi,

who gave me the courage to dream up this book

To Maya,

who will carry these recipes into the future

Contents

Introduction

This book is a tribute to the wonderfully rich but still mostly unknown culinary heritage of the Jews of Italy. While Jews have lived in Italy for thousands of years, the depth of their contribution to Italian cuisine today has been largely untold.

When describing one of the most popular cuisines in the world, its tempting to paint Italian food with a broad brush: everyone agrees on the culinary merits of lasagna, pizza, cannoli, and tiramisu, no questions asked. However, the patchwork of subtleties that comprise Italys mosaic of traditional dishes is often unfairly overlooked, even by native Italians. In order to properly understand Italian food, its essential to consider the crossroads between Italian and Jewish culture. Jews, after all, have lived in the region since the days of ancient Rome, and through the ages, they have changed the way Italians eatcertainly for the better! For instance, if you ask someone in Italy about the origin of orecchiette pastathe signature ingredient of the southern region of Apuliamost would state with absolute certainty that it comes from Southern Italy. Well, it turns out it most probably came from Provence, in France, brought by the Jews who settled in Apulia as early as the twelfth century.

Farther north, in the region of Veneto, one of the classic specialties of Venice is sarde in saor (sweet-and-sour sardines). Proud locals would surely swear that sarde in saor is a Venetian dish, but from the ingredients of the dishespecially the combination of raisins and vinegarwe know that the recipe must have been brought to Veneto by the Sephardic Jewish merchants who traveled to Italy from Spain.

The Jewish influence on Italian food goes well beyond dishes and recipes; it goes all the way back to the ingredients themselves. A classic example is the story of the adoption of eggplant by Italians. Today we know melanzane as a key ingredient in many Italian dishesthink of eggplant parmigianabut this wasnt always the case. In the late Middle Ages, Jews in Spain learned from the Arabs how to cook eggplant, an ingredient that was practically unknown to the inhabitants of Italy. When the Jews were expelled from Spain, many of them relocated to Italy and brought with them their traditions and customs, including these bizarrely shaped vegetables. Berenjenas, as they were called in Spanish, were regarded by Italians with great suspicion. Eggplants were disdained for ages as food suitable only for the Jews and for the poormany people even thought they were poisonousuntil the end of the seventeenth century, when Italian Christians slowly began to appreciate Jewish specialties like melanzane in concia (fried eggplant with vinegar) and thus adopted them in their cooking.

Just as Jews have shaped Italian cuisine, so has Italywith its own ingredients and flavors, but also with its economic and political landscapeshaped the way its Jewish citizens cook and eat. Just look at zuppa di pesce (fish soup), a specialty of Italian Jewish cuisine that is greatly appreciated in Rome. In 1555, Pope Paul IV ruled that the thousands of Jews living in Rome had to move to a ghetto, a confined area located in one of the most undesirable quarters of the city, near the old fish market, and subject to constant flooding from the Tiber River. The conditions in the ghetto were terrible, with most of the Jews living in extreme poverty. However, the Jewish women there, demonstrating that necessity truly is the mother of invention, made the most of their dire circumstances. They would go to the fish market after it closed, collect all the heads and tails and other leftovers that the fishmongers had disposed of, and boil them in water to make a soup. This is the humble origin of zuppa di pesce, a staple in the Jewish Quarter in Rome that is now considered a local delicacy.

These are just some of the fascinating facts about Jewish Italian cuisine that can be uncovered by looking through the dusty recipe books of Italian Jews; they provide evidence of how migration, poverty, and even oppression can, over time, give rise to some extraordinarily delicious food. Knowing the stories behind the dishes makes them taste even better.

A Brief History of Jews in Italy and Their Cuisine

Jewish food all over the world, be it Sephardic, Mizrahi, or Ashkenazi, has developed in accordance with the historical and geographical circumstances of the Jews in the Diaspora. In this respect, Jewish Italian food is no exception: the birth and evolution of the Jewish Italian culinary tradition have been closely linked over the centuries to the history of the Jewish communities in Italy, and to the history of Italy as a whole.

Jews arrived on the Italian peninsula back in the Republican age of Rome. During the Jewish-Roman wars, beginning in 66 CE and spanning seventy years, thousands of Jews were taken from Jerusalem to Rome as slaves, an event depicted in images on the famous Arch of Titus, near the Roman Forum. The Jews were treated with tolerance by most of the Roman emperors, so their numbers swelled to more than fifty thousand in the first century, when they occupied urban centers and port towns, often earning their freedom and becoming merchants. However, when the emperor Constantine decriminalized Christianity in 313 CE and subsequently converted, he paved the way for Central Italy to become what it is today: the seat of the papacy.

The Roman Empires collapse in the late fifth century resulted in the creation of a number of separate states, each with its own political landscape, a situation that characterized Italy until the late 1800s, when the country was finally unified. Jews were dealt with differently by the Christians in each state, and those differences determined the way they lived and, naturally, cooked. Italian Jews were also often expelled from one state and relocated in another one, but this forced mobility allowed for the expansion, rather than decline, of their culture.

Central and Southern Italy (in particular the region of Sicily and the city of Rome) were home to the earliest and largest Jewish communities in the country until the expulsion of the Jews in the late fifteenth century. Because Sicily was a major hub for commerce with Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries, Sicilian Jews had long traded with the foreign occupiers who, over time, contended for Italy, including Arabs, Normans, Angevins, and Aragonese. From the Arabs, the Jews of Southern Italy learned to cook with ingredients previously unknown in the country, such as artichokes, eggplants, fennel, and cardoons, as well as many spices that later came to be identified as Jewish ingredients by the local population. When the Spanish monarchy banned the Jews from its kingdom in 1492, thousands of Jews who lived in Sicily fled north, expanding their cultural influence all over the peninsula. While the original Jewish settlements in Southern Italy disappeared, their culinary traditions survived, though in somewhat diluted form, and spread to other regions.

Next page