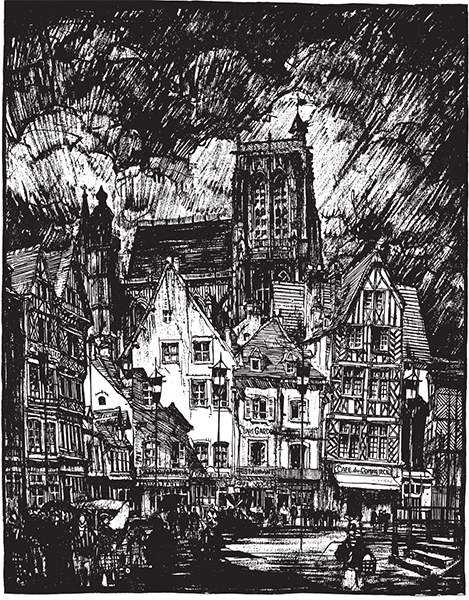

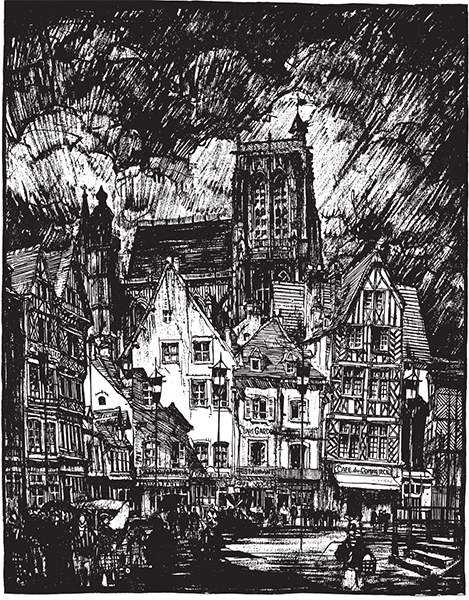

T REASURY OF A MERICAN P EN-AND -I NK I LLUSTRATION 1881 TO 1938 236 D RAWINGS BY 103 A RTISTS E DITED BY F RIDOLF J OHNSON DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC. MlNEOLA, NEW YORK Frontispiece: Samuel V. Chamberlain (8951975), "Abbeville." Copyright Copyright 1982 by Dover Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. Bibliographical NoteTreasury of American Pen-and-Ink Illustration, 1881 to 1938: 236 Drawings by 103 Artists is a new work, first published by Dover Publications, Inc., in 1982 andreissued in 2014. 1. 1.

T REASURY OF A MERICAN P EN-AND -I NK I LLUSTRATION 1881 TO 1938 236 D RAWINGS BY 103 A RTISTS E DITED BY F RIDOLF J OHNSON DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC. MlNEOLA, NEW YORK Frontispiece: Samuel V. Chamberlain (8951975), "Abbeville." Copyright Copyright 1982 by Dover Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. Bibliographical NoteTreasury of American Pen-and-Ink Illustration, 1881 to 1938: 236 Drawings by 103 Artists is a new work, first published by Dover Publications, Inc., in 1982 andreissued in 2014. 1. 1.

Pen drawing, American. 2. Pen drawing19th centuryUnited States. 3. Pen drawing20th centuryUnited States. I.

Johnson, Fridolf. NC905.T73 741.973 81-19535 e ISBN-13: 978-0-486-79151-7 Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation 24280305 2014 www.doverpublications.com INTRODUCTION The art of pen draftsmanship, once so widely practiced in the illustration of books and magazines, appears to be enjoying a revival of sorts as numerous contemporary illustrators rediscover the remarkable versatility of the pen as an illustrative medium. Nearly all of the great pen draftsmen of a few decades ago are gone; many are forgotten except by specialists, their work buried in files of old magazines and in books no longer read. Now is a good time to attempt a general survey of American pen drawings produced during the "Golden Age of Illustration" the period from the early 1880s to the late 1930s. In the long history of the graphic arts, the direct reproduction of pen illustrations has a span of only a hundred years. It was in the middle of the 1880s that wood engraving, a laborious and not very satisfactory method of reproducing pictures, began to be supplanted by the photoengraving process, which for the first time permitted the mechanical translation, photographically reduced or enlarged as desired, of an artist's original pen drawing onto a metal plate for ordinary letterpress printing.

Felix Octavius Darley (18221888), one of America's most popular illustrators of his time, came along too late to benefit from the new process; all his drawings were engraved by hand. But there was a younger generation of illustrators, their earlier works also engraved on wood, who were eventually to see their line drawings reproduced by photoengraving in almost perfect facsimile. Encouraged by the unprecedented fidelity of reproduction, their ranks were joined by many other young artists, laying the foundation for an American school of illustration rivaling the best of Great Britain and the Continent. Ironically, the same technology that nurtured the flowering of pen illustration eventually brought about its decline. The almost simultaneous invention of the halftone screen made it possible to reproduce a photograph or painting by splitting up the tonal values photographically into graduated dots, chemically etched on a printing plate. Soon halftone illustration was more popular than line.

Many artists, failing to master the pen, found it more expedient to make wash drawings exclusively, but until the 1930s there were many others who were able to achieve brilliant techniques for rendering in line alone. To the dismay of wood engravers and the delight of the reading public, publishers capitalized on the cheaper and less cumbersome photoengraving process by using it to fill their books and magazines with pictures. After 1890 a magazine formerly spending some $5,000 a month on wood engravings alone could greatly enlarge its pictorial content for less than $2,000 a month with the new process. The profusion of good illustrations brought larger circulations to magazines. By 1893 Cosmopolitan had reached a distribution of 300,000; by 1895 Munsey's had risen to 400,000. Century, Scribner's, Harper's, St.

Nicholas and many other magazines responsive to the expanding market for recreational reading also prospered. Book publishers, especially in the early 1900s, issued popular novels in decorative bindings and complete with the illustrations that had first appeared in their serialization in magazines. Thus many illustrators had the double advantage of having their work reproduced in permanent form as well as in more ephemeral publications. The pen, as an instrument for drawing and writing, has a long history, beginning with the Chinese, who made pens out of bamboo, shredded out at one end into a brushlike tip. Later the Egyptians made a similar pen-brush out of reed for writing on papyrus. The earliest pointed pen was the Greek or Roman stylus, a sort of bodkin made of metal, bone or ivory for writing on tablets covered with wax.

The quill pen, made from the hollowed wing feathers of birds, dates from the seventh century AD. and is the true forerunner of the modern pen (the name being derived from the Latin penna, meaning feather). It was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that pen points made of steel, their nibs split to make them more flexible, were common enough to be found in nearly every household. For handwriting, in that age of self-conscious elegance, full advantage was taken of the pen's flexibility to produce the swelling curves of superfluous flourishes for decorative effect. For early illustrators drawing for reproduction, however, there was little reason to pay attention to the quality of lines not likely to be faithfully duplicated on wood. Many illustrators were content to draw the general outlines of a composition, indicating values with a brush (sometimes directly on the block) and trust the wood engraver to flesh it out, shading and all, according to his capabilities.

This was common practice among artist-reporters for the illustrated weeklies. Tight deadlines and the inconvenience of working "on the spot" precluded anything more than rough sketches with scribbled instructions for a staff artist or engraver to fill in details. Even after it had been made possible to transfer a pen drawing photographically onto a photosensitized hardwood block for the engraver to cut into, a con scientious artist was often disappointed with the final result. Just the same, of the hundreds of craftsmen busy making wood engravings during the latter half of the nineteenth century, there were many with the extraordinary skill and judgment required to duplicate every line and squiggle with remarkable fidelity and spirit. With the advent of photoengraving, illustrators could no longer depend upon wood engravers to "clean up" their haphazard drawings and perforce found themselves suddenly on their own. The lesson that a poorly executed drawing made an equally poor reproduction was a strong incentive to mastery of pen technique.

As some of the early examples in this survey reveal, the graphic potential of the flexible pen was at first imperfectly realized and the general tendency was to wield it like an etching needle. There is an absence of bold or spontaneous strokes; shading and values are built up of many fine lines and close crosshatching, even in the darkest areas, where a few passes of an ink-loaded brush would have served the purpose more directly. Except for the sparkling whites in the untouched areas, the effect is quite similar to that of an etching. This is particularly evident in the drawings of many artists whose earlier work had been engraved on wood: Rufus Fairchild Zogbaum (pp. 8 & 9), a specialist in military subjects; Clifford Carleton (p. 10 & 11) and S. W. W.

Van Schaick (p. 35), who preferred the social scene. Illustrators addicted to rendering in fine pen lines ran the risk of having the faintest of them etched away in the plate. Joseph Pennell, in Pen Drawing and Pen Draughtsmen, first published in 1889, pays high tribute to Edwin Austin Abbey (pp. 2 & 3) as an illustrator but writes that a vital strong line meant little to this artist and that he "coaxed his forms out of the paper with his pen, but did not put them directly down," and complained that his drawings "became so refined that no process line-engraving can reproduce every line." Indeed, for a de luxe edition of

Next page

T REASURY OF A MERICAN P EN-AND -I NK I LLUSTRATION 1881 TO 1938 236 D RAWINGS BY 103 A RTISTS E DITED BY F RIDOLF J OHNSON DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC. MlNEOLA, NEW YORK Frontispiece: Samuel V. Chamberlain (8951975), "Abbeville." Copyright Copyright 1982 by Dover Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. Bibliographical NoteTreasury of American Pen-and-Ink Illustration, 1881 to 1938: 236 Drawings by 103 Artists is a new work, first published by Dover Publications, Inc., in 1982 andreissued in 2014. 1. 1.

T REASURY OF A MERICAN P EN-AND -I NK I LLUSTRATION 1881 TO 1938 236 D RAWINGS BY 103 A RTISTS E DITED BY F RIDOLF J OHNSON DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC. MlNEOLA, NEW YORK Frontispiece: Samuel V. Chamberlain (8951975), "Abbeville." Copyright Copyright 1982 by Dover Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. Bibliographical NoteTreasury of American Pen-and-Ink Illustration, 1881 to 1938: 236 Drawings by 103 Artists is a new work, first published by Dover Publications, Inc., in 1982 andreissued in 2014. 1. 1.