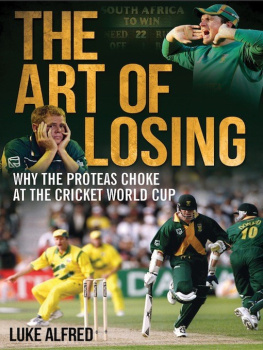

THE

ART OF

LOSING

THE ART OF LOSING

WHY THE PROTEAS CHOKE

AT THE CRICKET WORLD CUP

LUKE ALFRED

Published by Zebra Press

an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd

Reg. No. 1966/003153/07

Wembley Square, First Floor, Solan Road, Gardens, Cape Town, 8001

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa

www.zebrapress.co.za

Publication Zebra Press 2012

Text Luke Alfred 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners.

PUBLISHER: Marlene Fryer

MANAGING EDITOR: Robert Plummer

EDITOR: Bronwen Leak

PROOFREADER: Mark Ronan

INDEXER: Sanet le Roux

ISBN 978 1 77022 384 4 (print)

ISBN 978 1 77022 385 1 (ePub)

ISBN 978 1 77022 386 8 (PDF)

Acknowledgements

MANY people offered their time and patience in helping me with this book. Alan Jordaan, the manager of the team to the 1992 World Cup, gave me two long interviews, both of which were extremely helpful in getting me started and planting the creative seed. Geoff Dakin was pestered on the phone on several occasions. He was always up to the task despite a family bereavement. Thanks, Alan and Geoff.

Thanks, too, to Steve Palframan, a man with a fine memory and many stories. He could have talked for far longer and graciously allowed me to borrow from his video collection of the 1996 World Cup, which was exceptionally helpful.

Boeta Dippenaar also took time off from the glamorous life of being a freelance helicopter pilot to give me a thoughtful, thought-provoking interview. He went on to answer several subsequent queries. Thanks, Boeta.

Of the former international cricketers (or those associated with the international game) I spoke to, I was given a particularly fruitful and insightful interview by then acting Dolphins coach, Lance Klusener. I was also given a candid two-hour audience by former Proteas coach Corrie van Zyl. Kepler Wessels and Meyrick Pringle were helpful, as were Craig Matthews, Peter Kirsten, Peter Pollock and Herschelle Gibbs. Thanks, guys, for your time and commitment.

Derek Crookes was fine value, too, for an extended interview over several cups of coffee in Bryanston. Im grateful, Derek.

Through the cricket season I also did telephone or email interviews, some of them long and all of them useful, with Neil Johnson, Justin Kemp, Ashwell Prince, Adi Birrell and Nicky Boje. Thanks for your energy, guys and your zest, Johnno.

As far as other administrators and media liaison men were concerned, a heartfelt thank you to Cassim Docrat, Gerald de Kock, Robbie Muzzell, Arthur Turner, Tony Irish and Gordon Templeton.

I was helped, as well, by John Young and his memories of the late Bob Woolmer, and by UCTs Sports Science Institutes Clinton Gahwiler.

Thanks, too, for the excellent lunch at Sophias, Lee Irvine and the numerous cups of coffee, Ali Bacher.

Former and current members of the hardened corps of South African cricket journalists also offered memories, suggestions and advice. Thanks, guys, particularly John Bishop, Telford Vice, Fanie Heyns, Heinz Schenk and Altus Momberg. You were very helpful, as were the staff of the Avusa library in Rosebank, especially Michelle Leon and her team.

The guys at SA Sports Illustrated were quick to respond to my requests. I dont want to blow your cover by mentioning you by name, but you know who you are.

I would also like to acknowledge a structural debt to fellow author Ed Smith. In his book What Sport Tells Us About Life, he makes use of the Josh Rudder example of empirical learning that I borrow and expand upon in my conclusion.

The biggest debt, though, is owed to Andrew Samson, Cricket South Africas official statistician. Andrew helped me too many times to mention with answers to a range of sometimes bizarre statistical queries. Thanks, Andrew.

Thanks finally to Richard Pybus, a good friend and fellow fan of the great game, and Bronwen Leak and Robert Plummer at Zebra Press for their hard work and support. And to my wife, Lisa her love shines with a strong and unyielding light.

LUKE ALFRED

KENSINGTON, JUNE 2012

Introduction

We live in an age obsessed with success, with documenting the myriad ways by which talented people overcome challenges and obstacles. There is as much to be learned, though, from documenting the myriad ways in which talented people sometimes fail.

Malcolm Gladwell, The Art of Failure

THIS is a book about failure. It is also a book about ghosts, and about how ghosts tend to haunt even the brave and strong-willed, the courageous and the noble. South Africa have played in six 50-over World Cups since 1992 and have not reached the final in any of them, despite hosting the tournament in 2003 and arriving at some of the tournaments either as the top-ranked side in the world or on the back of an impressive winning streak as they did in 1996. All this begs the question how, with such a fine side regularly at its disposal, can South Africa not win at World Cups? Clearly something is wrong.

Is it because of behind-the-scenes bungling, poor selection or changing key personnel, like coaches, too close to major tournaments, as was the case with Corrie van Zyls appointment a little over a year before the 2011 World Cup? Is it because of a cricket culture that somehow feels residually but fundamentally entitled to victory, given that when South Africa played their last Test cricket before banishment in 1970, the national side thumped Australia 4-0? Do we believe we have a preordained right to win, in other words? Or does the shadow of the past haunt South African cricket to a degree that is still felt but seldom acknowledged? Can a team that represents the nation not function at optimum levels if the nation doesnt somehow feel itself to be a nation at all? After all, how can a game as starkly existential as cricket not fail to mirror the anguish and unfinished business of a newly democratic society as a whole, an anguish that the national soccer and rugby sides dont have the same kind of purchase on because those sports, by their very structure and the limited duration of matches, are better able to hide insecurity? Could the reason for successive World Cup failures be found in the schools system, from which all our elite cricketers come, and its associated dependence on individual heroism of the Lance Klusener variety?

Perhaps the problem is not to do with society at large but with cricket itself. It was the cricketers, after all, who failed to bowl their overs quickly enough in the opening game against the West Indies at Newlands in 2003, a failure that probably cost them the game. It was the cricketers and their support staff who failed to add a run to the Duckworth-Lewis table at Kingsmead against Sri Lanka several weeks later. It was the cricket administrators who chose to give Mickey Arthur, a plausible, convincing man who has since taken on one of the biggest jobs in the cricketing world in becoming the coach of Australia, a coaching assignment for which his limited background probably hadnt prepared him. The same could be said of Eric Simons, another relatively inexperienced man who was offered the Proteas coaching job, an offer that no one in their right mind could refuse. It is all very well blaming extraneous factors; perhaps it is the intrinsic factors the factors pertaining to the culture of cricket in this country that finally determine our lack of success.