W. W. NORTON & COMPANY NEW YORK / LONDON

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110.

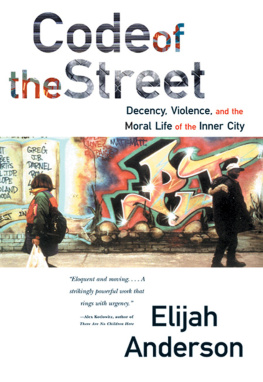

Anderson, Elijah.

Code of the street: decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city / Elijah Anderson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-393-07038-5

1. Afro-AmericansPennsylvaniaPhiladelphiaSocial conditions. 2. Afro-AmericansPennsylvaniaPhiladelphiaSocial life and customs. 3. Inner citiesPennsylvaniaPhiladelphia. 4. Philadelphia (Pa.)Social conditions. 5. Philadelphia (Pa.)Social life and customs. I. Title.

F158.9.N4A52 1999

303.3'3'0896073074811dc21

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

http://www.wwnorton.com

W.W. Norton & Company Ltd., 10 Coptic Street, London WC1A 1PU

L. C., Sr.

Leighton, Sr.

James T.

James T.

Jesse L.

J.B.

Robert Earl, Jr.

Joe, Jr.

Wilson (Junebug), Jr.

Jesse, Jr.

James T., Jr.

Robert T.

Preface

T HE present work grows out of the ethnographic work I did for my previous book, Streetwise: Race, Class, and Change in an Urban Community (1990). There I took up the issue of how two urban communitiesone black and impoverished, the other racially mixed and middle to upper middle classcoexisted in the same general area and negotiated the public spaces. Here I take up more directly the theme of interpersonal violence, particularly between and among inner-city youths. While youth violence has become a problem of national scope, involving young people of various classes and races, in this book I am concerned with why it is that so many inner-city young people are inclined to commit aggression and violence toward one another. I hope that lessons derived from this work may offer insights into the problem of youth violence more generally. The question of violence has led me to focus on the nature of public life in the inner-city ghetto, specifically its public social organization. And to address this question, I conducted field research over the past four years not only in inner-city ghetto areas but also in some of the well-to-do areas of Philadelphia.

In some of the most economically depressed and drug- and crime-ridden pockets of the city, the rules of civil law have been severely weakened, and in their stead a code of the street often holds sway. At the heart of this code is a set of prescriptions and proscriptions, or informal rules, of behavior organized around a desperate search for respect that governs public social relations, especially violence, among so many residents, particularly young men and women. Possession of respectand the credible threat of vengeanceis highly valued for shielding the ordinary person from the interpersonal violence of the street. In this social context of persistent poverty and deprivation, alienation from broader societys institutions, notably that of criminal justice, is widespread. The code of the street emerges where the influence of the police ends and personal responsibility for ones safety is felt to begin, resulting in a kind of peoples law, based on street justice. This code involves a quite primitive form of social exchange that holds would-be perpetrators accountable by promising an eye for an eye, or a certain payback for transgressions. In service to this ethic, repeated displays of nerve and heart build or reinforce a credible reputation for vengeance that works to deter aggression and disrespect, which are sources of great anxiety on the inner-city street.

In delineating these intricate issues, the book details not only a sociology of interpersonal public behavior with implications for understanding violence and teen pregnancy but also the changing roles of the inner-city grandmother and the decent daddy, the interplay of decent and street families of the neighborhood, and the tragedy of the drug culture. The story of John Turner brings many of these themes together. And the conversion of a role model concludes the book by further illustrating the intricacies of the code and its impact on everyday life.

In approaching the goal of painting an ethnographic picture of these phenomena, I engaged in participant-observation, including direct observation, and conducted in-depth interviews. Impressionistic materials were drawn from various social settings around the city, from some of the wealthiest to some of the most economically depressed, including carryouts, stop and go establishments, Laundromats, taverns, playgrounds, public schools, the Center City indoor mall known as the Gallery, jails, and public street corners. In these settings I encountered a wide variety of peopleadolescent boys and young women (some incarcerated, some not), older men, teenage mothers, grandmothers, and male and female schoolteachers, black and white, drug dealers, and common criminals. To protect the privacy and confidentiality of my subjects, names and certain details have been disguised.

My primary aim in this work is to render ethnographically the social and cultural dynamics of the interpersonal violence that is currently undermining the quality of life of too many urban neighborhoods. In this effort I address such questions as the following: How do the people of the setting perceive their situation? What assumptions do they bring to their decision making? What behavioral patterns result from these actions? What are the social implications and consequences of these behaviors? This book therefore offers an ethnographic representation of the code of the street, and its relationship to violence in a trying socioeconomic context in which family-sustaining jobs have become ever more scarce, public assistance has increasingly disappeared, racial discrimination is a fact of daily life, wider institutions have less legitimacy, legal codes are often ignored or not trusted, and frustration has been powerfully building for many residents.

A further aim of the ethnographers work is that it be as objective as possible. This is not easy or simple, since it requires researchers to try to set aside their own values and assumptions about what is and is not morally acceptablein other words, to jettison the prism through which they typically view a given situation. By definition ones own assumptions are so basic to ones perceptions that seeing their influence may be difficult, if not impossible. Ethnographic researchers, however, have been trained to look for and to recognize underlying assumptions, their own and those of their subjects, and to try to override the former and uncover the latter. In the text that follows, I have done my best to do so.