Table of Contents

IN MEMORY OF FLIP

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank my wife, Betsy, for reading every word I write, for tasting every new dish I cook, and for encouraging me to make each word and each mouthful as good as it can be. I thank Chris and Alice Canlis for their boundless support. I thank Gary Luke for seeing this book in me and encouraging me to write it. Thanks too to Lila Gault for leading me to rich sources of information about apples and cherries. And I thank Susan Derecskey for the attention she paid to each recipe. What could have been a chaotic jumble became consistent and coherent under her care.

I thank my parents for providing me with a safe home where I learned to cook, where the kitchen was never off limits, and where there was always enough to eat. I thank them especially for giving me wings to fly from that home and make one of my own in the Pacific Northwest. I am thankful that such an awesome place exists and that I am allowed to live in it.

ESSENTIAL INGREDIENTS

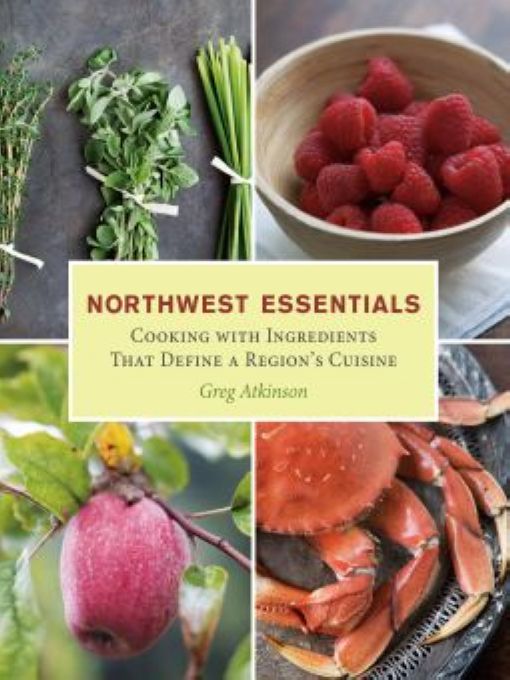

Start with the best ingredients and you cant go wrong. But what are the best ingredients and why are they the best? More often than not, the best ingredients are the ones that are grown nearby, harvested at their peak, and eaten within a reasonable distance from their source. Certainly thats true here in the Northwest. Were very fortunate. Our region is home to some of the most compelling native ingredients found anywhere in the world, and the local climate supports a wide variety of things from far away. The harvest season is long, and the yields are abundant.

The best ingredients may also be defined by a kind of alchemy that comes with familiarity. As we eat and cook with the plants and animals that thrive all around us, our own experience with these ingredients adds to their inherent value. Stopping at the same farm stand for raspberries or fresh corn first as a young couple, then with kids in the car, lends a ritual significance to the ordinary rhythm of the seasons. Visiting the same mushroom patch year after year, or fishing from the same special spot on a mountain stream, gives each years harvest a kind of poignancy, and each summers catch a kind of relevance that would never come to the one-time forager or the casual diner. Ingredients become essential when they link us to the rest of our lives.

The first time I tasted a Pacific oyster, it made me long for the oysters of my childhood, the Apalachicola oysters of the Gulf Coast where I came to know the taste of the sea. I could hardly appreciate the local oyster for what it was, because I was so keenly aware of what it wasnt. Now, after two decades of tasting Northwest oysters, I appreciate them more. Each one reminds me of a place, a time, a particular occasion. How much more local oysters mean to me now than they did when I brought that first quivering mollusk to my mouth!

Who could have known where it would lead? Dore Webb, the woman who gave me one of my first Washington oysters, owned Westcott Bay Sea Farms with her husband then, and she wanted me to try her oysters so that I would serve them in the restaurant where I had just come to work. I presented those oysters to our patrons in myriad ways: simply chilled on the half shell, steamed open and drizzled with butter sauce, grilled open, baked with savory toppings, pured into velvety bisques for a succession of Valentines Days, and for one special New Years Eve, stewed whole with saffron, cream, and flakes of 18 karat gold. Who could have guessed that Dore would visit me again in the same kitchen seven years later when she knew, but I didnt, that she was dying and that in just a few days, she would give up food altogether to die in her home by the oyster beds?

How could I have known the first time I pondered a seed catalogue with a farmer one dark January afternoon to talk about what he might grow and what I might cook the following summer that we were developing a relationship that would help nurture us both for a decade or more? Who could guess that we would sing soulful songs together in his garden, toasting our new babies with red wine and sharing his wifes sourdough bread? Who could know how I would come to miss him when the season for seed catalogues came around and I had moved away?

Even the barely edible wild roses that captured my senses the first time I saw them growing beside the freeways are so thoroughly tied now to my understanding of the changing seasons that I can read the months of the year by the condition of the rose bushes along my favorite trails. They contribute next to nothing in the way of my actual food, those roses. But the rose-petal jellies and rose-scented teas I occasionally enjoy, and often think about, keep me grounded on the great wheel of time, even as the years spin uncontrollably by.

Berries, mushrooms, leafy greens, sacks of potatoes, and the bounty of the sea are more than just food, they are vital links to the elements that formed them and to the people who grew and gathered them. A cornmeal-crusted trout sizzling in bacon fat connects a happy camper to the lake and the water that tastes like the stones from which it sprang. A beet pulled shaking with dirt from the garden is a bridge to the very earth that bore it. The foods that thrive here in the Northwest are more than items on a list of ingredients, they are points of departure; they are almost, but not quite, the raison dtre for the recipes they inspire. But of course producing something good to eat is the real purpose of any recipe. And linking a collection of recipes to the people and the places that inspired them is reason enough, I hope, for a collection like this one.

I have never been able to accept that old analogy of man as machine and food as fuel. In the great scheme of things, I imagine that we are not machines at all, but we are something between animals and angels, and food is the golden chain that keeps us connected to both worlds. To the degree that we devour it unthinkingly, we are like the former, and to the degree that we celebrate it with understanding and gratitude, we are like the latter.

SELECTING THE ESSENTIALS

In the chapters that follow, I hope to share some insights into the foods that have shaped my understanding of Northwest cooking. The selection of ingredients is not arbitrary, but it is subjective. When in the course of researching and writing this book I asked people what they considered the essential ingredients of Northwest cooking, they quickly volunteered apples and salmon. Then after a pause, a few added berries, oysters, or mushrooms. Some people seemed surprised that I found eleven ingredients that warranted inclusion.

I might have included more ingredients than I did. I thought of adding a chapter on wheat; Washington grows a huge proportion of the nations winter wheat, but wheat is not unique to the Northwest, nor do we use it in ways that are peculiar to the region. Besides, wheat and its myriad uses constitute a book in their own right. I think Northwest vegetables are exceptional, but like wheat, the subject is too vast and too universal to be confined to one of these chapters

A couple of ingredients intrigued me, and I came close to including them. Rhubarb, for instance, is produced almost exclusively in the Northwest. We grow over 90 percent of the nations commercial rhubarb crop, but even if we grew 100 percent, it would hardly provide enough material to warrant a chapter of its own. Pears, too, are closely associated with the Northwest; in fact, the vast majority of the nations commercial pear crop is harvested here. But pears, at least to my mind, are best enjoyed more or less unadulterated. So I have afforded them a brief discussion and a few indispensable recipes in the chapter on apples, to which they are closely related.