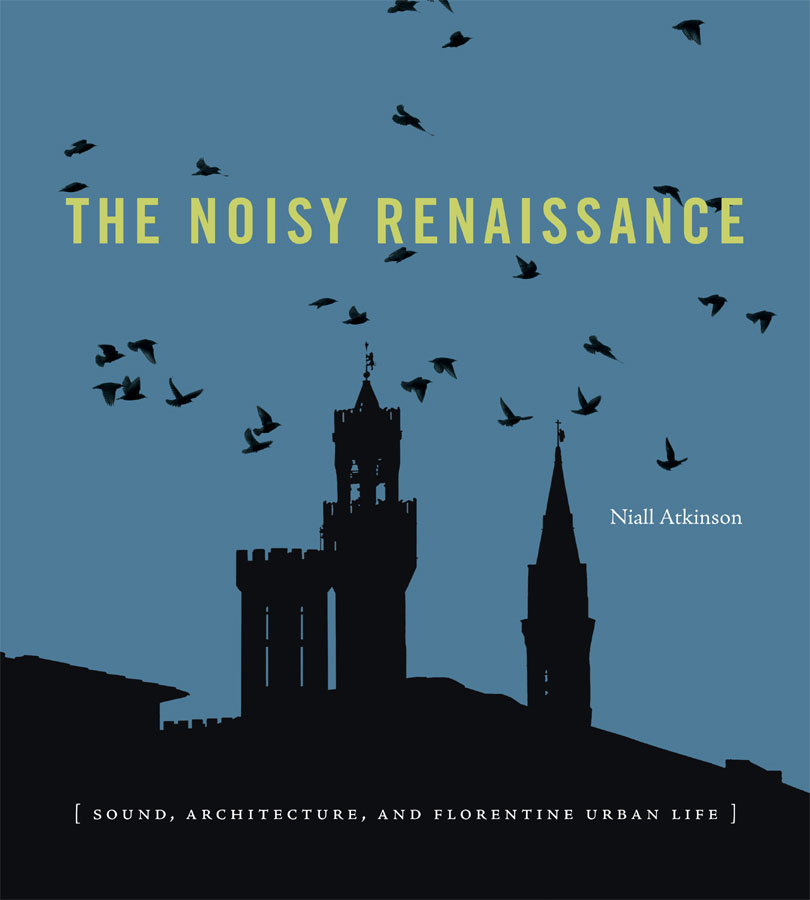

THE NOISY RENAISSANCE

Portions of this book were previously published as The Republic of Sound: Listening to Florence at the Threshold of the Renaissance, I Tatti Studies in the Renaissance 16, nos. 1/2, 2013), and Sonic Armatures: Constructing an Acoustic Regime in Renaissance Florence, Senses and Society 7, no. 1 (2012).

THIS BOOK IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A COLLABORATIVE GRANT FROM THE ANDREW W. MELLON FOUNDATION.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Atkinson, Niall, 1967, author.

Title: The noisy Renaissance : sound, architecture, and Florentine urban life / Niall Atkinson.

Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Analyzes how the premodern city, through the example of Renaissance Florence, can be understood as an acoustic phenomenon. Explores how city sounds, such as the ringing of church bells, can be foundational elements in the creation and maintenance of urban communities and the spaces they inhabitProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015050853 | ISBN 9780271071190 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH : Architecture, RenaissanceItalyFlorence. | RenaissanceItalyFlorence. | City soundsItalyFlorenceHistory. | BellsItalyFlorenceHistory. | Architectural acousticsHistory.

Classification: LCC NA1121.F7 A85 2016 | DDC 724 / .120945511 DC 23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015050853

Copyright 2016

The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Printed in the Czech Republic

Published by

The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA 16802-1003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI Z 39.481992.

CONTENTS

Authorship, that most central, perplexing, and vexed issue confronting art and architectural historians, haunts the imagination of the Italian Renaissance scholar with particular intensity. But even in an age often defined by towering proper names, not even Michelangelo could hide the army of experts and collaborators necessary for the successful completion of his most ambitious works. Although only my name is printed on the cover of this book, many other proper names occupy the numerous stops along this journey through the sounds of Florence, where I can now reflect upon how paradoxically collaborative such a seemingly individual task writing turns out to be.

My gratitude must begin with the three people who guided my research from the beginning and who laid the conceptual foundations of this study. John Najemy and Marilyn Migiel are two of the subtlest thinkers and interpreters of Renaissance texts that I have had the fortune to encounter. But singular gratitude must go to Medina Lasansky, whose reconceptualization of what architectural history can be, what it can do, and why it matters remains the intellectual basis through which I think about the past. I also want to thank Sheryl Reiss, who, with an open academic generosity, became an early mentor and supporter. I will always remember my happiest days at Cornell spent with my cohort of historians, all of whom continued to inspire me beyond the campus: Alizah Holstein, Sophus Reinert, Ionut Epurescu-Pascovici, and Robert Fredona. Bob, in particular, has been both a critical resource and sensitive interlocutor of all things Florentine all along this journey.

There are too many people to thank in Florence, but I want to name the most important. I remember lunch with Lawrin Armstrong, where the conspiracy of bells was truly born. Gerhard Wolf read and commented very helpfully on my early writing, and he also opened up a new and innovative world of scholarship as the director of the Kunsthistorisches InstitutMax-Planck-Institut, with a newly conceived vision of art-historical research. That vision was complemented by the arrival of Alessandro Nova, who took a chance on a young scholar and welcomed me into a new research project, Piazza e monumento, that fundamentally refined the direction this research was to take. I will always be grateful to him for the seminars he led with our team in his office. Many others at the KHI were instrumental in my Florentine education, helping me read, translate, and understand difficult texts, find books, interpret sources, gain access to sites, and offer me invaluable critique: Benjamin Paul, Ester Fasino, Rebecca Mueller, Philine Helas, Urte Krass, Monika Butzek, Ortensia Martinez, Alberto Saviello, Marco Campigli, Michelina de Cesari, Hannah Baader, Lia Markey, Katie Poole, Lisa Hanstein, Manuela di Giorgi, Henrike Haug, Peter Scholz, Sabine Feser, Andre Worm, Anna Rogasch, Hana Grndler, Jan Simane, Oliver Becker, and Christine Ungruh. The Piazza e monumento members: Cornelia Joechner, Stephanie Hanke, Frithjof Schwartz, Brigitte Soelch, Sophie Huggler, and Elmar Kossel.

When I began to present the findings of my research, I found a community of Italianists whose intellectual curiosity, generosity of spirit, openness, and general good humor sealed my deep affection for a field that continues to generate vigorous intellectual debates, just as it did centuries ago. But in particular, there were those who continued to engage with my work, exchange ideas, offer advice, share material, invite me to lunch or aperitivo, all of which inspired me to move in new directions: lifelong friends and colleagues, such as Patrick Baker, Babette Bohn, Luca Boschetto, Charles Burroughs, Meghan Callaghan, Catherine Carver, Douglas Dow, Nicholas Eckstein, Richard Goldthwaite, Richard Ingersoll, Fabian Jonietz, Dale Kent, Anne Leader, Alick McLean, M. Michle Mulchahey, Jonathan Nelson, Nerida Newbigin, John Paoletti, Linda Pellecchia, Brenda Preyer, David Rosenthal, Patricia Rucidlo, Sharon Strocchia, Nicholas Terpstra, Martino Traxler, and Saundra Weddle. All of them have left a lasting imprint on the content of this book, and it is there that I can remember them all.

I would like to separate several persons from the above list because they belonged to a series of remarkable conferences and workshops held at the Courtauld Institute between 2009 and 2012, where many of the core narratives and methodological structures of this book were developed. Street Life and Street Culture: Between Early Modern Europe and the Present served as an intellectual incubator and brought me into close involvement and sustained dialogue with a remarkable set of scholars for whom I have a deep admiration and owe an intellectual debt, and whose work has a deep affinity with my own: Georgia Clarke, Fabrizio Nevola, David Rosenthal, Stephen Milner, Guido Rebecchini, and Rosa Salzberg.

Of the many Florentine institutions that scholars rely on in Florence, I must thank the staff of the Biblioteca Laurenziana, the Biblioteca Riccardiana, the BNCF, and the Archivio di Stato. I would like to personally thank Emilio Penella of the Archivio di Santa Maria Novella, Margaret Haines of the Opera del Duomo, and Joseph Connors, who, as director of the Harvard Center at Villa I Tatti, was an early supporter and intellectual model and who gave me a copy of the Bonsignori map of Florence, which I use obsessively throughout this book.