This publication has been supported by a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts

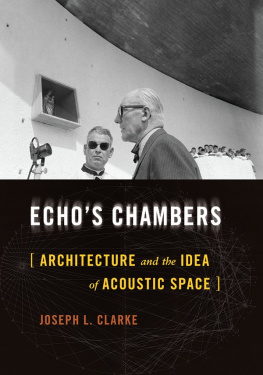

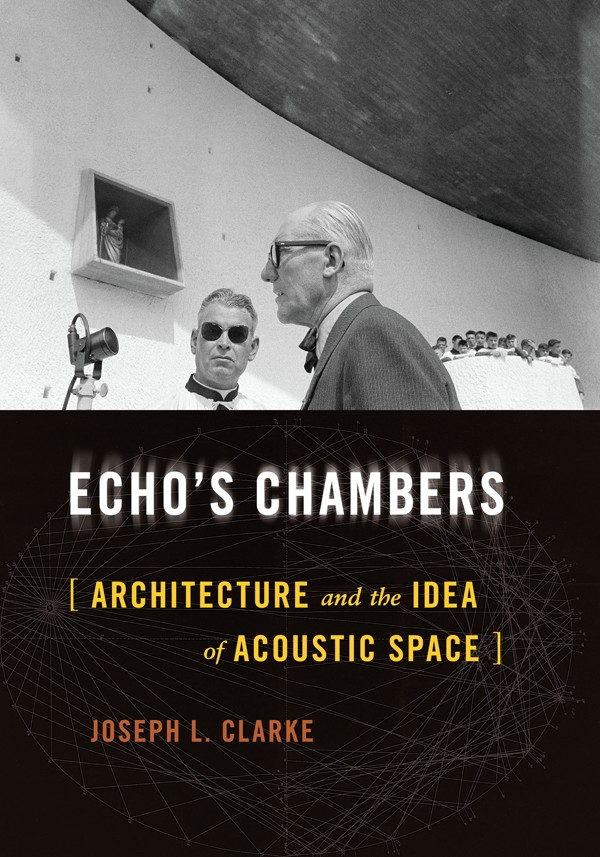

COVER ART: Le Corbusier speaks at the consecration of Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp, France, June 25, 1955. Next to him is Father Arthur Bourdin, the chaplain at the time. Ren Burri / Magnum Photos.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I WILL ALWAYS BE INDEBTED TO THE MENTORS WHO HELPED FORM MY understanding of architecture. In particular, my first teacher, Aarati Kanekar, kindled my fascination with buildings that present paradoxes. Peter Eisenman taught me that the questions a building raises are more interesting than the problems it purports to solve. Robert A. M. Stern taught me that at parties, I should not talk to the same people all the time. Kurt W. Forster was especially pivotal in shaping my thinking about architecture and sound. His generous and erudite conversation frequently induced an uncanny intellectual resonance, in which ideas that one moment seemed as piecemeal as inert grains of sand suddenly coalesced into unexpected figures.

This book has also benefited immensely from the questions, conversation, and encouragement of Michelle Addington, Zeynep elik Alexander, Christy Anderson, Manon Asselin, Niall Atkinson, Mark Bailey, Tim Barringer, Barry Bergdoll, Mario Carpo, J. D. Connor, Peter Drobac, Kyle Dugdale, Kevin and Elaine Harrington, William Hood, Brian Kane, Ethan Matt Kavaler, Carl Knappett, Gundula Kreuzer, Henrike C. Lange, Sherry Lee, Elizabeth Legge, Inga Leonova, Ryan Lobello, Stanislaus von Moos, Maud Newton, Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen, John Durham Peters, Emmanuel Petit, Michelangelo Sabatino, Haun Saussy, Daniel Sherer, Brigitte Shim, Viktoria Tkaczyk, Jan Claas van Treeck, and Christopher Wood.

An especially formative event for my thinking was an interdisciplinary symposium, The Sound of Architecture, that Kurt Forster and I convened at the Yale School of Architecture. I am grateful to all the symposium participants, as well as the school and its staff. I am also indebted to more conference organizers and audiences, journal editors, and peer reviewers than I can name but especially to the editors of Grey Room for inviting me to be the guest editor of a special issue on acoustic modernity. MIT Press kindly allowed me to draw on an essay from that volume for the Fine Arts, the J. M. Kaplan Fund, the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the University of Toronto, and Yale University.

I also express sincere gratitude to the librarians and archivists who helped me access and study the materials examined in the book; to Eric Dugdale, Karl-Magnus Gustave Brose, and Marina Dumont-Gauthier for help translating difficult passages; and to Alexa Breininger for assistance with the bibliography. Abby Colliers editorial guidance was instrumental as the book assumed its final form. I thank my students as well, for their insights, probing questions, and good humor.

Most important has been my family. My mother taught me to read, to travel, and to create. My two brothers opened my ears. Jordan Bear not only advised me unfailingly but came along on a journey that led us into caves and up mountains. Finally, my father showed me what it is to be a conscientious and broadly liberal intellectual. I dedicate this book to him.

NOTE ON TRANSLATIONS

ALL TRANSLATIONS ARE BY THE AUTHOR UNLESS OTHERWISE SPECIFIED. Italicized words in quotations always reflect emphasis in the original sources.

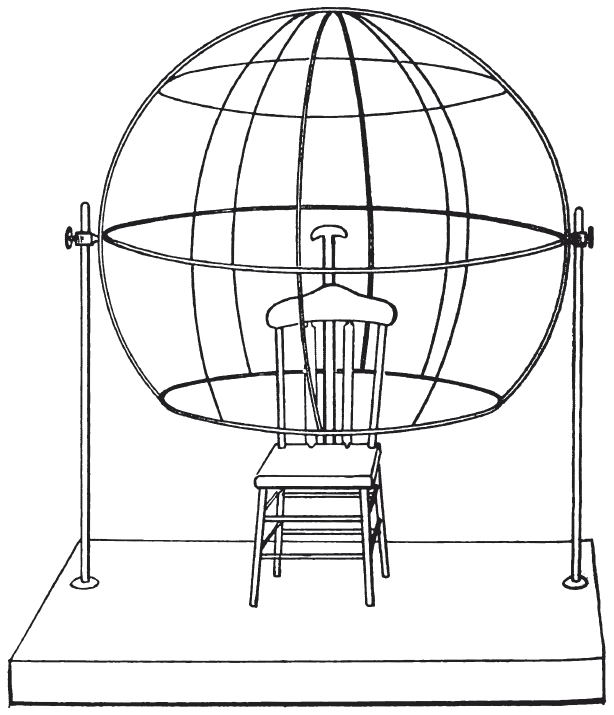

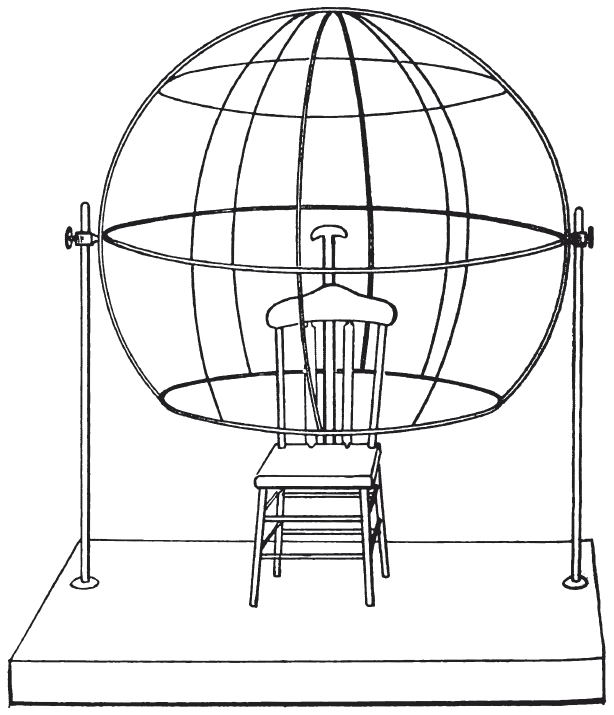

I.1. Acoustic "cage" for conducting psychophysiological experiments on sound perception. The subject would sit in the chair with eyes closed and attempt to identify the location of sounds produced at various arbitrary points on the surrounding spherical wireframe. Illustration from Matataro Matsumoto, "Researches on Acoustic Space" (1897).

INTRODUCTION

THE NIGHT SHALL BE FILLED WITH MUSIC

UNTIL RELATIVELY RECENTLY, THE MOST SOPHISTICATED SONIC MEDIA were buildings. The acoustic properties of a building can facilitate or frustrate the activity it houses, whether conversation, artistic performance, or ritual. A room may seem monumental or intimate depending on its level of reverberation. Architecture often contains secret places where sounds echo or voices carry in surprising ways. All these acoustic conditions can have political consequences, determining whose words are heard and by whom. Sound matters not just in specialized buildings such as auditoria and concert halls but in almost every kind of structure. Yet the discourse of architecture often struggles to engage critically with the sonic life of buildings. Presented in arid scientific terms, acoustics can seem peripheral to the disciplines core concerns.

This book offers an architectural history of architectural acoustics, positioning it as a central problem for the field. It also argues that the elaboration of architectural acoustics helped provide modern culture with words, representational conventions, and intellectual frameworks for conceiving sound spatially. After all, sound takes place. To hear a sound is, with few exceptions, to perceive its arrival from somewhere. While humans ability to recognize locational cues in sound is a biological faculty based in the auditory cortex, how one interprets these cues is culturally determinedbound up with social and linguistic practices, habits of mind and body, sensoryhierarchies, artistic forms, communication technologies, even religious commitments. It is connected in especially significant ways with architecture.

In recent years, the most important social and cultural accounts of sound in the physical environment have drawn on the idea of acoustic space. This locution and related terms such as soundscape have appeared more and more frequently in writing about architecture, not to mention scholarship in media and communication studies, musicology, literary studies, anthropology, and art history. Yet acoustic space elides several distinct meanings. It is sometimes posited as inherent in the physical makeup of a building, as when architectural historians judge a Venetian church to be an unpromising acoustic space because its walls reflect an extreme amount of sound, garbling the singing. Others take acoustic space to be a figment of the human perceptual apparatus, a mental map of ones surroundings constructed on the basis of what one hears, as when a writer describes how he gradually became attuned to acoustic space after going blind, or when a media scholar argues that nineteenth-century sound technologies prompted a reconstruction of the shape of acoustic space. For still others, acoustic space is better understood as a kind of social infrastructure, a collective framework for interacting with other members of a group through the making and hearing of sound: this is the intended meaning when an ethnomusicologist writes that the medium of radio provides its dispersed audience with a shared acoustic space.