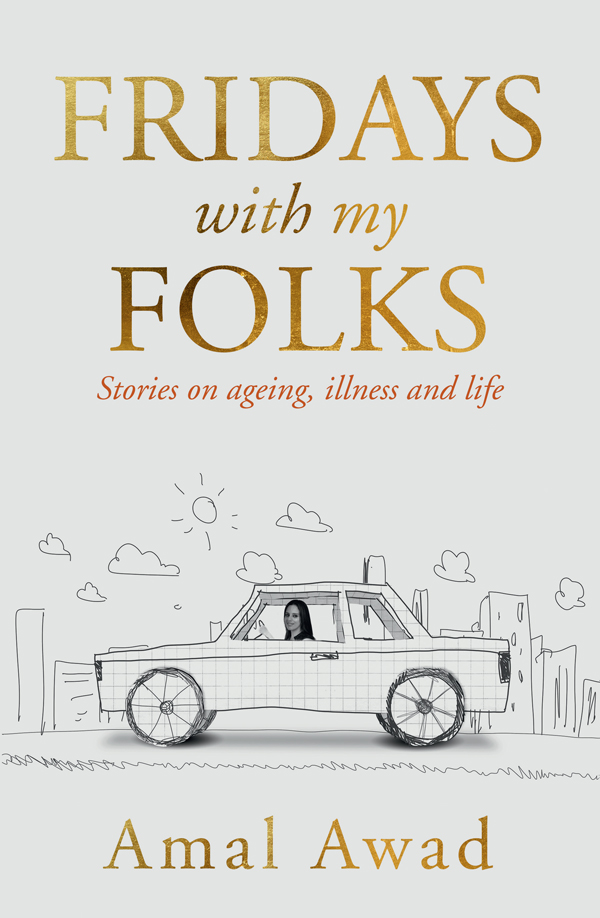

About the Book

Amal Awads life changed forever when her father was diagnosed with kidney failure. It was a shock to see the impact it had on him, both physically and mentally, and the way the side effects trickled on to those around him. Work had always made him feel whole, and retirement was a challenge.

On a mission to help her father and support her mother, Amal began spending Friday with her parents. She saw the gaps in discussion around age and illness. Amals personal experiences prompted her to explore how Australians are ageing, how illness affects the afflicted and those around them, and what solutions exist when hope seems lost.

So many people are similarly navigating a new reality weeks dotted with doctor appointments; conversations that deplete and reveal at the same time; reshaped family relationships. Amal speaks with doctors, nurses, an aged care psychologist, specialists, politicians, ageing people living alone and others in a retirement village, to gain insights and to consider solutions.

At a time when ageism and health are high on the publics radar, what were not always talking about is how to deal with the anxiety, depression and overall challenges that come with someone you love facing their mortality as their health declines.

Fridays with My Folks shares heartfelt, honest stories that will help others who are in similar positions. People who are having to reorientate themselves when the boat has taken a battering and they have to take a new direction.

This book stems from personal experiences, but it expands to a far more universal discussion about life, suffering and hope.

Too long.

Too familiar with mountains.

Joy has been a habit.

This rain.

PROLOGUE

I will write the truth gently.

Since I was a girl, I have admired the wedding photo that hangs on my parents bedroom wall. It has a surreal quality to it. Its not black and white; rather, its been colourised in a way that makes it look more like a hyper-colour painting. My mothers almond-shaped eyes, lined in black kohl, are the first thing you notice. But then, to the side, is my father, handsome and impossibly young, embracing her, beaming with pride.

My mother looks glamorous, mature for her age and experience, and my father also captivates. Bright eyes, optimism and strength. Thats how I have always known him. Somehow invincible, even if he was a remote figure. He wasnt demonstrative when I was growing up; he was matter of fact and deeply immersed in work.

I stare at the wedding photo with fresh eyes now, because in 2013 my father was diagnosed with kidney failure.

I was in my mid-thirties, in the process of immense personal change, when my world was turned upside down. Not just my world that of my entire family. We quickly saw that life would evolve into a new reality. A schedule for my father filled with appointments rather than retirement luxuries. My brothers and I never without our phones in sight. Every year since has seen a longer visit to the hospital, always unexpected, a shattering of the peaceful revised norm.

It does something to you. As resilient as I am, even I had to concede at one point that my emotions, turbulent and overwhelming, were a caution. But we are not alone. During one hospital visit for my father I found myself reaching out to friends, something I have always struggled with asking for support, privately asking them to pray for my dad, for the whole family. I asked for positive vibes, healing love in any form to be telegraphed towards us.

These were friends who themselves were navigating painful, disrupted realities, so I knew they would understand. Eventually, as we discussed the ins and outs of hospital visits, the time we put aside for our parents, I realised how many of us were experiencing similar issues. We half-jokingly compared schedules. Three appointments next week for Patty and her dad. Marcela has one. Lucky. Acquaintances, colleagues, strangers they had their stories too, and they shared them easily, relieved to be unloading an experience that had felt isolating as though they were speaking a language not everyone can understand. We were immediately connected. An ageing parent, someone we love not in perfect health the war stories were fierce, painful. Maybe sharing them was not only connection but also a way of normalising things. The commonality helped. Friends helped. So did the therapist I finally acknowledged I must see, because life felt full, overwhelmingly so at times, and I realised how important it was to talk about things. To express fear so that it lost power rather than consumed me.

There were dark moments, but I was strangely calm. Tired, probably overdosing on caffeine. But I was present, the daughter I needed to be for my father, and for my mother, Dads constant companion.

For a time I retreated into my usual interests and stayed busy with work. Strangely, the activity that helped me best decompress was doing puzzles, usually a thousand pieces, which I put together while a TV show played in the background. Its the therapy of them. Knowing that concentrated purpose and persistence pay off; that sliver of relief you feel each time you lock a piece into place. I wondered if there was a metaphor in my puzzles: it will all come together. Persistence that yields the desired results.

Still, I was asking myself, how do we transform ourselves from children to people who care for a parent in a similar fashion as they cared for us?

Although there are many books on ageing, its only when you are experiencing it for yourself, or with a close family member or friend, that you realise how painful and life-changing it is. Moreover, you come to understand how universal the story is: no matter how our winding paths vary or converge we are all born and one day we will all die; and fears around death and illness tend to be universal.

As a writer and observer, I was naturally driven to record some of the stories my friends, and strangers, were sharing with me, to make sense of what was unfolding in my familys life; and also to pull away the veils of mystery that surround ageing, and cause the anxiety that marbles into fear. There is pain and stigma associated with sickness and our bodies getting older, and they are experienced not just by the elderly. I felt strongly that it was time we all talked more about this and listened to others stories.

Fridays

I often think back to my fathers reaction to his diagnosis of kidney failure. Im going to stay hopeful, he told me. And his positivity worked until he had to face the limitations of his body as it deteriorated. He was still driving, but less so. Still active, but things like getting to the mosque on a Friday became more difficult.

I needed to see my parents more often, to take them places that would be harder to get to themselves. In a moment of inspiration I committed every Friday to them. I wanted them to have as much normality to hold on to as possible. I needed to ensure Dad could get to the mosque, and sit in the company of other men in worship as he had always done. I wanted to be beside my mother, accompany her in the process of a changing lifestyle.