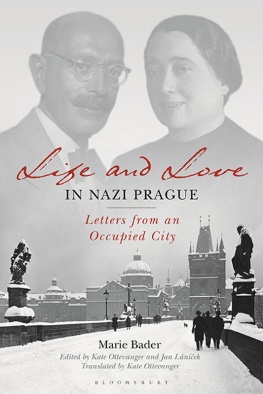

Life and Love

in Nazi Prague

Life and Love

in Nazi Prague

Letters from an Occupied City

Marie Bader

Translated by Kate Ottevanger

Edited by Kate Ottevanger

and Jan Lnek

Dedicated to

Marie and Ernst

Edith and Grete

In a letter written by a relative who survived, appended to this collection, the author writes that Our children are grown up now and the hard school of Auschwitz taught them a lot. You can be sure that everybody who came out of Auschwitz did learn how to fight in life. The protagonist of this moving and powerfully engaging book, Marie Bader, did not survive. But her letters constitute not only an important source on life in Nazi-occupied Prague but an exemplary case study of how Jews during the Holocaust struggled to maintain their sense of self in the face of increasing persecution.

Dan Stone, Royal Holloway

University of London

Marie Baders letters offer a captivating, if poignantly tragic, glimpse into the life of Jews in Nazi-occupied Prague. Neither she, nor her beloved addressee in Greece, survived the war, but we are fortunate today to be able to read her remarkably vibrant and strikingly perceptive efforts to describe to him her hopes and fears as she negotiated with verve, and even humour, anti-semitic repression and the impending threat of deportation. Thanks to the especially skilful editing and scholarly annotation of her letters, general readers, students and experts alike will find much here that is thought-provoking and will have great difficulty putting the book aside.

Benjamin Frommer

Associate Professor of History, Northwestern University

O h my treasure, do you know how I long for the smell of a wood, for the smell of fresh air?

So wrote Marie Bader from her tiny flat in the Karln district of Prague on 25 September 1941. Her letter was one of 154 written between the autumn of 1940 and April 1942.

Their recipient was Ernst Lwy, Maries second cousin, with whom an intense love affair was developing, albeit one separated by hundreds of miles. Ernst was living in similarly restricted circumstances, but in the very different environment of Thessaloniki in northern Greece.

Ernst and Marie had known each other from childhood, but it was only with the deaths of both their spouses that a mutual strong attraction noticed previously and frowned upon by their respective families was finally able to develop and thrive.

Both were severely restricted in their freedom of movement, and, though willing to risk the little stability each enjoyed, were unable to achieve the reunion and stable life together that both hoped for, so that the love affair developed in words on paper.

This volume of letters gives an insight not just into this story of late-flowering desire Marie was fifty-four at the time the letters begin but also into the anxiety and uncertainty felt by Jewish people at that time, when families were so often dispersed to different parts of the world and the future for those still in Europe was so unsure.

The correspondence has a special connection with the Imperial War Museum, since Jeremy Ottevanger, Marie Baders great-grandson, who discovered the letters in his parents attic, is a close colleague. It was my privilege to meet with Jeremys parents, Kate and Tim, to discuss the book in its early stages, and it was a special pleasure to see the project grow from an idea to a full publication.

Kate Ottevanger undertook the considerable task of translating and editing the letters, and writing a highly informative introduction. It cannot have been easy to work out the details of a complex set of family relationships, and how the shifting events of the Second World War impacted on all of Maries relatives and acquaintances, but this Kate Ottevanger has achieved with consummate skill. Her Afterword in which she describes further groups of letters to and from her grandmother and probes the impact that the unravelling of her grandmothers last two years has had on her and her family is exceptional for its depth and insight into our understanding of exile, loss and identity.

In Jan Lnek, moreover, Kate found a co-editor of considerable ability who, as well as adding a valuable historical perspective, has provided a well-researched post-script, explaining the likely fate of Marie Bader. To work on a project of this kind must have been a challenge and to have the perspective of a well-networked expert from the country of Marie Baders birth was fortunate indeed.

I know from my past work with the Holocaust Exhibition here, how rare it is for letters to survive from that period but in particular full sets of correspondence. This volume will be of value to historians, scholars of literature and the general reader, for the detail it provides on wartime Jewish life in Prague, in particular how different elements in the population responded to the Jews under threat, and for the particular optimism, thoughtfulness and insight of one woman who endured that terrible time.

Suzanne Bardgett

Head of Research and Academic Partnerships

Imperial War Museum, London

M y thanks go first to Erika Kounio Amariglio who, after initial hesitation, generously agreed that our grandparents love story should be made public. Without her blessing I would have struggled with my conscience. Her daughter, Theresa Sundt, has kindly provided me with family photos. Suzanne Bardgett of the Imperial War Museum, through her enthusiasm and her belief in the importance of the letters, encouraged me to cross that bridge of conscience and I am most grateful for this. Sir Martin and Esther Gilbert were also among the first to appreciate the significance of this collection. I must thank, too, Chris Szejnmann of Loughborough University for his support and in particular for putting me in touch with Jan Lnek, without whose wide knowledge of their historical context these letters would have been so much less meaningful.

Thanks, too, to family and friends you know who you are! who have backed this venture through all its stages. I am especially indebted to my husband Tim for his constant assistance and for his relentless detective work which helped broaden our knowledge of so many of the characters who appear in the letters. And last, but certainly not least, I would like to thank our son Jeremy for discovering the letters in the first place.

Kate Ottevanger

November 2018

The discovery

In October 2008, we made a remarkable discovery. Rummaging about in the attic, our son Jeremy opened an old suitcase which had been there for over ten years, ever since I cleared my aunt Gretes house in Sheffield, following her move into a nursing home. In the suitcase were several items of photographic equipment including an old camera, glass photographic plates and negatives. Always interested in old objects, he pulled them out to examine them further and saw underneath a package, wrapped in brown paper, on which was written, in Gretes hand, Read some of these, 18/5/53. Removing the brown paper we found a further wrapping, pale blue this time, on which was written in pencil: Briefe von Marie Bader, entweder vernichten oder durch Edmund Benisch, New York, Bay Shore, 81 Brook Aven. an Maries Kinder senden. Benisch ist Cousin von Marie

Next page