To my brother,

To my sisters.

Contents

Chronicles of her appearances

What need could I have of a water clock

we have long measured the years in tears;

to invite an angel home would be a marvellous thing,

but it would be unbearable if the angel were to invite us.

Vladimir Holan

1

She entered the book. She entered the pages of the book as a vagrant steals into an empty house, or a deserted garden.

She entered suddenly. But she had been circling the book for years. She would brush against it though it did not yet exist she would leaf through its unwritten pages, and some days she even made its blank, expectant pages rustle faintly.

The taste of ink would rise beneath her step.

* * *

She slipped into the book. She edged into the pages as a dream visits a sleeper, unfurling within his sleep.

She may go anywhere and everywhere, gaining entrance wherever she chooses; she sails through walls as easily as through tree-trunks or the piers of bridges. No material is an obstacle for her, neither stones, nor iron, nor wood, nor steel can impede her progress or hold back her step. For her, all matter has the fluidity of water.

She walks straight ahead without ever turning back. Her movements seem dictated by sudden secret needs, and her sense of direction is quite baffling. She may stand stock still in the middle of an empty street, or cut across without apparent reason, having perceived a sound inaudible to any other ear: the beating of a heart heavy with too much loneliness, or pain, or fear, somewhere in a room, a kitchen or a passing tram.

Often it is a human heart long dead that has attracted and diverted her. She moves among the dead as much as among the living, her hearing perceives the slightest breath, the furthest echo.

The colour of ink, endlessly dried and then fresh again, has always glistened in her wake.

* * *

She swept into this book. That is how she always proceeds: like the wind.

She looms up without warning, at times and places where she is least expected. Then she claims the attention of all, making her way heedless of the astonishment she causes, the alarm she arouses. Perhaps she is unaware she has been seen.

She goes her way and never turns around. But none could say where that path is leading, what compels her steps, what drives her so. She passes like a stray dog, a vagrant, like dead leaves carried by the wind.

The wind the wind of ink rises at her passing and blows beneath her step.

Made purely of her footsteps, this book too proceeds by chance.

2

But what is chance? It is confused sometimes with luck, sometimes with ill-luck; ideas of risk, of doubt, of danger and of venture are connected to it. The notion of chance is fluid and evasive, one must be careful with it.

The chance which prevails at the manifestations of this strange wanderer, which guides her steps as she sweeps through bricks and mortar, has nothing of the fortuitous about it, still less anything of the random. This wandering woman has such gravitas, such patience and endurance in her roaming, and there is such power in her fleeting appearances.

For when she does appear, she fills the space of all the visible, compelling attention from all eyes, from all senses, sowing alarm in peoples hearts.

* * *

Indeed, it is only the writing of this text which gropes and fumbles, which tacks aimlessly for lack of any sense of a whole, of any certain landmark. Yet how can one chart the movements of an unknown woman who appears in the realm of the visible only intermittently?

The wind of ink which blows in her footsteps makes the words bend and bow, it drags up images which had been sunk in memory at the very limits of forgetfulness, and it leafs in anticipation through the pages of the book which cannot but be fragmentary, and unfinished.

3

Who is this unknown woman?

A vision, herself a bearer and sower of visions.

A vision niggardly with her appearances, which have been rare, and always very brief. But each time her presence was intense.

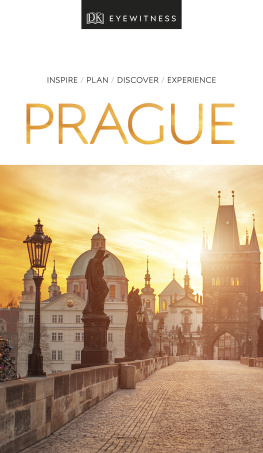

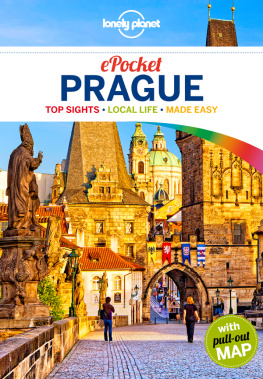

A vision linked to a place, emanating from the stones of a city. Her city Prague. She has never appeared anywhere else, though it is certainly within her power to do so.

* * *

This woman has neither name, nor age, nor face. Or if she has, she keeps them hidden.

Her body is majestic, and disturbing. She is immense, a giantess; and she has a strong limp. Her left leg is much shorter than her right. She lifts her feet with effort as though they were immensely heavy, but she treads with even greater effort, as though, once in contact with the ground, they suddenly became extremely vulnerable.

Her clothes are simple, badly cut and of coarse cloth. Her massive, awkward frame is bundled rather than clothed in its lengths of hessian, or hemp. It is as though she had hacked her thigh-length cloak from some bit of tarpaulin tugged from some piece of scaffolding.

There is so much scaffolding running along the house-fronts; the stanchions are rusting, grass grows at their base. Some alleyways are entirely roofed in under these rough structures of corroded metal and mouldering wood.

Light is barred from them; shadow stagnates under the gangplanks, seems to drift there, gradually to solidify. Birds roost on the crosspieces with their ill-fitting battens, amidst the debris of masonry or plaster fallen from the pediments of the houses.

Her long dress is of sackcloth. The shadows of its folds are darkest brown. But its weave is so bare that anything may catch upon it; the hem is fraying and trails over the paving stones, matted with dust and mud.

The woman has no care for how she looks.

She is like those whose hearts have been laid too bare and left too long uncomforted. Nothing can any longer clothe those whose hearts lie in darkness, whose thoughts catch as they walk deserted streets.

* * *

Although she is huge and cumbersome, and limps badly, this woman makes no noise as she walks.

Her steps are silent, but her body whispers like the wind: as though some small gust were caught in the folds of her garment, a faint whisper of ink; or is it tears?

Chronicles of her appearances

Who is pacing up and down at the threshold,

whose steps are those which murmur in my soul,

whose approaching solitude do they foretell,

who come here, who am I questioning?

I see no one.

Bohuslav Reynek

The first time she appeared was on an autumn evening, in an alleyway in the old town. A fine rain was falling. The bitter smell of must and rotten wood from the old scaffolding, abandoned along the houses, mingled with the smell of the fog.

In Prague, from the end of autumn and throughout the winter, the mist has a smell, and even a texture. Some evenings it is almost palpable, it is so thick and yellowish. The smoke from the city swells and colours the mist, the lignite dust floats in the air with a bitter-sweet taste. Cities, like bodies, have their smell, their skin.

The giant-woman was limping down the alley, haloed with blue-green light. Had she just come out from a portecochre masked by the scaffolding? Her head, wrapped in an off-white linen shawl, brushed up against the first level of the walkways. A wide brown hood hung from the nape of her neck. Her head was high.

She always holds her head high.

It seemed as though she must knock into the uprights which supported the walkways, already all askew; that she was about to send them tumbling down; she rolled so as she walked, and her shoulders were so broad. But she scarcely touched the slender stanchions. The pitch of her great body is always very gentle.

Next page