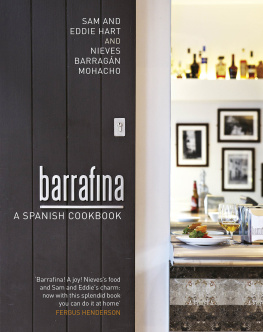

FIG TREE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Fig Tree is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2017

Copyright Nieves Barragn Mohacho, 2017

Photography copyright Chris Terry, 2017

Illustration copyright Gill Heeley, 2017

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-241-97879-5

To my parents

Maria Nieves Mohacho and Pedro Barragn

INTRODUCTION

I come from a family that loves home cooking. Growing up in Santurtzi (Santurce) on the coast near Bilbao, an area famous for its sardines, we would occasionally go out to bars at the weekends, but pintxos (what we call tapas in Basque) are expensive and you dont feel as satisfied or full as when you sit down to eat a proper home-cooked meal. Coming home from school or work for lunch, wed sit down at the table and start to talk about what we were going to have for dinner. When we sat down to dinner, wed start to talk about what we were going to eat tomorrow for lunch. It was always all about food, food, food.

My mum loved running her house and a big part of that was making sure that her family all ate well. Of course, its fairly normal for your mum (or maybe your dad) to make lunch and dinner, but for my mother it was about getting the best ingredients and products. They didnt have to be expensive, it was just about selecting them with care. Thats what I do in my cooking now: its all about ingredients and products and finding the very best, whether its a leek or a tomato. Selecting your ingredients with care is a very Spanish thing. As a child, when I went shopping with my mum on Saturday mornings, she would always say things like, Can I have this peach? No, not that one, that ones a little bit bruised, can I have that one? Or, if we were at the fishmongers, choosing red mullet, she would look at the fishes eyes and see the one that wasnt so fresh and say, No, dont give me that one! She taught me to be very picky.

When I came home from school, my mum would start to make the dinner and make up a game to keep me entertained. Id see her preparing things, and shed say, Lets do this, so Id pick the parsley, or pod the peas or broad beans fun jobs that werent dangerous. Every time my mum tasted what she was cooking, she would give me some too. Thats probably why Ive never been scared to try anything, because thats what my mum taught me. In our house it was normal to eat livers, brains and sweetbreads.

). Plus salad and maybe a little jamn, and always bread. No one would really speak during the first course except to say, Pass me the bread because we were all hungry. But by the second course we would start talking and asking about each others days and, of course, my mum would ask everyone what they wanted to do for lunch tomorrow

Even when I was in my late teens and going out at the weekends, I was always thinking about eating well. I loved going to a particular restaurant where they served Galician-style octopus on potatoes: it was tapas, and you were eating standing up, but it was a great way to start the evening. I didnt want to eat half a sandwich or a burger that was for the end of the night. I spent all my money on food and restaurants. I still do.

I never thought I was going to be a chef. My mum used to say that she loved cooking but being a chef was different. Now, of course, its fashionable: you just have to turn on the TV to see the dozens of cooking shows.

I wasnt sure what I wanted to do: I volunteered in the Red Cross because I liked caring for people, but I loved drawing and cooking too. I hadnt enjoyed training to become a nurse and, when I studied architectural draughtsmanship, I found that every day was the same. So, halfway through my course, I decided to travel for six months, learn a different language and see if I enjoyed working in a kitchen. I came to London, and I fell in love.

One of my friends from home had a boyfriend who worked in a French restaurant called Simply Nico. When I went there to speak with the chef, he said, you dont speak any English, you need to start as a KP. I was ready. I may have been unable to talk, but I showed my enthusiasm and ambition in other ways. If I had to peel the potatoes, I was the fastest at peeling the potatoes. If I had to peel the onions, I was the fastest at peeling the onions. I worked really long hours but everything was new to me and I was happy. After about four weeks, they said, OK, well put you on salads. Then I moved to hots and I started to speak English in the kitchen. The only way to really understand how to run a kitchen is to start from the bottom and work your way up, and it was at Nico that I realized that being a head chef isnt just about cooking in fact, thats almost the easiest part.

Being the only Spanish woman in a French kitchen wasnt always easy. Its a different world now, but at the time I really had to stand my ground. After a period working at Gaud, a Spanish restaurant (now closed) in Clerkenwell in London a really happy time in which I made some of my best friends I moved to Fino, a small restaurant in Fitzrovia that Sam and Eddie Hart opened in 2003. Fino was probably the first proper Spanish restaurant in London and it was there, almost five years after I started working in restaurant kitchens, that I started to cook what I really wanted to: lots of small dishes and little bites packed with flavour, instead of traditional starters and mains. This way of eating has a different vibe: its less formal, more fun, and theres more opportunity for playing around with ingredients. Working at Fino gave me the confidence to be myself, and I began to cook Spanish recipes with ingredients from the UK at the same time as building relationships with suppliers that enabled me to get amazing Spanish ingredients like goose barnacles (a crustacean that is a delicacy in northern Spain).

Four years after opening Fino, Sam and Eddie opened another restaurant, the first Barrafina on Frith Street in Soho. Again, I planned the menu it was similar to Fino, but with more of a Basque influence, and more tapas. It was stressful because more dishes equals more ingredients and more to do. On top of this, there were no reservations, meaning we didnt know how many people would show up. Id always worked in kitchens that were tucked away from sight, and for the first time I was going to have people watching how we were doing everything. The day we opened there was one guy waiting outside, but slowly people started to look through the window and come in. After an hour or so, we were full although you only needed twenty-three people to fill the restaurant! As soon as I began to cook, I forgot about everyone watching. Over the years the reaction of the customers at Barrafina has taught me so much; I can immediately see when people like something (or dont), and this has helped me to make my recipes better. When the second Barrafina opened on Adelaide Street in Covent Garden in 2014, I wrote a completely new menu. I didnt want to serve the same dishes, because were not a chain, and thats not my style of cooking. I like when people talk about having a favourite out of the three restaurants (Drury Lane opened in 2015), as they all have their own identity, though they share the same atmosphere and brilliant service. In 2014, Barrafina was awarded a Michelin star. When the founder of Barrafina, Sam Hart, called to tell me, at 7 a.m. or so, I was like, What are you talking about? I didnt think Id ever have a Michelin star because thats not my style of cooking, and Barrafina isnt a Michelin type of restaurant although the service is exemplary. Its good that the way people think about these things is changing, though: eating fantastic food doesnt have to be so formal. For me, the point of going out is to have a great time. Barrafina has retained its star for three years now, and the team work so hard and really deserve it.