Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

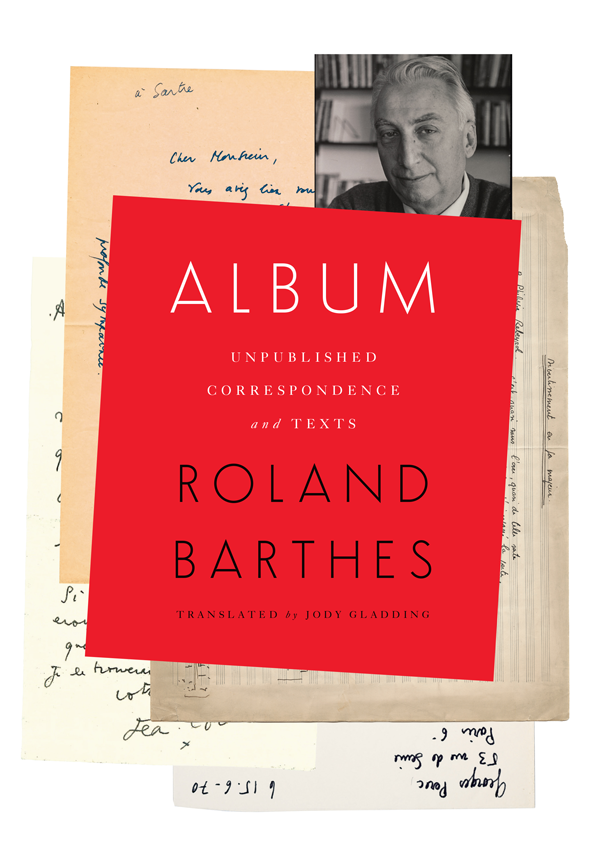

ALBUM

European Perspectives

European Perspectives

A Series in Social Thought and Cultural Criticism

Lawrence D. Kritzman, Editor

European Perspectives presents outstanding books by leading European thinkers. With both classic and contemporary works, the series aims to shape the major intellectual controversies of our day and to facilitate the tasks of historical understanding.

For a complete list of books in the series, see .

ALBUM

Unpublished Correspondence and Texts

ROLAND BARTHES

Established and presented by ric Marty

With the assistance of Claude Coste for On Seven Sentences in Bouvard et Pcuchet

Translated by Jody Gladding

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Album: Indits, correspondances et varia copyright 2015 ditions du Seuil

English translation copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54588-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Barthes, Roland. | Marty, ric, 1955 editor. | Gladding, Jody, 1955 translator. | Coste, Claude author.

Title: Album: unpublished correspondence and texts / Roland Barthes; established and presented by ric Marty; with the assistance of Claude Coste for On Seven Sentences in Bouvard et Pecuchet; translated by Jody Gladding.

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, 2018. | Series: European perspectives | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017039160 | ISBN 9780231179867 (cloth: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Barthes, RolandCorrespondence. | CriticsFranceCorrespondence.

Classification: LCC P85.B33 A4 2018 | DDC 801/.95092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017039160

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Evan Gaffney

Cover images: photo of Roland Barthes by Arthur Woods Wang, Photographs of Authors and Ranchers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; draft of letter from Roland Barthes to Jean-Paul Sartre: Roland Barthes Collection, Bibliothque Nationale de France (BNF); Divertissement in F Major, dedicated to Philippe Rebeyrol: Philippe Rebeyrol Archives, lInstitut Mmoires de ldition Contemporaine (IMEC); note to Roland Barthes from Jean Cocteau: Thanks to the Comit, Jean Cocteau; letter to Roland Barthes from Georges Perec: Roland Barthes Collection, BNF.

CONTENTS

ric Marty

Translated by Kate Briggs

ric Marty

Reading in R. B. what he does not say but suggests, I imagine that for Werther passionate love is only a detour to death. After reading Werther , there were no more lovers, but more suicides. And Goethe passed off to Werther the temptation of death, but not his passion, writing not to keep himself from dying but through the movement of a death that no longer belonged to him. That can only end badly.

Maurice Blanchot

Posthumous time is as complex and subtle as life time. It is woven of events, surprises, waiting, mourning (survivors die as well), encounters (new readers), betrayals, neglect, alliances, sorrows, disappointments, and of course joys. In that posthumous time, there is also a place for what Proust called temps retrouv , that time when forgotten feelings, scents, words, truths, and faces are revived thanks to the effects of recollection. In putting together this album celebrating Roland Barthess centenary, I continually had that feeling of accessing a temps retrouv , immediately prompting a concern for helping readers gain access to it as well. From the letters from the sanatorium, where Barthes is very often immersed in the darkness of disease and its surrounding silence, to the last letters that revive Barthess exchange with another writer now deceased, Herv Guibert, strange and often scintillating bits of the past emerge. It is a past that may well have constituted for Barthes himself, in his lifetime, an invisible part of his life, a virtual part. We remember so little of the letters we have written and even when we do remember them, what can be gathered from themwhat is gathered here from so many exchanges with so many correspondentsconstitutes an expected tableau, a tapestry woven of so many threads that even its author could not have imagined it.

This album comprises five large sectionspreceded by a prelude devoted to the death of Barthess fatherin which the letters exchanged, written, and received by Barthes constitute the main part of the text, with inclusions of unpublished material (from Barthess text from 1947 on the sanatorium to his notes on Vita Nova). Chronologysince it is an entire life we find herewas our guide, as well as our desire to let that life unfold through what correspondence expresses best: friendship. Thus we have in some way inflected the chronology through a form of cartography whereby chapter titles are also something like stages in a writing career, in a writers life. It is worth noting, moreover, that Barthes may be among the last of our authors for whom producing a posthumous collection of letters is possible, given the evolution of the act of writing itself, since his death, and the gradual disappearance of letters that makes the epistolary act revolutionary. That fact as well confers upon this collection a flavor or scent of a time regained. It is also the time regained of a certain idea of what writing means.

Nevertheless we know that a correspondence is an artifact, and it is an illusion to think we might rediscover Barthess actual life there. Thus this collection is not in any way an exact reflection of things or a life, except as an erotic of the everyday, even if we may think that some of the letters in this body of complex and moving materials may have something seemingly decisive about them. Just as others are seemingly insignificant, simply a brief note or polite response. Nevertheless we have included them because, for those who love letters, in the very brevity of a polite phrase there lies an entire message full of meaning. Sometimes it is simply the writers name itself that matters because it allows us to complete the cartography of friendship that we are attempting to draw.

Letters are lost, burned, and torn up, and this collection does not pretend to be exhaustive. Thus the reader will not find here Roland Barthess letters to some of those closest to him: Franois Wahl, his friend and editor; Severo Sarduy, Wahls companion; Jean-Louis Bouttes, whom Barthes refers to as the Friend in his final work, Vita Nova . They did not keep his letters. Not long ago I myself, for example, destroyed the letters that Roland Barthes had sent to me. The decision to include only unpublished letters led us to omit those Barthes wrote to Frdric Berthet, Michel Foucault, who was Barthess closest friend in the 1960s, with whom he went out almost every evening, often to wrestling halls or, for example, to see a B movie like Maciste in a movie theater in Belleville, as on a January evening in 1963, is only represented by a very small sampling. There is only one letter from Barthes to Pierre Klossowski and none from Klossowski to Barthes, although they were very good friends. Other names are missing or poorly represented. There are no letters from or to Marguerite Duras, whom Barthes visited often in the 1960s, or from Henri Lefebvre, for example, with whom Barthes was very close. These absences are compensated for by presences that are unexpected (Maurice Blanchot), moving (Jean Genet), or surprising and therefore all the more delightful (Georges Perros).