Contents

Guide

Pages

The Friendship of Roland Barthes

Philippe Sollers

Translated by Andrew Brown

polity

First published in French as Lamiti de Roland Barthes, ditions du Seuil, 2015 This English edition Polity Press, 2017

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1335-2

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sollers, Philippe, 1936- author.

Title: The friendship of Roland Barthes / Philippe Sollers.

Other titles: Amiti?e de Roland Barthes. English

Description: Malden, MA : Polity Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016029143| ISBN 9781509513314 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509513321 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781509513352 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Barthes, Roland--Friends and associates. | Sollers, Philippe, 1936---Friends and associates. | Barthes, Roland--Correspondence. | Sollers, Philippe, 1936---Correspondence. | Linguists--France--Correspondence. | Critics--France--Correspondence. | Authors, French--20th century--Correspondence.

Classification: LCC P85.B33 S6513 2017 | DDC 410.92 [B] --dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016029143

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Translators Note

Sollers often refers to Barthess texts without giving publication details or page numbers; I have translated all the quotations from Barthes afresh, with due thanks to the excellent translators who have served Barthes so well.

The pieces gathered in this small volume vary in style. Friendship is a memoir in the form of an improvised monologue; R.B. deploys the language of 1970s French intellectual polemic at its prickliest and most elliptically formulaic; the Appendices look back, at times wryly, on the trip to China that Barthes and Sollers undertook, and also re-state Sollerss claim that Barthess political analyses have lost none of their trenchancy in an age when a new mutation of Poujadism (paranoid, protectionist and xenophobic) is on the rise and not just in France. Barthess letters show a more intimate and unguarded side of him than we usually see: he was clearly an affectionate, loyal and caring friend. I have tried to stick fairly closely to the different tones in these pieces, with their sudden tangential breaks and occasional obscurities. I have kept annotation to a minimum: to explain what Sollers meant, in 1971, by dogmatico-revisionism, or to detail all the writers, publishers, academics and review editors mentioned by Sollers and Barthes, would involve a mini-history of French intellectual life since the 1960s. It seems less important to dwell on the doctrinal or purely personal polemics of forty years ago than to get a sense of why Sollers thinks that now, more than ever, might be a good time for us to be reminded of Barthess lifelong and lucid awareness of the ever-present menace of terrorism.

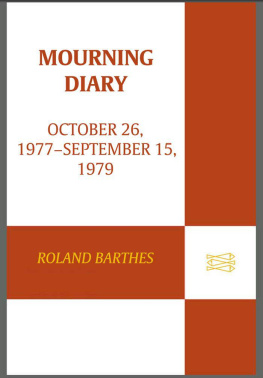

FRIENDSHIP

The death of Roland Barthes, on 26 March 1980, came as a terrible shock to me, and its still with me, it just wont go away. A word he loathed, referring to an event that he found heartrending the death of his mother was mourning. Mourning Diary is a good title, but its not about mourning. Its about what he called, using a word to which he restored its full force, sorrow. Sorrow is completely different from mourning which, the psychoanalytical accounts tell us, lasts two years, etc. I still experience this sorrow even today. Just as intensely as then. Sorrow, first of all, that this incident was obscured, in the news I initially received, by a great deal of uncertainty. It was practically as if it must not appear to be a fatal accident. I can still see and hear Franois Wahl saying: No, its just a minor accident, hell recover, hes absolutely fine. Was it the lunch with Franois Mitterrand, who was elected French President the following year, that led to this cover-up? Its not serious! As if Mitterrand had cast the evil eye on Barthes. I was finally informed that he was in a bad state, really bad dying and I just had time to go with Julia Kristeva and hold his hands. He recognized us, he said thank you. We told him we loved him. But it was the end. I always found this odd because what we lack is a discourse by Barthes on Mitterrand, a mythology of that future left-wing president. So presidents of France come and go but we dont have Barthess account of this lunch his account.

And while Im on the topic of French presidents, Ill mention, if I may, the fact that when Julia Kristeva was decorated by Nicolas Sarkozy, he told her all of a sudden that she had been friends with Roland Barthez (sic). There was laughter in the audience, immediately stifled. All the same, this slip of the tongue depicts, in my view, the state of continual degradation in French political life and my feeling that we need to start again from scratch.

So we miss Barthes simply for his way of being, his body. He could play the piano; drawing came to his hands in a completely spontaneous way; his handwriting it was a pleasure to see his writing in blue ink, his whole way of writing; then there was his voice, the timbre of his voice, his diction... Where are we now when it comes to voices? Who still has a voice? There are two, for me, obvious voices: first, Lacan when he started improvising (since he thought aloud, the fact of speaking gave him things to think about), and then Barthes: he starts writing but ultimately he finds things to write about because hes starting to write. Its all a matter of voices, in other words something inspired that transpires in a certain breathiness, a certain difficulty, in Barthess case, due to the illness he had overcome, after a struggle. What we hear, stemming from all of this, is a very odd detachment.

The first text Barthes wrote on me dates back to 1965, in the review Critique, and it was about my book Drame. So that was fifty years ago. Has todays literary situation emerged from the desert of that period? Barthes is more contemporary and precise than ever and I am going to deliver a political encomium on him, since thats how he always perceived the bedrock of his life, namely the fact that literature grants us a quite particular way of looking at politics. As evidence, we can point to the very fine text he wrote as a young man on Platos Crito, in which he imagines a Socrates who does not commit suicide after all, things might have turned out differently, no one is obliged to commit suicide, to obey the laws of the city, to sacrifice him- or herself. In 1934, Barthes was nineteen, he was at the Lyce Louis-le-Grand and this was when, he says, he started a little literary review it wasnt a literary review but an antifascist republican defence group called DRAF, which we set up to defend ourselves against the arrogance of the patriotic youth groups that were in the majority in the final year at school. What are things like now?