Publishing Director: Sarah Lavelle

Copy-editor: Eve Marleau

Art Direction and Design: Nicola Ellis

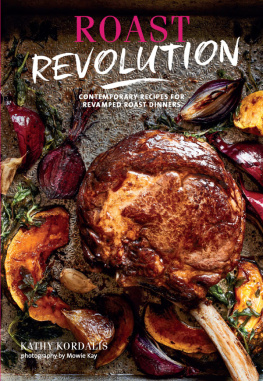

Photographer: Mowie Kay

Food Stylist: Marina Filippelli

Prop Stylist: Louie Waller

Production Director: Vincent Smith

Production Controller: Katie Jarvis

Published in 2019 by Quadrille, an imprint of Hardie Grant Publishing

Quadrille

5254 Southwark Street

London SE1 1UN

quadrille.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders. The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Cataloguing in Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Text Catherine Phipps 2019

Photography Mowie Kay 2019

Design Quadrille 2019

eISBN 978 1 78713 336 5

Oven temperatures are conventional throughout.

contents

The kernel of the idea for this book started with a childhood obsession of mine the popular fairy tale Rapunzel. I was fascinated by Rapunzels poor pregnant mother, who was so desperate with need and desire for the greens in the witchs walled garden that she (or her husband) bargained her daughters life away for them. We so often hear of forbidden or longed-for fruits having a profound impact on a story, but rarely forbidden greens. I had a Ladybird version of the book that gave me a very clear picture of the garden the neat rows of vegetables with those much-desired greens cheek-by-jowl with grids of fat cabbages, danger hinted at by the large patch of foxgloves (perfect for a witchs garden). I remember the thatched cottage with the hint of a forest of trees in the background. I imagined the garden at night, glimpsed over the high, vine-covered wall and pale in the moonlight. It probably along with Mary Lennox kick-started my enduring love of walled gardens. There is something so thrillingly secretive, self-contained and possessed about a walled garden, but when it is functional and productive too it is alive with possibility and gives a certain kind of security the same feeling of well-being you get from a well-stocked larder or still room. I would also imagine the kitchen within, when I expected that not only would the witch (like every storybook old lady who lives close to the wood) eat and cook and infuse and preserve everything she grew in the garden, but everything she could take from the woods beyond, where all the wild leaves grew.

I have read numerous versions of Rapunzel over the years, and I am always drawn to those greens. I used to be reminded of them in the days when I had only myself to feed and was in the habit of walking through my own garden, picking a variety of leaves for a quick vegetarian salad or saut. The thought of a large bowl of wilted leaves, intensely savoury, earthy yet refreshing, slightly bitter and metallic, with a succulent, salty tang appealed to me. This is how they tasted in my imagination complex and obviously good for you; very satisfying. I used to wonder what kind of greens they were imagining a chard or a fatter, more substantial spinach, or the mixture of wild greens collectively known as horta in Greece, which I gorge on every time I am there. The clue was in the name. Rapunzel is the German name given to rampion, campanula rapunculus in fact, a type of campanula with a pretty, star-shaped bell flower and greens that are, thank heavens, spinach-like (and often used as a substitute), but more succulent with a little nutty bite. It is a lovely thing to grow; messy-looking clumps spill out from a central point for the first year before it shoots up and flowers. Its useful and happy in dappled shade and if you decide to do so, you can eat it cooked or raw just like spinach. Rapunzel is also feldsalat, which we know as corn salad, or mache, or lambs lettuce another useful salad green, but not quite in the same class as the succulent greens I imagined.

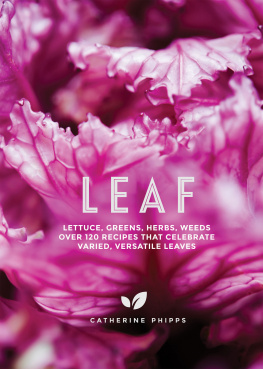

The appeal of that bowl of greens has never left me, and it is part but not all of what I want to showcase in this book. I hope that Leaf is a celebration of edible and aromatic leaves, and all they can offer us. It has been a slightly daunting task, as the scope is so broad, but an absolute joy at the same time, as I have focussed primarily on foods that I love. They are a disparate lot, leaves; just in terms of flavour, the choice is immense, something to suit every mood or craving. Consider the bitterness of endives and wild dandelion; the pungency of wild garlic, mustard and curry leaf; icy, spicy menthol from mint and shiso; citrus from verbena and French sorrel, resinous astringency of pine and rosemary, mellow nuttiness of butterhead lettuces and sprout tops, deeply savoury, saltiness of seaweeds and agretti and the succulent, thirst-quenching coolness of iceberg, purslane and borage. I could go on and on, and this is before I even start thinking about how much we can change and layer all these flavours, through cooking, fermenting and pairing.

Visually and texturally, leaves are a riot the palest shades of white and yellow; every possible shade of green; from early season fluorescence via bright pea green and cobwebby silver to deep, almost black forest; they can be burnished browns, purples, reds, dainty rose pinks, variegated in numerous combinations. They can be crisp and tightly furled torpedoes or bullets (think endives and Brussels sprouts), floppy with a peony blowsiness about them (sprout tops, oak leaf lettuce and certain types of chicory), spiky (pandan, puntarelle, pine, rosemary, wild garlic, agretti), crinkly and curly (kale, cavolo nero, savoy cabbage), delicate and feathery (dill, chervil, fennel, carrot tops). They range from the tiniest of microherbs those two leaves poking out of the soil to show that germination has been successful, as small as a babys fingernail, to huge elephant ears, a meal in a leaf. They can be dull, or with a rich, glossy sheen, diaphanous or thick, protected by hair or thorns. It is no wonder that they all cook very differently too stiff and robust leaves that keep their shape and some of their texture, others that wilt down to almost nothing, and those that do not yield or soften at all. They offer every texture from a crunch, to a scratchiness if not carefully prepared, or can collapse into something as smooth as silk.

The uses of leaves are myriad. We are most used to eating them as side dishes, within salads and soups, or as a flourish of green to add to stews, potages and curries. But there is so much value in making them the main part of the meal roasted or grilled heads of leaves can be as satisfying as a steak, in part because they still have a tough resistance at their core. I dont mean that we should all immediately become vegetarian or vegan this is definitely not the book for that but what I do like doing is using meat, fish and dairy as a flavour accent to the vegetables rather than the other way round. I feel the same way about herbs. Of course, I use herbs for flavour in a sauce, as a garnish, added at various points to a dish, fresh and dried, but I also emulate clever cuisines that treat them as the main event. What I like to do most of all is layer everything up together dried or woody herbs or stems, loose or bouquet garnied at the beginning of the cooking time, greens as part of the main bulk, and more herbs for those fresh hits of flavour at the end.