Para mis ms queridos, Rosie, Bryana, y Cid. Y por supuesto, para Toita.

CONTENTS

Table of Contents

Guide

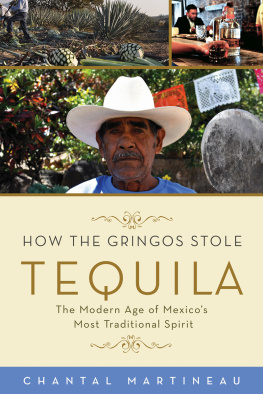

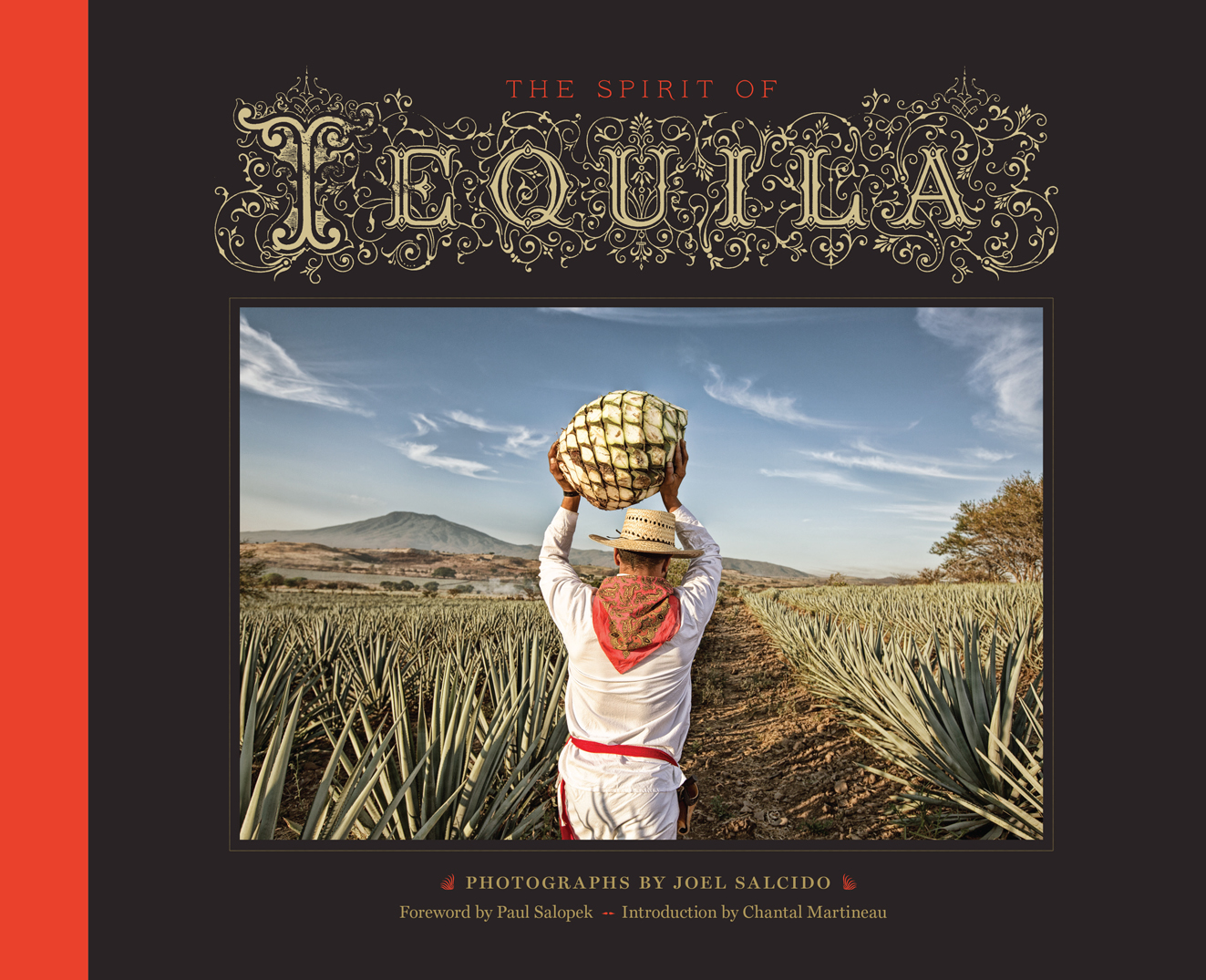

Agave tequilana Weber Azul is a delicate and waxy blue, like certain hues of woodsmoke, or like the blued shadows that pool in the rincons of the Sierra Madre Occidental, the wild mountain range that knuckles down the western edge of the Mexican state of Jalisco.

I grew up in Jalisco, the birthplace of tequila, the famed spirit these blue agave plants so generously yield. Blue agaves lined the dirt streets of my colonia. We schoolboys carved our names and much worse into their fleshy spikes of leaves. We deployed their tall flower stalkssome towered so high they poked rain out of the passing gray monsoon cloudsas spears. Once we were old enough, and sometimes not old enough, we sipped the fermented juices of the blue agave, a universal rite of passage in the Mexican altiplano.

Unlike its brother and sister liquors (whiskeys, gins, vodkas, chachas, ryes, bourbons, scotch, etc.), the raw material of tequila is neither seeds nor roots. No, it is the plants very core, its heart. The good jimador walks his glaucous blue fieldsin the gentle foothills, lets say, above old Zapopanappraising his crop before the harvest. He looks for many things: The cactuslike agaves must be between four and eighteen years old to give up their best juice. The moisture in the soil and season of the year are also important. The dry weeks just before the first rains are best, as they concentrate the sugars in the agaves swollen corazn.

The good harvester is always listening to this enigmatic heart. He knows that within it beats the wingflick of the bat that pollinated his plants. It holds the pulse of the yellow sun, the long, lingering cores of summer afternoons. It drums with the raindrops that in Mexico fall straight and silver and hard. He takes the agaves heart in his rough hands and squeezes its essence into a small glass. He offers it up to you.

I regret to report that I do not drink tequila often anymore. My body has seen too many wars. But I remember the color of those plantationstheir mesmerizing cool hues in the rippling heat of the subtropics. The blues of childhood.

Tequila, like Mexico, is mestizajea coalescence. When pulque, the fermented nectar of Mexicos indigenous world, embraced the Spaniards copper alambiques, or stills, tequila was born.

Mexicos iconic drink is deeply rooted in a past that is both complex and immense. As early as the sixteenth century, the national drink of Mexico was known as vino de mezcal, from the Spanish word vino, for wine, and the Nahuatl word mezcal, for agave.

The mezcal of the Nahuatl culture played an enormous role in the lives of Mesoamericans. Not only was agave critical for sustenance; it could also be used in the making of shelter, clothing, and tools. Mayahuel, a Venus-like divinity that personifies the maguey plant, became the symbol of fertility for the Aztecs.

The town of Tequila, or Tecuillan, Nahuatl for a place of work and cutting, is where land, agave, and people came together to produce the iconic spirit of Mexico. It is here, and in other towns in Jalisco, that I set out to explore the contemporary world of tequila. My search led me to the holy trinity of tequila makersCuervo, Herradura, and Sauzawhich began in 1758 with Cuervos mass distillation of blue agave sugars. I also sought out artisanal tequileras committed to the traditional craft of tequila-making, from harvest to bottle.

In this landscape of blue agave, I discovered traditions of culture and religionancient and modern, indigenous and foreign. All were a reminder of my own complex Spanish and Native American mestizo heritage. Childhood memories resurfaced, decades after I stepped across the Rio Grande into the United States as an immigrant child of seven.

The photographs from this journey reflect the mystical space where the weight of history and the bounty of the earth blend into a spirit called tequila. It is the elixir that remains the guardian of Mexicos landscape, tradition, and identityindeed, the ancient lord of fire with a savage smile.

A silvery blue plant. A crystal clear liquid. How one becomes the other isnt a miracle. It involves science, craft, and a good deal of hard work. The iconic liquid export, distilled from the native blue agave plant, has been made in Mexico for at least four hundred yearssome believe centuries longer. The spirit and its raw material have been intricately tied to Mexicos history, culture, and mythology since the time of the Aztecs.

Most of us dont think of tequila as a cultural product. Maybe the idea that a bottle on the back bar at the local watering hole might be culturally and historically significant doesnt occur to us. Or perhaps its the memory of that first (or worst) experience with the spirit. Shots with salt and lime, or frozen margaritasthese were once the standard introduction to tequila.

These days tequila is often sipped neat, like fine scotch or cognac, or mixed into artisanal cocktails that have nothing to do with a margarita, much less a premixed one. The spirit comes bottled in exquisite crystal decanters, and a number of brands are backed by celebrities or billionaire entrepreneurs. Its not just that the spirit has changedalthough it has, as much better incarnations are more readily available than decades ago. Public perception of tequila is also shifting. No longer is it deemed party fuel, something to be slammed during spring break by hooting coeds. It can be a spirit with sophistication and intrigue. And yes, it is a cultural symbol for Mexico, one with a rich and complicated history. Just how it evolved from a rustic regional specialty to a luxury good is a long and winding tale.

Its a story that begins with a native plant, an extraordinary plant, called agave. Agave are large perennial succulents that look like aloe and are often mistaken for cactuses. Taxonomically speaking, they are more closely related to asparagus. More than two hundred varieties exist, and almost all are indigenous to Mexico. Blue Weber (agave, tequilana) is the variety used to make tequila. Many others, like espadn, the genetic ancestor of blue Weber, are used to make mezcal. Henequn, a variety that thrives in the southern part of the country, was widely used in textile manufacturing in the early part of the twentieth century (until DuPont invented nylon in the 1930s, devastating the henequn industry).

Take a drive through tequila country and youll see waves upon waves of steely blue from the road. These are agave fields. Researchers believe that agave has been consumed in Mexico for at least eleven thousand years, making it one of the earliest cultivated crops in the Americas alongside squash and maize. Agave was used for everything from food and shelter to cultural production. Early Mexicans were known to weave its dried leaves into clothing, bedding, and roofs for their homes. The fine needle at the tip of each spiny leaf was used to sew fabric and for drawing, and in the bloodletting ceremonies the Aztecs were so fond of. This deep reliance and connection to the agave is echoed in its prominent place in Aztec mythology.