White Boy copyright 2019 by Tom Graves. All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form, except for inclusion of

brief quotations in a review, without permission of the publishers.

Print book ISBN: 978-1-942531-31-9

eBook ISBN: 978-1-942531-32-6

Cover design: Martina Voriskova and Patrick Alley

Layout: Patrick Alley

Front cover photograph: Tom Graves, 1 st grade school photograph

Other Books by Tom Graves

Fiction

Pullers

Aesops Fables with Colin Hay (audiobook)

Nonfiction

Crossroads: The Life and Afterlife of

Blues Legend Robert Johnson

*winner of the Keeping the Blues Alive Award

Louise Brooks, Frank Zappa, &

Other Charmers & Dreamers

Graceland Too Revisited

(photography with Darrin Devault)

DEVAULT-GRAVES DIGITAL EDITIONS

Devault-Graves Digital Editions is an imprint of

The Devault-Graves Agency, LLC

Memphis, Tennessee.

The names Devault-Graves Digital Editions, Lasso Books, and Chalk Line Books

are all imprints and trademarks of The Devault-Graves Agency.

www.devault-gravesagency.com

Authors Note

For the sake of protecting the privacy of some of the people named in this memoir who are still living, I have changed or altered names. In every other respect, however, this is a true account.

Drinking Out of the Colored Fountain

I AM FROM A racist family. I was educated in a racist school. I was a parishioner in a racist church. I live in a racist city.

This being Memphis, however, the racism is complex, ironic, and like Einsteins concept of time seems to fold in on itself. In my childhood the world seemed to be divided two ways: by gender and by race. There were men and there were women, and there were white people and there were black people. And that was all there was to it. I was only vaguely aware that there were others who fell outside those parameters. This state of affairs seemed logical to me. God created man and woman and he intended for them to have children, to be fruitful and multiply as the book said. People grew up, got old, died, and went to heaven, or if they were bad to that other place. And for reasons we didnt really understand, he created white people to show black people how they should properly live. That white people were superior to black people didnt even need suggestion. That factalong with the word niggerwas in the very air we breathed in Memphis in the 50s and 60s .

There were restrooms for girls and restrooms for boys. There were restrooms clearly marked for whites and those clearly marked for coloreds, which was the polite way in that time to refer to niggers. I knew those signs and obeyed them long before I hit first grade in 1960 and learned to read. There were also water fountains with the delineations white and colored and we were told not to drink out of their water fountains. Somewhere in the celluloid haze of films I have watched over the years, I remember a scene of a black boy drinking out of the colored fountain and he glances around to see if anyone is looking and steals a sip from the white fountain. Im here to tell you that white children, myself most certainly included, did the same thing in reverse, drinking out of the colored fountain when no one, especially our parents, was looking. To my surprise, the water did not taste different.

I was born in 1954, and because Im either blessed or cursed with a very vivid and accurate memory of my childhood can remember the racial divisions in the South with crystal clarity. I remember how, as my family traveled to their birthplace in Pine Bluff, Arkansas to visit their kinfolk every few months, we would beg to stop at an ice cream stand in Clarendon, Arkansas on every trip. Whites ordered from one side of the building and blacks ordered from the other side. I do not remember that any signs were posted. That was just the way things were and everybody in the small town knew the drill.

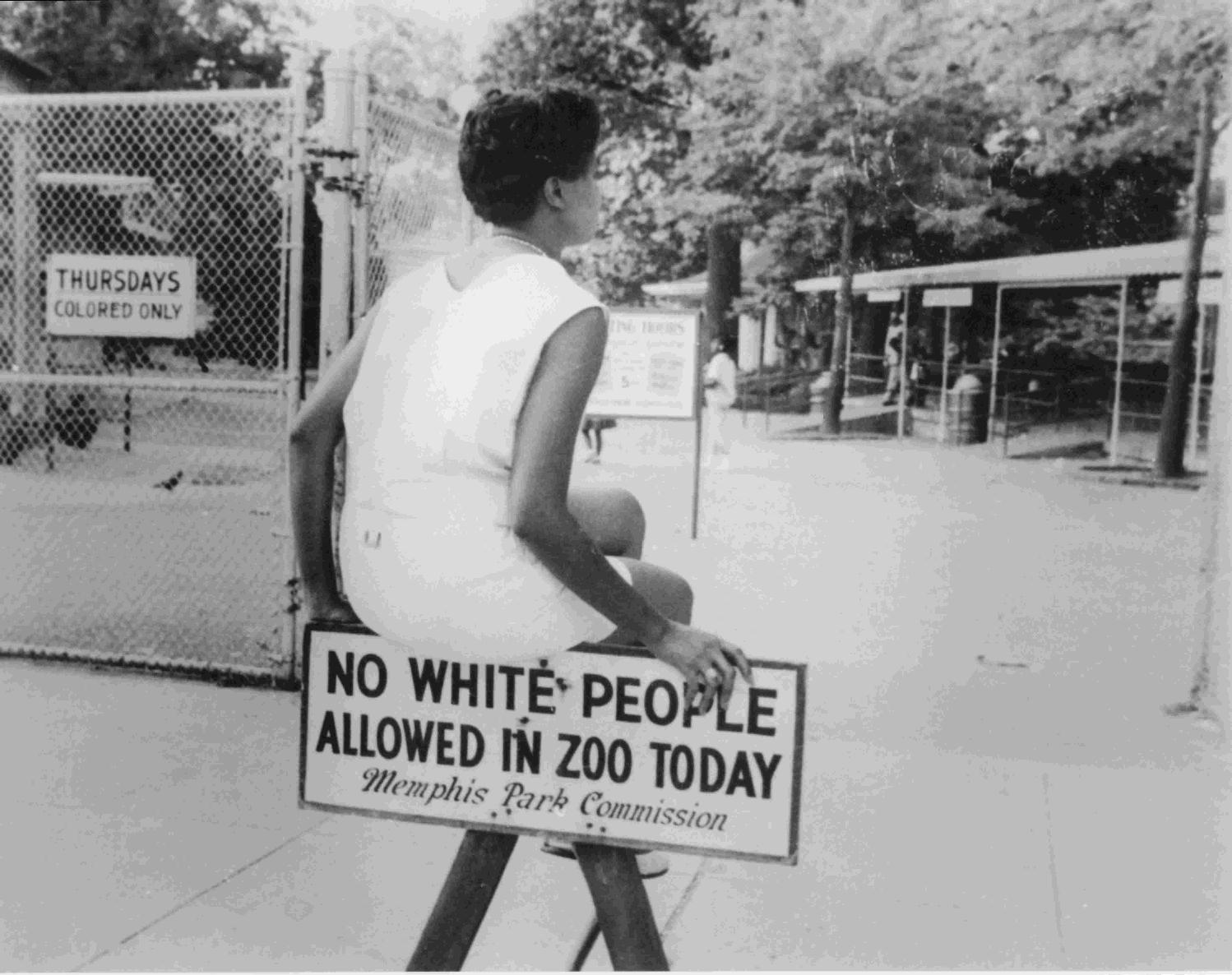

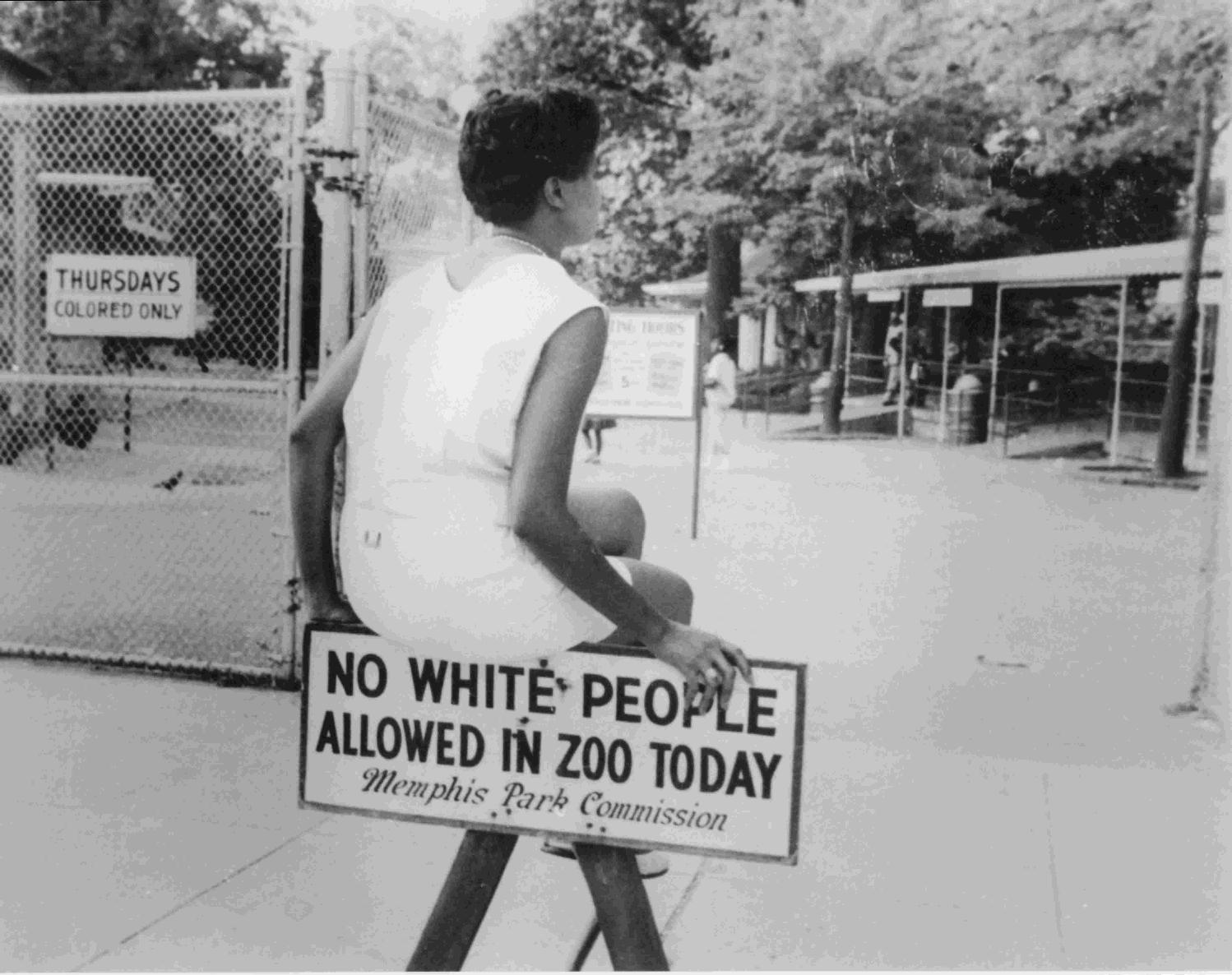

I also remember that the Memphis Zoo, one of my favorite places, had one day per week, Thursday it has been confirmed, reserved exclusively for blacks. Nigger Day as we called it in those unenlightened times. The late Ernest Withers, the great African-American photographer from Memphis who was a friend of mine, has a justifiably famous photo of a sign posted outside the zoo that says No White People Allowed In Zoo Today with a background of black Memphians blithely walking beyond the gates, no whites in sight, and a black woman sitting on the sign. There was also a Nigger Day at the Fairgrounds Amusement Park.

One of my first inklings that something wasnt right with the black and white equation was when our family was picnicking with some old family friends who were visiting from Florida. There was discussion of everyone meeting again at the zoo in a few days.

I tugged at my Dads sleeve and whispered, Dad, we cant go on that day. Thats Nigger Day.

My Dad was a fair man despite his racist leanings. Without fail he rooted for the underdog in almost any given situation and even though he had what the Graves family referred to as the Graves temper, I never heard him say a cross thing to anyone in day-to-day life, whether white or black. Now, if someone was giving him some grief or a hard time, like the comic book hero the Human Torch he could turn his flame on. He brooked no nonsense. Yet I cannot imagine him giving away candy treats to a group of childrenhe loved kidsand not making sure the black kids got an equal number of candies as the white kids. That just wasnt in his nature.

But just let him read the headlines in the local paper about integration or civil rights or a protest downtown and black thunderclouds would form over his head and his ire and dismay would find form in long monologues at the dinner table, monologues at least until I was old enough to start questioning some of his ideas and then dinnertime became a verbal sparring match .

When I told Dad we couldnt visit the zoo on that particular day he replied, Son, they cant go on our days, but we can go on theirs.

Even at five or six years old, this struck me as a queer deal indeed. They cant go on our days but we can go on theirs .

This wasnt the first clue that something was wrong. The first would have to be singing that Sunday School mainstay, Jesus Loves the Little Children. The song specified that Jesus loved them one and all equally, red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in his sight. The illustrations that accompanied the song sheet in our Sunday School books showed a very Caucasian Jesus surrounded by children of all races. The message of equality was quite clear, even in a church that was lily-white.

So, if Jesus, who I had been taught from birth was my Lord and Savior, the one I said my prayers to every night when I went to bed, saw no difference between black children and white children, then why did they live over in Niggertown, which was demonstrably poorer and shabbier than the white parts of Memphis, and why did they have their own churches and their own histrionic manner of worship and we couldnt be friends with them? Why were there separate restrooms, water fountains, places to sit in the movie theater, seats on the bus, kitchen entrances at restaurants, separate waiting rooms at the doctors office?

Next page