The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR

Elsie Bolton, 18981984

Edna Vaughan, 19021981

CONTENTS

Monday, April 30, Midafternoon to Tuesday, May 1, Late Afternoon

Tuesday, May 1, Late Afternoon to Wednesday, May 2, First Light

Wednesday, May 2, Early Morning to Thursday, May 3, Dawn

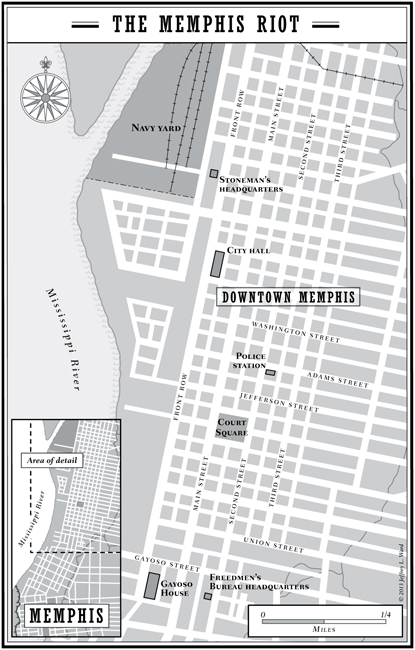

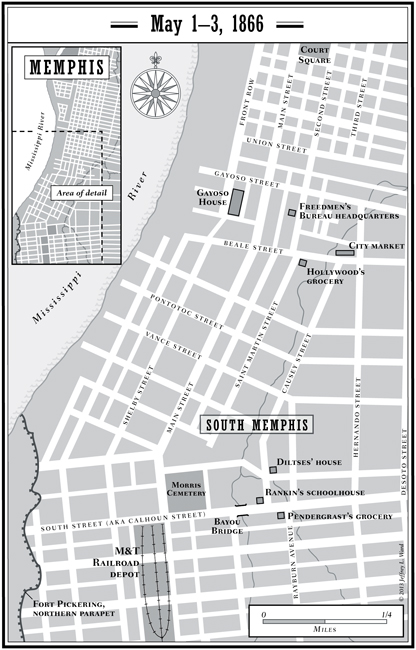

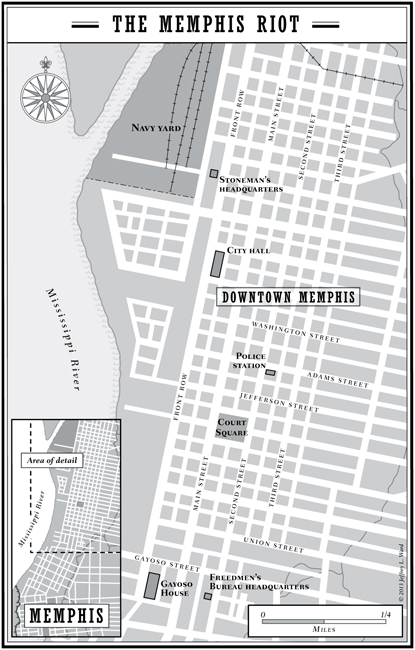

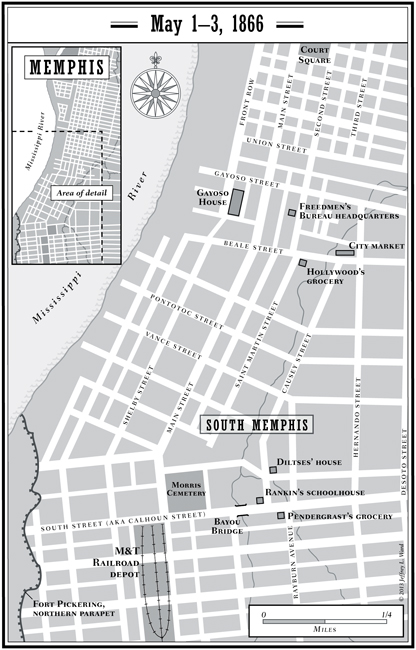

Maps of 1866 Memphis

AUTHORS NOTE

That no book-length study of the Memphis riot of 1866 has been written before this one is surprising, considering that the riot influenced the course of our nations history at a critical juncture, shaping in important ways how Americans thought about the pressing questions of the postCivil War period. But what is even more surprising about the dearth of books on the riot is the enormous amount of evidence available to the historian. The riot is, in fact, one of the best-documented episodes of the American nineteenth century.

In its immediate aftermath, the Freedmens Bureau, the U.S. Army, and a specially formed congressional committee interviewed hundreds of witnesses: men, women, and children, black and white, from all walks of life. Their recorded testimony is a voluminous trove of information not only about the riot but also about the living and working conditions, family and gender relations, racial and ethnic conflicts, and communal institutions, politics, and ideology of the people in Memphis in the spring of 1866. Most who testified were ordinary folks, many of them poor and illiterate, the sort of people whose voices are absent or only faintly heard in the vast majority of sources we have from that era.

One of my intentions in this book is to revive, as it were, the individuals who gave Memphis its vitality and character, and who may have died in the riotto restore to them the personhood that death and history have taken. This seems especially important in the case of the freed people, some of whom were emancipated only a year or so before the riot, and probably forty-six of whom were murdered in the rioting. They were newly visible in their own time and almost uniformly illiterate, and so unable to bequeath their actions, thoughts, and hopes to posterity. It is a historical and moral imperative to remember as many as we can as individuals, not as a mass of people whose characteristics can be summed up in a paragraph, and certainly not as the dull-witted, unimprovable flotsam many Rebels (and many Yankees) saw them as.

Another of my intentions is to illustrate the nature of the violence that has resulted from race hate in America; here, too, the rich sources make possible an unusually vivid portrait. The events in Memphis in the spring of 1866 were so appalling that it is perhaps hard for many of us to fit them into our understanding of our nations past. We may struggle to recognize any common ground with the bloodthirsty rioters or the federal authorities who sat idly byit is easier to dismiss them all as products of a uniquely pathological time and place. But when we move from a close examination of the riot to a longer view, the event begins to resonate across centuries. The riot can be seen both as a continuation of older forms of racial brutality and as a harbinger of a new kind of violence: the organized terror Southern whites would carry out against blacks well into the twentieth century. In this sense, the 1866 Memphis riot not only sheds light on a turning point in American history and allows us to write ordinary people back into that history, but also is crucial to understanding one of our original and most intractable matters, the role of race in American life.

Prologue

Memphis, Tennessee, May 2224, 1866

The last 140 miles of Congressman Elihu Washburnes railroad journey from Washington to Memphis spanned the flat countryside of west Tennessee. Cotton plantations dominated the landscape: from the train window Washburne would have seen broad stretches of fenced and tilled land alternating with patches of woods, with here and there a planters manor and a scattering of laborers cabins. Black people were at work in the fields with hoes and plows. The fields were green, not white, for the full ripening of the crop was still months away.

It was Tuesday, May 22, three weeks to the day since the outbreak of the horrific race riot in Memphis that had riveted the nation. Washburne, a long-serving Republican member of the House of Representatives from Illinois, had been charged with overseeing Congresss investigation of the riot. This was an important assignment: the bloody, three-day upheaval, the most sensational event outside Washington since the death of the Confederacy, would no doubt play a key role in the crucial decisions now facing the nation.

Washburne already knew a good deal about the riot and its causes. In the months leading up to the riot he had received letters from acquaintances in Memphis concerning the situation there, particularly the citys racial and political tensions. Newspapers had provided considerable information on the riot itself. Moreover, both the local military commandant and the Freedmens Bureau had already investigated the riot, although not as extensively as Washburne planned to, and he had been informed about their findings.

From these various sources he had learned that there was a bitter, long-standing antipathy between Memphiss blacks and lower-class whites. The Union army had taken the city early in the war, in 1862, paving the way for emancipated slaves from the countryside. This had the effect of greatly aggravating the old bitterness, because the newly arrived blacks began to compete with the lower-class whites for jobs. The city policewho were all white, nearly all Irish immigrants, and notoriously unprofessionalespecially detested the freed people and regularly abused them. The thuggishness of the police went unchecked by the leading civil officials of the city, who were themselves mostly Irish and contemptuous of the blacks. The soldiers of the black U.S. Army regiment that had garrisoned the city until they were mustered out just before the riot were a special target of white resentment; this resentment was not altogether unjustified, however, for the unit was poorly disciplined and some of its men stirred up trouble or committed crimes when off duty. The native-born Southern whites of Memphis had been, with few exceptions, devout secessionists during the warmany hundreds had served in the Confederate armyand they remained unrepentant now, resentful of Union victory and federal authority, furious about their political disenfranchisement, hostile to equal rights for the freed people, and contemptuous of the Yankee newcomers in their city. Almost all the local newspapers were controlled by such Rebels, and in the months leading up to the riot they ran lurid editorials that further inflamed the prejudice against blacks and Northerners.

The riot, which was triggered by clashes between black men and police officers on April 30 and May 1, was an explosion of rage and violence directed against the freed people and perpetrated by the white underclass. Policemen and firemen were among the rioters, as were certain higher-ranking officers of the city government. By the time the rioting ended on May 3, at least forty blacks had been murdered, dozens more wounded, several raped, and many others robbed. Many black churches, schools, and residences had been torched.