Havana Industriales batting practice, Estadio Latinoamericano. Havana

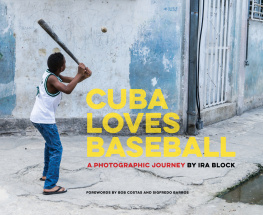

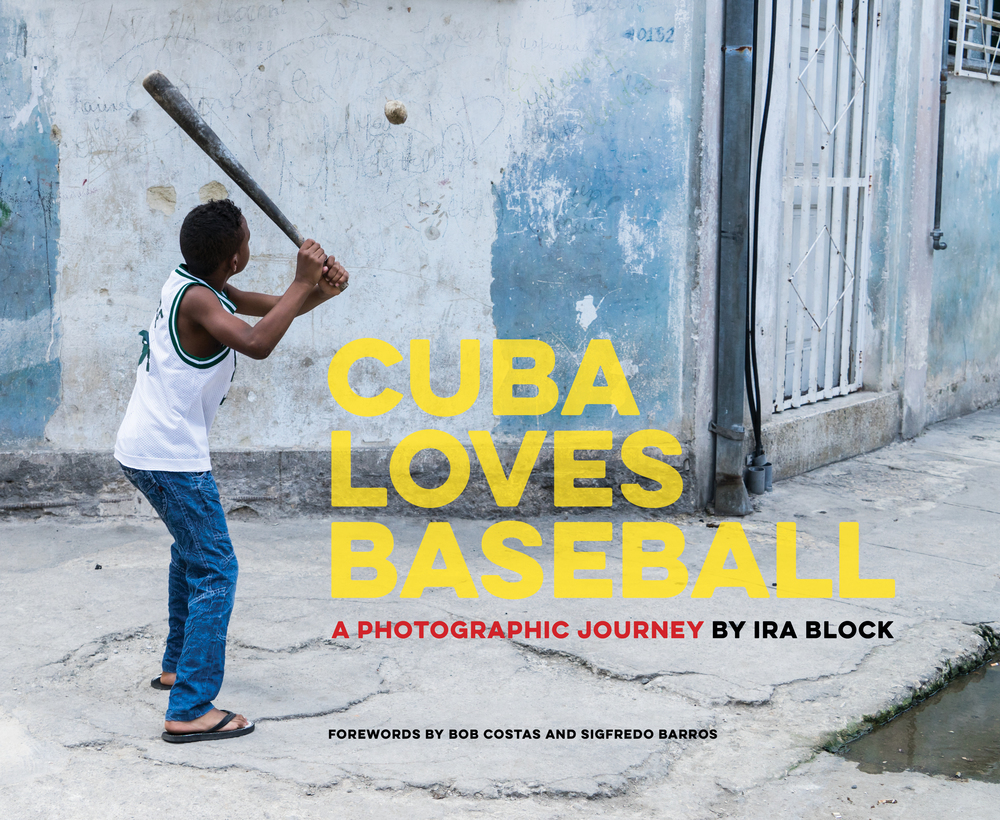

No shoes, no real bat, no worries. Trinidad

Cigar-smoking fan entering Estadio Latinoamericano. Havana

Fans, Estadio Victoria de Girn. Matanzas

Rural road baseball. Jibacoa

Estadio Cristbal Labra. Isla de la Juventud

CONTENTS

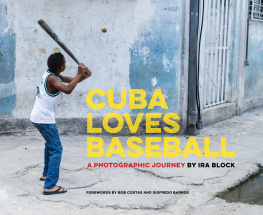

FOREWORD BOB COSTAS

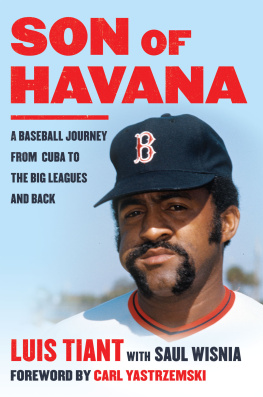

WHEN I FIRST BEGAN to follow baseballto recognize the names, uniforms, and faces on baseball cards and black and white TV screensCuban stars like the great Minnie Minoso, curveball artist Camilo Pasqual, and eventual AL MVP Zoilo Versailles were distinctive presences. They had come to the major leagues before Castros revolution and the enforced isolation that ensued. A bit later, othersTony Prez, Tony Oliva, Luis Tiantwould leave Cuba as well.

As random chance would have it, I saw Tiants major league debut for Cleveland in the summer of 1964. It was a Sunday doubleheader at the original Yankee Stadium. Tiant threw a four-hit shutout, struck out 11, and beat Whitey Ford 30.

By then, the flow of talent from Cuba to the big leagues had stopped or slowed to a trickle. Still, the islands love affair with the game, a love affair that pre-dates the 20th century and includes long-ago legends like Dolf Luque and Martn Dihigo, never waned.

In 1990, I visited Cuba as part of an NBC broadcast of a game between a squad of US collegiate players and the mighty Cuban national team. You didnt need to be a big league scout to see that many of the Cuban players would have been MLB stars if given a chance.

In a time before the Internet, in a place where a satellite dish would qualify as contraband, the fans and baseball officials I met were nonetheless knowledgeable about major league players, past and present. They were eager for anecdotes about Cal Ripken, Ricky Henderson, Ozzie Smith, and Don Mattingly. I had brought along a gift for the man who would act as my translatorthe latest edition of the Baseball Encyclopedia . As he leafed through it, stopping at familiar names, the expression on his face made you believe he half expected each page to give off a beam of light.

During those few days, I took in as much as I could. A visit to Ernest Hemingways home a few miles outside Havana. The wonderful Cuban cuisine. A clandestine meeting with a weathered old man who drove a hard bargain for a box of first-rate Cuban cigars. The 1950s-style cars that made you feel as if you were in a time warp. And the whispered laments of locals who decried the suppressions of freedom in their homeland.

Still, running through it all was an unmistakable and unconquerable high-spiritedness. The music and laughter along the esplanade on a Saturday night. The warmth and kindness of our guides. And everywhere, it seemed, there was baseball. Stickball in the streets and dusty vacant lots. Organized games on the few full-fledged diamonds. A middle-aged, but still athletic-looking, man who told me he remembered batting and battling against Tommy Lasorda in winter ball decades earlier.

These days, despite the hardships, risks, and occasional cloak-and-dagger intrigue still involved, more and more Cuban stars are making their way to the States. Almost to the point where we take for granted the presence of Yoenis Cspedes, Jos Abreu, Yasiel Puig, Aroldis Chapman, and their many countrymen. But the story and the spirit of bisbol in Cuba is too rich and too fascinating to ever take for granted.

Ira Block asked me to offer a few hundred words of introduction for this beautiful book. I guess, at this point, I have done that. But if ever the expression, a picture is worth a thousand words applied, its in these pages. Iras keen and empathetic eye elevates photography to art. Each image is truly worth a thousand words and evokes the vibrancy and joy, the passion and poignancy of baseball in Cuba.

These unforgettable photographs remind us that baseball, in all its various forms, is Cubas national pastimejust as it is ours.

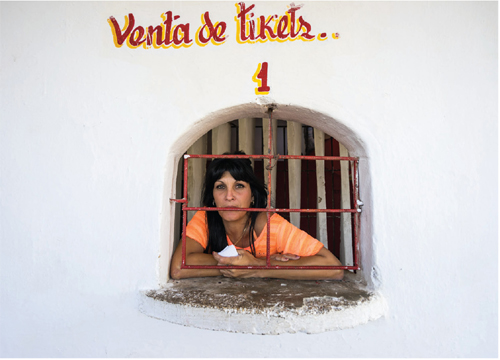

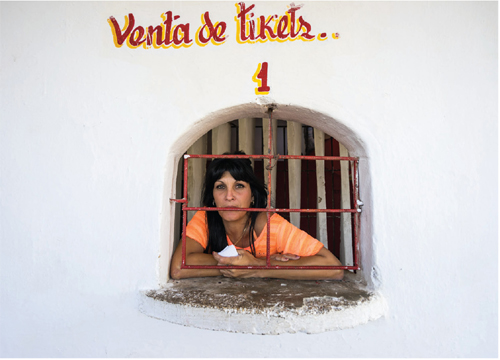

Ticket vendor, Estadio Victoria de Girn. Matanzas

Pregame fans, Estadio Victoria de Girn. Matanzas

FOREWORD SIGFREDO BARROS

SINCE EARLY IN the nineteenth century, Cubans from all economic and social strata have enjoyed playing sports. In years past, young athletes from the islands wealthier families were drawn to sports such as swimming, while those from lower income levels boxed or competed in track and field.

All of that changed dramatically on December 26, 1874. On that day, at Palmar de Junco Stadium in the Pueblo Nuevo neighborhood of Matanzas, Club Havana defeated Club Matanzas, 519, in the islands first official baseball game. Already gaining popularity across Cuba, baseball would soon become a national passion.

Who introduced baseball to the small Antillean island of Cuba? The sports journey to the island began sixteen years earlier in 1858, when ten-year-old Nemesio Guillot, the son of a Spanish immigrant, moved with his brother, Ernesto, and a friend, Enrique Porto, from Cuba to Mobile, Alabama. The three attended a school called Alabama Spring Hill College, where they played baseball when not in the classroom.

Seven years later, Nemesio packed his bat and ball, and the trio returned to Cuba. As soon as they landed, the boys went to Vedado, a crowded neighborhood in central Havana, and played a game they had created. The rules were simple: Three balls caught in the air or on the first bounce would grant to the fielder the right to use the bat.

The popularity of the new game spread quickly among Cuban youth. In 1868, Nemesio and a group of about ten players started the Habana Base Ball Club, which defeated a team made up of the crew from an American schooner anchored in Matanzas. The game even began to replace bullfighting as the islands most popular sport.

At about this same time, however, the Ten Years War broke out as Cuba sought to free itself from Spanish rule. Baseball was banned by Spanish colonial authorities because they believed the game was being used to mobilize opposition to Spanish rule. The ban was short-lived.

Next page