This book has been surprisingly many years in the making and would never have been written without the support of many people. I am very happy to thank my incredible agent Howard Yoon, who encouraged me to write this book many years ago and kept on providing smart, calm guidance; my editor, the fabulous Maria Guarnaschelli, for her editing, wise advice, generosity, and contagious enthusiasm, my superb copy editor Carol Rose, and the rest of the fantastic team at Norton, including editorial assistant Mitchell Kohles, publicity director Louise Brockett, designer Cassandra Pappas, production manager Anna Oler, and managing editor Nancy Palmquist; Stanford University for supporting me on the sabbatical and Stanfords Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences for further support and for providing an intellectual home during the writing, along with the support of the wonderful staff there, particularly librarians Tricia Soto and Amanda Thomas; Eric and Elaine Hahn, who offered the use of their lovely house during other parts of the writing; the remarkable young students over the years who have taken my Stanford freshman linguistics seminar, The Language of Food, especially my collaborator Josh Freedman, who in addition to our joint work described in Chapter 8 read the manuscript and gave suggestions throughout; my amazing cousin and role model, sociologist Ron Breiger, who besides other advice pointed out the work of Andre Gunder Frank; Stephanie Shih for suggesting that I look at the history of macaroons and flour; Chia-Wei Woo, then running the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, who first pointed out the Chinese origins of ketchup; my Mom and Dad for their support (and for the always wise editing suggestions of Dad, still an eagle-eyed reader in his nineties); John McWhorter, Lera Boroditsky, and Erin Dare for superb advice and suggestions throughout the project.

Some of the chapters grew out of pieces I wrote for Slate, Gastronomica, and the Stanford Magazine, where I am very lucky to have had great editors: Laura Anderson, Daniel Engber, Ginny McCormick, and especially Darra Goldstein and Juliet Lapidos.

Finally of course, this book would not have been possible without the ideas, edits, suggestions, and support of my wife, Janet.

Many people over the years gave me advice and ideas, answered questions, suggested resources or people, and spotted flaws; thanks to Alan Adler at Aron Streit, Inc., KT Albiston, Domenica Alioto, Mike Anderson, Mike Bauer, Pete Beatty, Leslie Berlin, Jay Bordeleau, Jason Brenier, Ramn Cceres, Marine Carpuat, Alex Caviness, John Caviness, Victor Chahuneau, Karen Cheng, Paula Chesley, Fia Chiu, Shirley Chiu, Anna Colquohoun, Alana Conner, Erin Dare, Melody Dye, Penny Eckert, Paul Ehrlich, Eric Enderton, Jeannette Ferrary, Shannon Finch, Frank Flynn, Thomas Frank, Cynthia Gordon, Sam Gosling, Sara Grace Rimensnyder, Elaine Hahn, Eric Hahn, Lauren Hall-Lew, Ben Hemmens, Allan Horwitz, Chu-Ren Huang, Calvin Jan, Kim Keeton, Dacher Keltner, Faye Kleeman, Sarah Klein, Scott Klemmer, Steven Kosslyn, Robin Lakoff, Joshua Landy, Rachel Laudan, Adrienne Lehrer, Jure Leskovec, Beth Levin, Daniel Levitan, Mark Liberman, Martha Lincoln, Alon Lischinsky, Doris Loh, Jean Ma, Bill MacCartney, Michael Macovski, Madeleine Mahoney, Victor Mair, Pilar Manchn, Jim Martin, Katie Martin, Linda Martin, Jim Mayfield, Julian McAuley, Dan McFarland, Joe Menn, Lise Menn, Bob Moore, Petra Moser, Rob Munro, Steven Ngain, Carl Nolte, Lis Norcliffe, Barry ONeill, Debra Pacio Yves Peirsman, James Pennebaker, Charles Perry, Erica Peters, Steven Pinker, Christopher Potts, Matt Purver, Michael Ramscar, Terry Regier, Cecilia Ridgeway, Sara Robinson, Deborah Ross at The Manischewitz Company, Kevin Sayama, Tyler Schnoebelen, Amin Sepehri, Ken Shan, Noah Smith, Peter Smith, Rebecca Starr, Mark Steedman, Janice Ta, Deborah Tannen, Paul Taylor, Peter Todd, Marisa Vigilante, Rob Voigt, Dora Wang, Linda Waugh, Bonnie Webber, Robb Willer, Dekai Wu, Mei Hing Yee, Courtney Young, Linda Yu, Samantha Zee, Katja Zelljadt, Daniel Ziblatt, and Arnold Zwicky.

SAN FRANCISCOS MOST EXPENSIVE restaurant wont give you a menu. Well, thats not strictly true. The attentive staff will happily offer you a beautifully printed list of dishes (trout roe, sea urchin, cardoon, brassicas...)by email, after you get home, as a souvenir. Saison, this marvelous Michelin-starred restaurant, isnt alone. Expensive restaurants everywhere increasingly offer blind tasting menus in which you dont know what youre going to eat in each course until the plate is set down on your table. When it comes to high-status restaurants, it seems that the more you pay, the less choice you have.

Status used to be expressed a different way. If you ate out in the 1970s Im sure you dined at one of those establishments that writer Calvin Trillin called . Trillin, an early supporter of local and ethnic eating, mocked pretentious restaurants whose menus were as macaronic a mishmash of French and English as their names (macaronic: from a sixteenth-century verse style mixing Latin with Italian dialect originally named, as well see, after macaroni). Trillin complained of being led to a purple palace that serves Continental cuisine and has as its chief creative employee a menu-writer rather than a chef.

Menu writing manuals of the day advised restaurants to sometimes even just the French article Le with an otherwise English sentence:

Flaming Coffee Diablo, Prepared en Vue of Guest

Ravioli parmigiana, en casserole

Menus full of macaronic French werent just a fad. Through the wonder of the Internet, we can go back in time more than a century in the New York Public Librarys :

Flounder sur le plat

Eggs au beurre noir

Fried chicken a la Maryland half

Green turtle a langlaise

Sirloin steak aux champignons

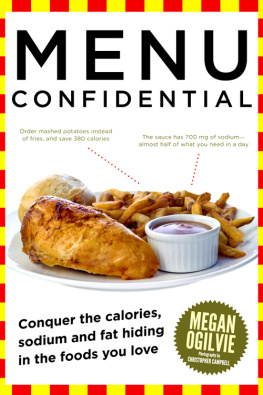

Were not in the 1970s any more (let alone the 1870s), and now this kind of fake French just seems amusing to us. But status and social class never really go away; modern expensive restaurants still have ways of signaling that they are high-status, fancy places, or aspire to be. In fact, every time you read a description of a dish on a menu you are looking at all sorts of latent linguistic clues, clues about how we think about wealth and social class, how our society views our food, even clues about all sorts of things that restaurant marketers might not want us to know.

What are the modern indicators of an expensive, high-class restaurant? Perhaps youll recognize the marketing techniques in the descriptions of these three dishes from pricey places:

HERB ROASTED ELYSIAN FIELDS FARMS LAMB

Eggplant Porridge, Cherry Peppers,

Greenmarket Cucumbers and Pine Nut Jus

GRASS FED ANGUS BEEF CARPACCIO

Pan Roasted King Trumpet Mushrooms

Dirty Girl Farm Romano Bean Tempura

Persillade, Extra Virgin Olive Oil

BISON BURGER

8 oz. blue star farms, grass fed & pasture raised,

melted gorgonzola, grilled vegetables

You probably noticed the extraordinary attention the menu writers paid to the origins of the food, mentioning the names of farms (Elysian Fields, Dirty Girl, blue star), giving us images of the ranch (grass fed, pasture raised), and alluding to the farmers market (Greenmarket Cucumbers).

And menu writers arent the only ones to get carried away. In the first episode of the show Portlandia Fred Armisen and Carrie Brownstein, obsessive locavores, question the provenance of the chicken at a restaurant. The waitress tries to reassure them that the chicken is a heritage breed, woodland raised chicken that has been fed a diet of sheeps milk, soy, and hazelnuts. Armisen and Brownstein, still unsatisfied (The hazelnuts, these are local?) head out to visit the farm where the chicken was raised just to make sure.

Next page