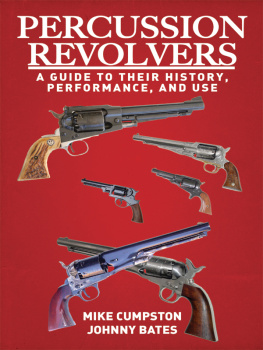

Copyright 2014 by Michael E. Cumpston

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62873-695-3

E-book ISBN: 978-1-62914-035-3

Printed in China

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

The authors recognize the contributions and assistance of James Austin, Living History authority; Leo Bradshaw Jr., author and arms collector; A. K. Church, writer/epistemologist; Dr. Robert Corwin, arms collector and Civil War historian; Don Eichenberger of Clarksville Gun and Rod; Gatofeo-The Ugly Cat, able researcher; Jim Taylor, writer and vintage firearms expert; Kirk Wiseman, writer; and the authors listed in the bibliography. Karl Erich Martell, attorney and firearms right advocate, provided major assistance with editorial preparation.

Production numbers of the pistols and revolver models come from various sources. In compiling this book we relied heavily on: R. L. Wilson, Colt, An American Legend ; P. L. Shumaker, Variations of the Old Model Pocket Pistol 1849 to 1872 ; Lt. Col. Robert D. Whitting III, The Colt Whitneyville-Walker Pistol .

We owe much to the readers of our first volume, Percussion Pistols and Revolvers: History, Performance, and Practical Use , who have identified avenues for further investigation and provided assistance in the form of test materials and personal insight. Their acceptance of the first work is largely responsible for our own continued enthusiasm and the publication of this book. Michael T. Gemind, Billy Fugett, Steve Oppermann, and Ron Brown helped materially in broadening the scope of the present work. Jeff Johns, editor of GUNS Magazine, by publishing our articles and encouraging us to tell it like it is, contributed to our knowledge base and defrayed many of the attendant expenses.

Introduction

Sixteen years after the standardization of the percussion cap, at a time when the contemporary armies depended on flintlock firearms, Samuel Colts revolving arms became the first practical repeaters. The earliest revolvers came into being in the production modalities of the Iron Age, and then drove the development of assembly line mass production interchangeable parts and the use of power machinery that would define the industries of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The manufactories of Colt and Eli Whitney Jr. gave rise to the role of skilled and semiskilled labor within the assembly line environment. The revolver was a key artifact in this defining era of history, contributing to the spread of Western culture and practically demonstrating democracy. It granted personal empowerment at a time when, while the individual was the common denominator in the social contract, reality was that free people often had to take up arms to assert that ideal. The Gun Culture that arose with the coming of the first revolvers frustrated the social planners and Utopians. Now, a century and a half later and fifty years beyond the Civil War centennial that brought them back into the public consciousness, the original guns and their replicas remain popular among collectors, shooters, and students of history.

Samuel Colt developed his first percussion revolvers in the early 1830s and began producing them in 1836. Dynamic development continued into the 1860s, and the revolvers stayed in general use until the middle 1870s with the widespread availability of metallic cartridge revolvers. In examining the percussion revolvers within their historical context, it is useful to divide this short era into three convenient segments.

The Early Period extends from 1836 until 1848, with the Paterson and Walker revolvers representing the bulk of development. During this time, the Colt patents covered several essentials of the revolving handguns and long arms. Early examples of both developed at the same rate.

Between 1849 and 1855 was a realistic Middle Period, where the basic and simplified single-action mechanism came to full development. Colt had distributed his revolvers across the Western world and much of the Orient and Africa. Some of the European patents had expired, and competing companies entered their own revolver designs. A flirtation with self-contained metallic cartridges began with the development of the Lefaucheux Pin Fire revolvers.

In the Later Period, from the late 1850s through the 1860s, Colts American patent extension no longer afforded even a domestic monopoly. Consequently, innovations such as the double-action revolvers, already popular in England and the European continent, came into full development, and competitive designs appeared on both sides of the Atlantic. Long arms had advanced beyond the evolution of the revolver, and practical metallic cartridge arms were coming into use. Revolver development was at a temporary standstill because Smith & Wesson owned the Rollin White patent to the through-bored cylinder and had an effective monopoly on breechloading cartridge revolvers. In the late 1850s, Smith & Wesson began producing small-caliber pocket revolvers chambered for the .22 and .32 rimfire cartridges, but they did not develop full-sized metallic cartridge revolvers until the end of the 1860s.

While revolver developers awaited the expiration of the Rollin White patent, percussion revolvers benefited from developments in the mass production of steel of consistent, controlled quality. The latter Colts were stronger and lighter than those made from the earlier processes, and designs by Remington, Adams, LeMat, and others benefited as well.

So, within this rough chronology, we examine the revolvers with particular attention to those available as modern replicas, shooting characteristics, routine maintenance, and such modifications as were applied to the originals in keeping with the practice and technologies of the times. Load selection and methodology are consistent with historical practices, with performance data extracted from shooting modern blackpowder, the substitutes, and currently available components. We explore availability of the spare parts and after-sale support necessary to keep the modern replicas up and running. Diverging from our primary interest in the designs and practices of the 19th Century, we also examine recent innovations in percussion revolvers and evolving shooting modalities.

The historic vignettes deal with the actual use of the arms within their historical framework. We present the stories and legends with the assumption that they are true. Of course, we do so with the full understanding that many of them are no more than the oft-repeated pronouncements of would-be experts, gun industry hucksterism, and journalistic flapdoodle. In other words, our stories are the constituent ingredients of history books, modern news reports, and politicians autobiographies. Strict historical accuracy is illusive. In studying the available literature, we encounter many variations and contradictions. On rare occasions, direct observation casts doubt upon the literal truth of written history. Climb the Enchanted Rock in central Texas, and you will find no crevasse or redoubt where Jack Hays might have taken refuge to pick off advancing Comanches. The top of the dome is a moonscape that would hardly conceal a rabbit. Hays either took his stand out in the open or encountered his adversaries on the boulder-strewn fringes of the Medicine Rock.