F rankly, I was not sympathetically inclined, a year or so ago, to the proposal to write a book about INEOSs first twenty years. It had undertones of self-indulgence written all over it, it risked being a hostage to fortune, and, if one is at all superstitious, then telling the world publicly how wonderful we have been over two exciting decades has all the hallmarks of the kiss of death!

So, no, I wasnt enthusiastic. Nor were John and Andy, my two colleagues and lifetime friends.

So how come the U-turn? Did vanity ultimately win the day?

Here I struggle a little. We John, Andy and myself have enjoyed a most extraordinary twenty years, which has seen INEOS grow from a small obscure chemical company in Antwerp to, quite frankly, a colossal enterprise today. Now we have chemical plants the size of the City of London. We have over 100 chemical sites worldwide. We have annual sales of $60 billion, comparable to the GDP of a medium-sized country. We produce 50 million tonnes of chemicals and 50 million tonnes of oil and oil products. We own 1 billion barrels of oil still in the ground. We have eight tankers shuttling shale gas from America to Europe. We have a car company, a clothes company and a football club, not to mention my hotel business. Its difficult to keep up sometimes. Last year every single business in INEOS beat its budget. Our safety record is genuinely world-class. Profits hit $7 billion in 2017.

So, is the story worth telling? Who knows? But John, Andy and I were lobbied persistently and, ultimately, we weakly relented.

To accomplish what we have in such a short timeframe requires taking some risk. We have experienced some strong headwinds on our journey (some might say cyclonic is a better description!) and many moments are indelibly seared into memory. All of this will, hopefully, make interesting reading.

There has never been a dull moment. It has been an absorbing time and tremendous fun, in the main. We weathered the crisis in 2008, no thanks to Gordon Brown, but our ship was close to foundering. We stood our ground with the unions in Grangemouth four years ago and, ultimately, saved Grangemouth and many thousands of jobs. Today, Grangemouth is tremendously successful, but it teetered for weeks on the verge of closure. And we brought US shale to Europe, whose stubborn refusal to entertain such a cost-effective energy source threatened the whole European chemical industry when oil was over $100 per barrel. Exciting times. Although I admit it has been exciting in a manufacturing sense. I was born in the heart of industrial revolution territory and I suppose it runs in my blood. I believe we benefit if we actually make some of the goods we buy rather than just sell services. And, just as importantly, much of the northern economy in Britain depends on manufacturing jobs which today are few and far between. Britain has its own rust belt, as America did before its shale revolution resolved a lot of that. Im optimistic we could do the same here.

Its traditional to offer thanks in such a book as this, and INEOS has cause to be grateful to many people who helped it along the way, but we certainly wouldnt be where we are today without John Reece and Andy Currie. Both clever chaps from Cambridge, unlike like my humble red-brick, they share my northern values, hailing from Sunderland and Doncaster grammar schools respectively. We work closely together. We almost always reach a consensus when important decisions come our way and, likewise, they both enjoy good humour. Northern values include hard work, good manners, grit, rigour and an essential sense of humour, with wit as a bonus. Life is short!

My family, I am told, has endured the occasional bout of grumpiness from my direction I am sure only on a microscopic level and exceedingly infrequently but has given much support and helped keep my feet firmly planted on the ground. The family always come first, and we make this message clear throughout INEOS.

I am fortunate in that I can switch off, so family holidays offer a real rest. My father once said that there is little point worrying about things you can do nothing about. It was good advice.

So, for better or worse, here follows the tale of INEOS.

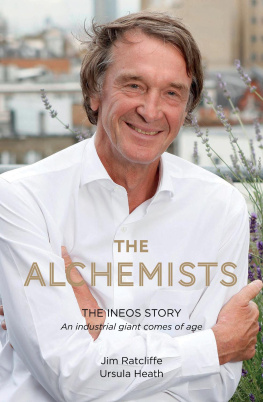

Jim Ratcliffe

April 2018

P rofessor Sir Andrew Likierman was dean of London Business School between 2009 and 2017. Educated at the University of Vienna and Balliol College, Oxford, Andrews career has spanned the public and private sectors as well as many years in academic life. In the public sector he has been an official in the Cabinet Office and the Treasury, non-executive chairman of the National Audit Office, and a director of the Bank of England among other posts. Roles in the private sector include director of Barclays plc and non-executive director of Times Newspapers. Andrew taught Jim Ratcliffe during his MBA at London Business School in 1978.

There is something irresistible about the story of a plucky upstart making good. Even better, this story is real life. And in an entrepreneurial world dominated by services and high-tech, INEOS is a sighting of that rarest of birds, the highly successful UK manufacturing entrepreneur.

Theres always a danger of companies writing their own stories, as Jim frankly acknowledges. This is also a story still very much in the making, with major developments in recent years including building a fleet of tankers in China to bring US shale gas to the UK, buying North Sea oil fields and pipelines, and planning and public opinion permitting fracking. More are on the way.

But even if its mid-story, there are good reasons to tell it. INEOS is now a force in international petrochemical and energy supply, including the North Sea. Its operations in Scotland alone make it a significant national player. But as a private company it has to provide less information than those that are listed and this book gives a context for those who want the background to INEOS. The company is also proud of what it has achieved, and wants to share where it comes from and what it has done. Then there are some real insights for those wanting to learn from others, and understand what it takes in terms of risks and rewards, inspiration and perspiration, to turn dreams into reality.

The obvious question from a success story of this magnitude is: why INEOS, and why not so many of the hopefuls who started at the same time, full of enthusiasm, most of whom will have failed? While each start-up is different and each entrepreneur has his or her own strengths and weaknesses, there are certainly some lessons from INEOS for tomorrows aspiring entrepreneurs to think about, including those a world away from manufacturing.

First, there is the combination of technical and managerial professionalism. The management team are a group who understand their fields and can apply their knowledge and experience. The combination of detailed technical knowledge with professional management has been crucial in overcoming challenges to build the business. All too often a great idea fails because there are not the management skills to turn it into a viable enterprise and it isnt an accident that, contrary to so many other cases, a high proportion of INEOS acquisitions have been successful. The logic of acquiring underperforming assets has been backed up by the skills and ability to make them perform. But while the basis of the companys fortunes has been turning the oil majors unloved chemical plant into highly profitable operations, the lateral moves to other energy fields in recent years show that the professionalism is not confined to making the original concept work.

Another key factor is the advantage that has come from continued private ownership. This is most evident in two contradictory aspects of speed: the ability to take decisions quickly, combined with the opportunity to be patient without being pushed by the capital markets. It is also clear that these freedoms have come at the cost of increased risk that comes with reliance on debt in troubled times.