Donkey

Animal

Series editor: Jonathan Burt

Already published

Crow

Boria Sax Ant

Charlotte Sleigh Tortoise

Peter Young Cockroach

Marion Copeland Dog

Susan McHugh Oyster

Rebecca Stott Bear

Robert E. Bieder Bee

Claire Preston Rat

Jonathan Burt Snake

Drake Stutesman Falcon

Helen Macdonald | Salmon

Peter Coates Fox

Martin Wallen Fly

Steven Connor Cat

Katharine M. Rogers Peacock

Christine E. Jackson Cow

Hannah Velten Swan

Peter Young Shark

Dean Crawford Rhinoceros

Kelly Enright Moose

Kevin Jackson Duck

Victoria de Rijke | Ape

John Sorenson Pigeon

Barbara Allen Owl

Desmond Morris Snail

Peter Williams Hare

Simon Carnell Penguin

Stephen Martin Lion

Deidre Jackson Camel

Robert Irwin Pig

Brett Mizelle Vulture

Thom van Dooren Lobster

Richard J. King |

Whale

Joe Roman Parrot

Paul Carter Tiger

Susie Green | Horse

Elaine Walker Elephant

Daniel Wylie Eel

Richard Schweid |

Donkey

Jill Bough

REAKTION BOOKS |

|

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2011

Copyright Jill Bough 2011

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by Eurasia

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Bough, Jill

Donkey. (Animal)

1. Donkeys 2. Donkeys History.

3. Donkeys Symbolic aspects.

I. Title II. Series

636.182-DC22

eISBN: 9781861899873

Contents

Introduction

He can live without man. But man can scarcely do without the labour, the sacrifice, the suffering of the donkey... that has accompanied man since the dawn of time, in all weathers, humbly and patiently serving the most brutal of all animals.

Donkeys are commonplace. They live in most areas of the world alongside humans, an integral presence in many cultures. Even if they are no longer useful to human endeavours in much of the developed world, they are still pulling carts in Africa, bearing heavy loads in India, carrying tourists in Greece and taking children for rides along British beaches. Considering how long they have been domesticated and how valuable they have been in human history, we know remarkably little of their lives or their stories, or even of their welfare. It is not that they are unfamiliar; it is that they are generally considered beneath notice. As they crossed the world in the service of their human masters, donkeys have been among the most used, and abused, animals in history.

Donkeys have served humans, largely as beasts of burden, since the time of their domestication, possibly 10,000 years ago.

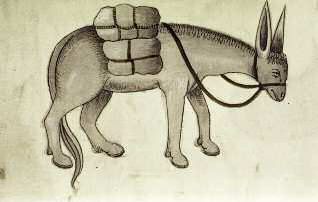

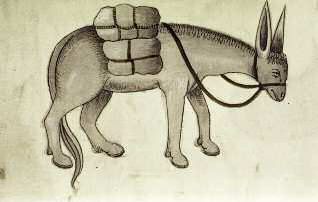

| Illustration of a donkey with a pack-load, c. 1520s. |  |

It is estimated that there are 41 million donkeys in the world today, 51 per cent in Asia, 28 per cent in Africa and 18 per cent in Central and South America. A report from the Food and Agri culture Organization (FAO) in 2006 revealed that donkey populations were continually diminishing globally despite the animal being the main form of transport in many parts of the developing world. Although ignorance and prejudice with regard to the value of donkeys remain in many areas of Africa today, mainly because of the implications of lack of progress because of the animals lowly and backward status, experts in animal traction consider donkeys to be one of the best draught animals. They are reported to have the longest working life, to be able to work in the driest areas, to manage on the least food, to be the least disease-prone, to be able to work at variable speeds and to have a high learning ability by comparison to horses, mules and oxen.

However, despite the service that donkeys have rendered to humans in all ages and societies, they have received little recognition in return. The injustices and indignities they have received

| Francisco de Goya, Tu que no puedes from the Caprichos series, 17978. |  |

However, I maintain that it arises from both what the actual animal, the donkey, is and does and, perhaps even more im portantly, from how we choose to represent donkeys in human terms (or humans in donkey terms); the language used to de scribe them usually involving demeaning comparisons, as will be ex plained in the following paragraphs. The words donkey and ass both refer to the domesticated animal descended from the wild asses of Africa: their origins, history and physiological attributes will be considered in chapter One. Donkeys are hardy and resilient animals that can work tirelessly with littlemaintenance. Although usually slow paced, they are steady and sure-footed. They are also strong and sturdy and can carry heavy burdens relative to their size. They are, for example, often expected to carry loads equal to two-thirds or more of their body weight, as has been recorded in Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela, Greece, Tunisia, Spain and throughout most of Africa. Although known as good workers, donkeys have a strong sense of self-preser vation, which has influenced their repu tation for stubbornness.

The origins of the name donkey are not clear, and have changed over time and with context. In the language of their early owners, the Semites, donkeys were called anah and inLatin asinus (which later became ane in French). The etymology confirms that donkeys were established throughout the Mediterranean, Levantine and Anatolian regions long before Indo-European horse users arrived. The derivation of the word donkey to describe the domesticated ass is not really known but it is suggested that it could be from dun, or dull grey-brown coloured, and the form perhaps influenced by the word monkey. A male donkey is called a jack and a female a jenny or jennet. In parts of the United States where Latin American culture persists,