I should like to thank warmly many people, including the following.

My valued doctoral thesis supervisors at the Institute of Archaeology UCL, Dr. Louise Martin, Professor David Wengrow and Professor Stephen Shennan, and my honorary supervisors Professor William Clarence-Smith of SOAS and Dr. Harriet Crawford of UCL, who helped me out of holes into which I fell. At the Institute of Archaeology, I would particularly like to thank Professors Ruth Whitehouse, Sue Hamilton and Dr. Marion Cutting for their support, as well as the anonymous academic reviewers, and at Routledge Matt Gibbons, Kangan, Louise, Deborah and all the production team. I also fully acknowledge the role of my PhD examiners Professor Paul Halstead of the University of Sheffield and Dr. Mark Altaweel of the Institute of Archaeology.

The late Professor Andrew Sherratt, whom I was privileged to call my friend and upon whose shoulders I hope to stand.

A range of donkey-friends including Professor Paul Starkey, Dr. Peta Jones, Ed Emery of the Donkey Conference, and Professor Haskel and Dr. Tina Greenfield. Also Dr. Carol Palmer at the British Institute in Amman, Dr. Jaafar Jotheri, Dr. Abubakar Suleiman, Nasser Kalawoun and Melissa Upjohn.

For my Burkina Faso research visit in 2013, my friend Bettie Petith of FITIL and in Burkina Faso my friends and colleagues Robert Ilboudo, Bako Bazoin and Alphonse Hien. For my Ethiopia research visit in 2014, Stephen Blakeway, and the Donkey Sanctuary team in Addis Ababa and Bahir Dar, particularly Dr. Bojia Endebu, Dr. Asmamaw Beyene, Anteneh Kassa and Dr. Tewodros Tesfaye Mekonnen.

For both research visits, I would like to thank the UCL Doctoral School and the Institute of Archaeology for their important contributions to the funding of my research visits, and additionally the British Institute in Eastern Africa for their generous grant towards funding my Ethiopian visit.

On illustrations, kind help has been given in particular by Harriet Pottinger and others at the Donkey Sanctuary, The Brooke, Sue Sherratt, Ronika Power, Frank Frster and Dr. Rudolph Kuper, Rick Hauser, Dan Potts, the late Lamia al-Gailani, Ianir Milevski, Ann Searight, Noah Snyder-Mackler, Galen Frysinger, Bruno at http://theonearmedcrab.com and HarperCollins. Neil Thomson and John Downie gave me invaluable technical help on image resolution, line-drawings and other illustration difficulties.

Some of the photos of present-day working-animal use in this book are of imperfect quality, included nevertheless because they valuably record fast-disappearing lifeways and practices. This applies in particular to my own photos from my fieldwork trips to Burkina Faso and Ethiopia, at a time when I had no idea that a book would result; I apologise for all their failings.

Glossary of selected terms

| Reference | Explanation |

|

| Cattle | I refer to cattle genencally, and also specifically to oxen (castrated males) and cows (this always indicates the female of the species). See Chapter 3.1 for notes on taurine and zebu cattle |

| Donkeys (wild and domesticated) and onagers | Equus, briefly for the purpose of this work, today comprises horses (E. ferus caballus and the related E. ferus przewalski), donkeys (E. asinus), zebras (various types including the quagga) and hemiones (E. hemionus, with various geographically differentiated branches including the onager, kiang and kulan, some rare or extinct). The different Equus species can interbreed but normally produce sterile offspring, as with the horse/donkey mule. In studies on the Ancient Near East, E. hemionus is commonly termed both 'hemione' and the more region-specific 'onager'; I generally use the latter term. There are some uncertain hypotheses as to the existence of a small equid, E. hydruntinus, possibly related to the hemione or zebra, inhabiting the mid-Levant and Anatolia but extinct since the early Holocene. E. asinus is descended from Nubian and (probably to a lesser extent) Somalian clades; truly wild versions are almost extinct (Geigl and Grange 2012:89). Some commentators elaborate the donkey species as the wild E. africanus and domesticated sub-species E. africanus asinus, but in view of the well-evidenced continued close blending of wild and working donkeys throughout history, I continue with the overall term E. asinus. Similarly, while certain commentators label non-domesticated versions as 'ass' or 'wild ass' and domesticated ones as 'donkey', I and others consider 'ass' and the more modern term 'donkey' as synonymous, and I use the latter term throughout. |

| Semi-wild (as in Chapters 4.3, 5.1 and 6.1) | I use this term for donkeys which have lived freely in the wild in a region over perhaps hundreds of years, long ago shedding associations with the circumstances of their original introduction, but which have become familiar over time with human groups co-living in the region, who may 'collect' them and use them ad hoc for transport. This term differs from 'feral', which applies to escaped domesticated animals and their immediate offspring |

| Trypanosomiasis | A disease affecting cattle and donkeys, endemic to parts of Africa, carried by tsetse flies |

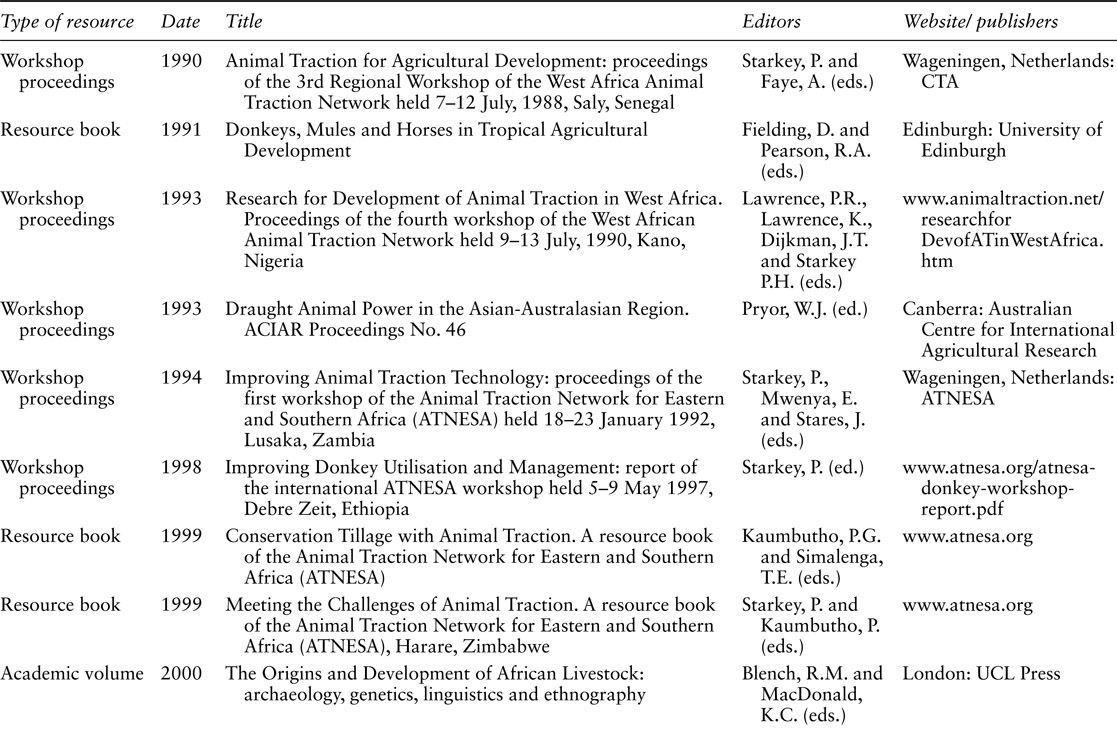

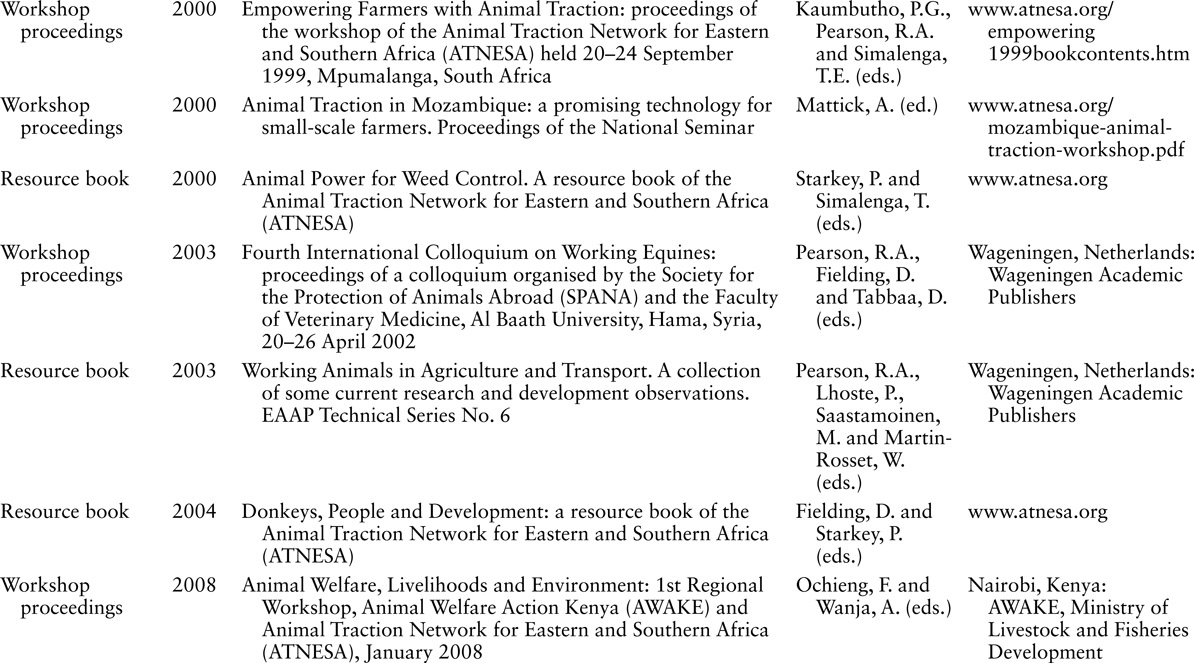

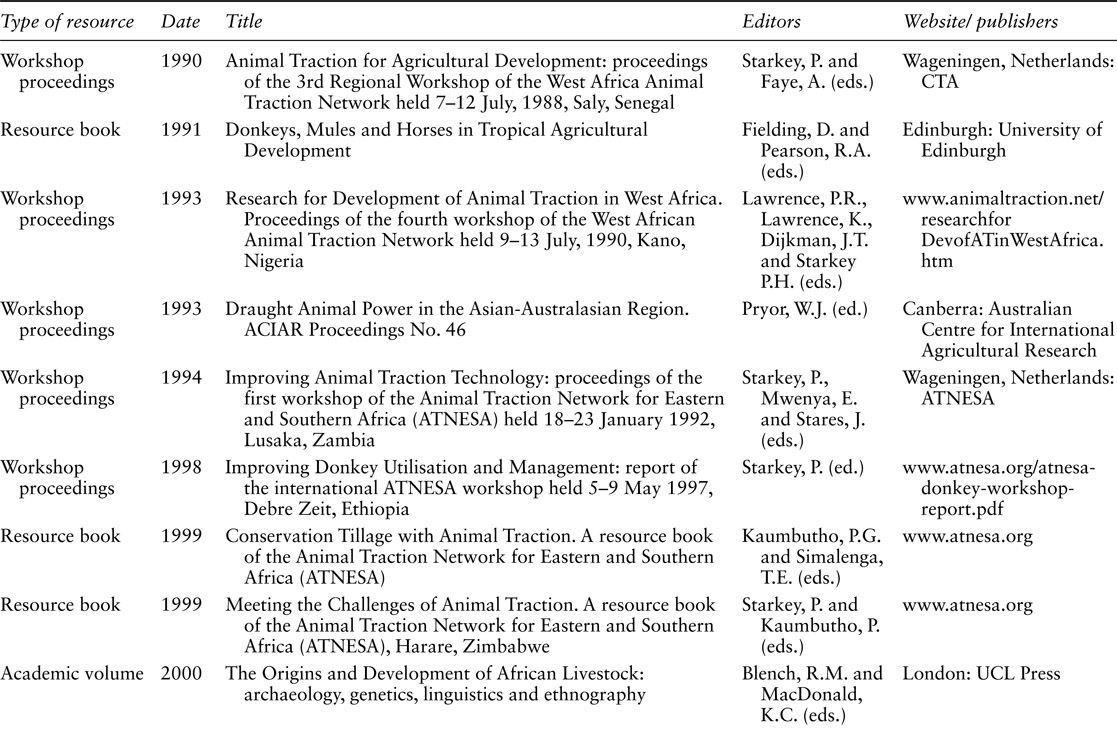

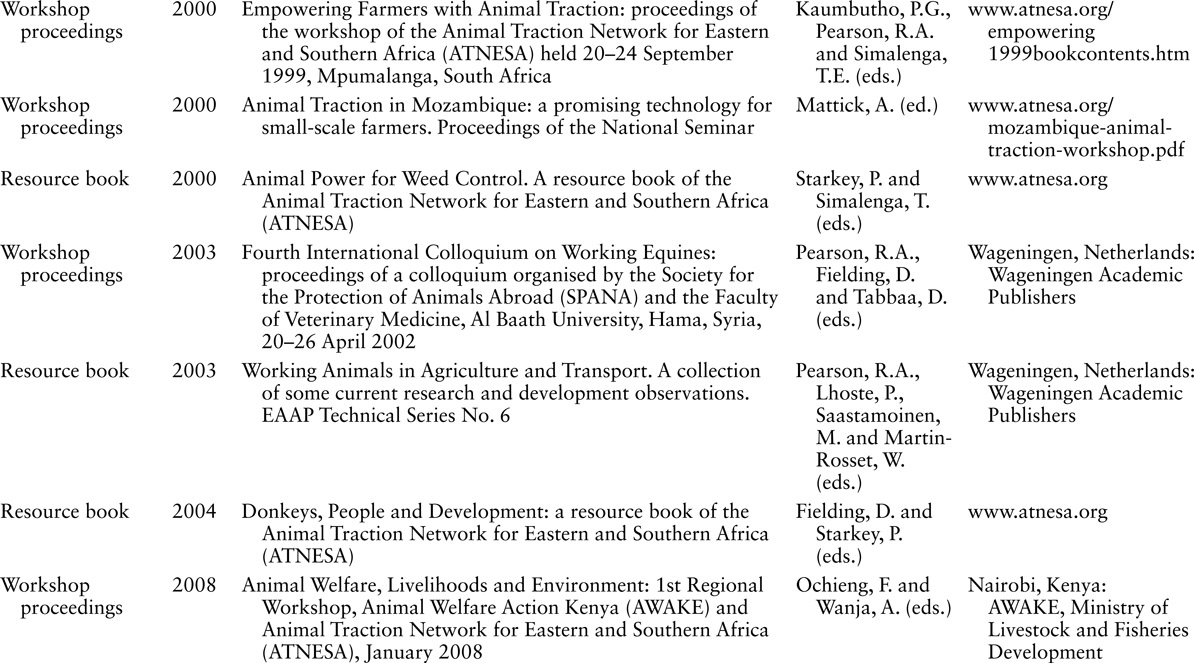

For this book and its preceding PhD thesis, I have analysed in detail 389 modern studies and surveys of working-animal use in developing regions far too many to reference and list in full in my bibliography alongside the many archaeological sources, though I include all directly referenced modern sources. I describe my data-set of modern development studies in detail in Chapter 1.2, and as an indication of the genre and context of many of my sources, I list in (by date) selected key NGO, official and academic volumes, each containing multiple useful individual papers.

Many of the surveys and studies consulted come from workshop proceedings and resource books sponsored by the Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA), who were very active until the early 2000s. Their website (.

Some key modern development-study volumes

Adams, R.McC. (1981). Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Adams, R.McC. (2008). An interdisciplinary overview of a Mesopotamian city and its hinterlands. Cuneiform Digital Library Journal 1, 111.

Adams, R.McC. (2010). Slavery and freedom in the Third Dynasty of Ur: Implications of the Garshana archives. Cuneiform Digital Library Journal 2, 18.

Admassu, B. and Shiferaw, Y. (2011). Donkeys, Horses and Mules: Their Contribution to Peoples Livelihoods in Ethiopia . Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: The Brooke.

Admiralty War Staff (1916). A Handbook of Mesopotamia. Vol. 1: General . London: Admiralty War Staff Intelligence Division.

Algaze, G. (2001). Initial social complexity in Southwestern Asia: The Mesopotamian advantage. Current Anthropology 42, 199233. DOI: 10.1086/320005.

Algaze, G. (2008). Ancient Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Civilization: The Evolution of an Urban Landscape . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Alhaique, F. (2008). Faunal remains. In: Nigro, L. (ed.) Khirbet al-Batrawy II: The EB II City-Gate, the EB II-III Fortifications, the EB II-III Temple: Preliminary Report of the Second (2006) and Third (2007) Seasons of Excavations . Rome: La Sapienza, 32758.