1992, 1994 J.N. Postgate

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Postgate, J. Nicholas

Early Mesopotamia: society and economy at the dawn of history.

I. Title

Postgate, J.N.

Early Mesopotamia: society and economy at the dawn of history/Nicholas Postgate.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. IraqCivilisationTo 634. 2. IraqEconomic conditions.

I. Title

This book is dedicated to the people of Iraq.

The need for this book was brought home to me on my return to Cambridge in 1981 to succeed Margaret Munn-Rankin in the teaching of ancient Near Eastern history and archaeology. The archaeology of Mesopotamia had always formed part of the first-year course for all archaeology students, but there was no single book which exploited Mesopotamias special advantage the opportunity to combine documentary and archaeological evidence. The book therefore sets out to describe an early state in terms sufficiently broad for the general reader, but with enough detail to help the specialist and to convey the wealth of information still to be recovered. The result is more history than archaeology, but my intention has been to bring the two disciplines closer together, and this is reflected in the number of illustrations: there are far more of these than originally intended, but they imposed themselves on the text as it proceeded. Quotations from the cuneiform sources are treated in the same way as illustrations so as to unclutter the narrative. The translations have all been compared with the original text, although I have often borrowed them with few or no changes from the previous translator.

A glance at the bibliography will convince the reader that detailed study of ancient Mesopotamia requires a knowledge of German and French, but after each chapter I have recommended a few titles, mostly in English, which would serve to take the reader more deeply into the issues.

In writing this book my principal debt has been to Professor Marvin Powell, who read the majority of the text in draft, suggested improvements to style, substance and accessibility, and saved me from a number of serious howlers. I am very grateful to him for giving unstintingly of his time and his expertise.

Professor Peter Steinkeller advised and corrected me on points of detail in the translation of some of the texts, for which I am very grateful, as I am to Jean Bottro, Tina Breckwoldt, Jean-Marie Durand, Peter Laslett and Roger Matthews for answering questions and supplying information.

I am greatly indebted to many colleagues who have freely offered help with illustrations, whether by supplying them or by giving permission to use them, or often both: to Professor R. McC. Adams, P. Amiet, Professor John Baines, Professor Dr R.-M. Boehmer, Dr A. Caubet, Dr Dominique Collon, David Connolly, Dr G. van Driel, Professor Jean-Marie Durand, Dr Uwe Finkbeiner, Dr Lamia al-Gailani, Dr L. Jakob-Rost, Professor Wolfgang Heimpel, Dr Bahijah Khalil Ismail, Dr Stefan Kroll, Professor Jgen Laesse, Professor Jean-Claude Margueron, Dr Roger Matthews, Helen McDonald, Dr Roger Moorey, Professor Raouf Munchaev, Professor Paolo Matthiae, Professor Hans Nissen, John Ray, and contributing to its interpretation, and to Elizabeth Postgate for help with drafting work. My thanks also go to the staff at Routledge: to Andrew Wheatcroft, and to Hilary Moor, Jill Rawnsley and Liz Paton for dealing very efficiently with a difficult manuscript. Finally, my thanks go to Trinity College, Cambridge, for support in various forms, including a grant towards the cost of gathering and reproducing the illustrations.

This book would not have been possible if I had not lived in Iraq. I would like to record my lasting gratitude to the modern inhabitants of Mesopotamia for their constant courtesy and hospitality, in homes and offices, in city and countryside, and in times good and bad.

Note to paperback edition: a few factual errors and misprints have been corrected, and some additional references added to the Notes and Further reading. My thanks to Bendt Alster, Rainer Boehmer, Tina Breckwoldt, Jerrold Cooper, Stephanie Dalley, Igor Mikhailovich Diakonoff and Dietz Edzard for pointing out mistakes and suggesting additions.

J.N. Postgate

1991, 1994

In the transliteration of cuneiform texts certain conventions are used. The letter is the equivalent of English sh; is the emphatic s encountered in Akkadian and other Semitic languages. In cases where the distinction is needed, bold face is used for Sumerian, italics for Akkadian words. Square brackets [] enclose portions of a text which are missing on the original hut have been supplied in translation. When citing Sumerian I have dispensed with the diacritics used by specialists, except in a few cases where it seemed desirable to retain them.

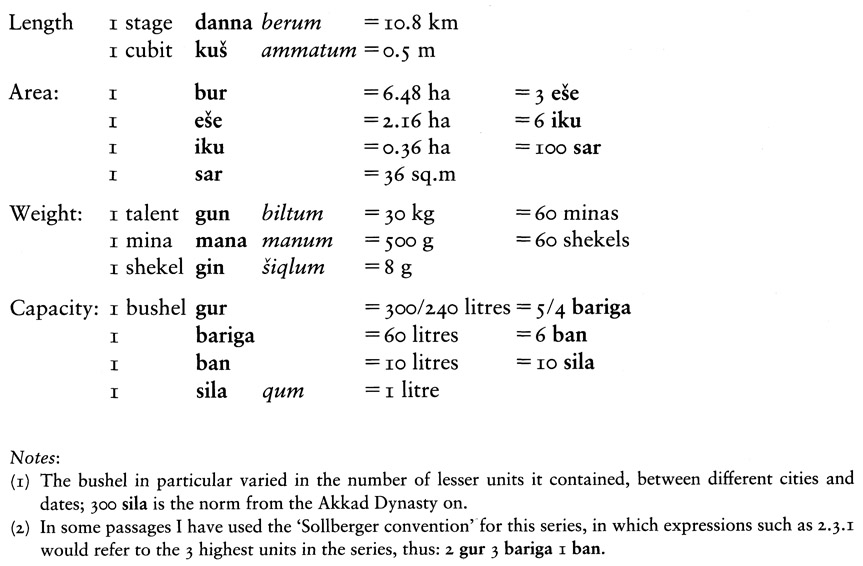

The metrology of Mesopotamia is enormously complex, but in citing cuneiform documents some measures of weight, volume, etc. cannot be avoided. I have not adopted a rigid approach since (as explained in the Epilogue) there is no attempt to broach the quantitative aspects of the record. Nevertheless, the following list with approximate modern equivalences may be helpful to the reader. The tables are deliberately restricted to measurements used in the text; for the details of the complete systems see Powell 1989.

The history of the western world begins in the Near East, in the Nile Valley and in Mesopotamia, the basin of the Tigris and Euphrates. Here two contemporary but strangely differing cultures served as the centres from which literate civilization radiated. Egypt, physically constrained within the narrow strip of the Nile Valley and isolated from western Asia, retained its highly idiosyncratic identity with little infusion from elsewhere, and did not export its language or script or other artistic forms, except upstream to Nubia. Mesopotamia was open along both flanks to intrusion from desert and mountain, and its cuneiform script was exported across thousands of miles and adapted to a great variety of languages. The record of the early stages of these two formative cultures also comes to us in different shapes: most of the early records surviving from Egypt are formal texts with a ceremonial or religious content, and much of our knowledge of their life comes from the superb detail of the tomb paintings. For Mesopotamia very little pictorial evidence has survived, but the durability of the clay tablet has given us enormous sheaves of written detail about the organization of early society.