PENGUIN BOOKS

MESOPOTAMIA

Gwendolyn Leick is an anthropologist and Assyriologist. She lectures in Anthropology at Richmond, the American International University in London and in Design Theory and History at Chelsea College of Art and Design. She also acts as a cultural tour guide in the Middle East, lecturing on history, archaeology and anthropology. She is the author of various publications on the Ancient Near East, including A Dictionary of Near Eastern Mythology, Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature and Who's Who in the Ancient Near East.

Gwendolyn Leick

MESOPOTAMIA

THE INVENTION OF THE CITY

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11, Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published by Allen Lane The Penguin Press 2001

Published in Penguin Books 2002

Copyright Gwendolyn Leick, 2001

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-192711-4

Contents

List of Illustrations

(Acknowledgements are given in parentheses)

Preface

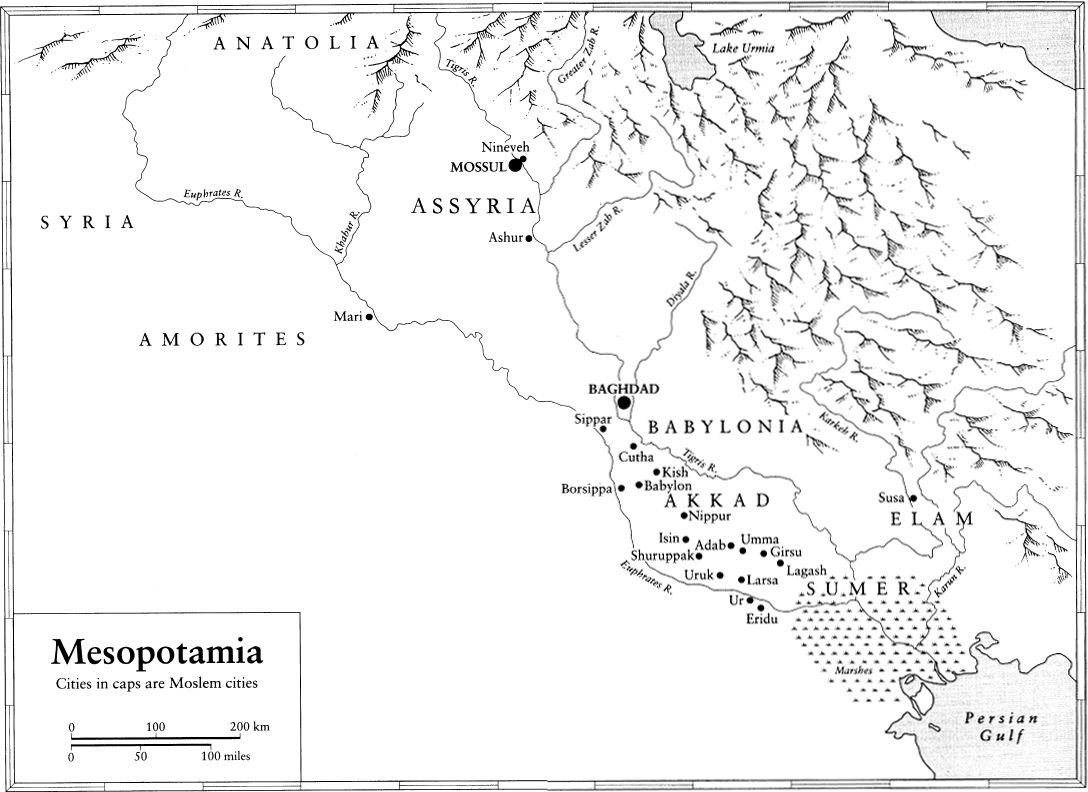

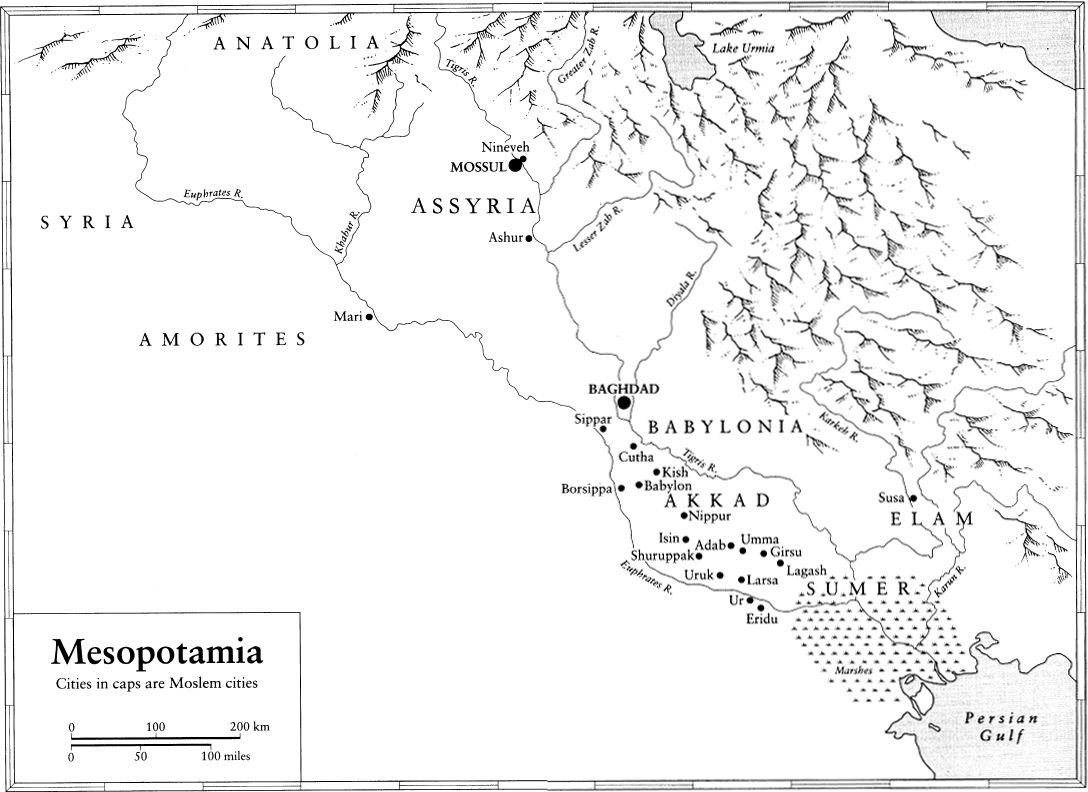

Mesopotamia is the name the ancient Greeks gave to a land corresponding approximately to present-day Iraq. It means literally between the rivers, referring to the Tigris and the Euphrates, which rise in the mountains of Anatolia to flow in more or less parallel courses down to the Persian Gulf. In contemporary usage, Mesopotamia has acquired a broader meaning, referring not just to the land between the two main rivers but also to their tributaries and valleys, so describing an area that includes not only Iraq but also eastern Syria and south-eastern Turkey. Its natural borders are formed by the mountain ridges of Anatolia to the north, the Zagros range to the east, the Arabian desert to the south-west and the Persian Gulf. Within this geographical context are two distinct zones, the first being the zone north of present-day Baghdad, where the Tigris and Euphrates come closest together. This is the area often called the Fertile Crescent, a stretch of land that runs from the Mediterranean coast to northern Iraq and benefits from the rainfall generated by the chain of mountains extending along the Syrian coast and southern Anatolia. To the south of this belt of hills and valleys stretches the Arabian desert. It was in the climatically favourable Fertile Crescent that the first human settlements and the beginnings of agriculture and animal husbandry originated some 10,000 years ago.

The second zone, between Baghdad and the Persian Gulf, is essentially a vast flood plain, the land having been formed by huge deposits of silt carried down by the rivers. This alluvial soil, with its high and varied mineral content, is potentially highly fertile, but the land is flat and there are no mountains to generate rain. Only after man had learnt to adapt to this environment, significantly through control of the waterways by means of canals and dykes, did it become possible to capitalize on the inherent economic potential of the southern plains. It was only then that the first large-scale communities began to develop, in which people began to profit from a system beyond subsistence to produce a surplus, diversify their cultural activities and live in increasingly large numbers in a new form of collective community, the city.

The invention of cities may well be the most enduring legacy of Mesopotamia. There was not just one but dozens of cities, each controlling its own rural and pastoral territory and its own system of irrigation. But since these communities were strung along the main waterways like so many pearls on a necklace, they had to arrive at forms of cooperation and mutual tolerance. Historians have tended to highlight the emergence of centralized states which exercised control over often extensive territories, but the most enduring and successful socio-political unit to emerge in Mesopotamia remained the city state.

This book seeks to tell the stories of ten Mesopotamian cities in a way that will do justice to this urban paradigm. The individual stories are heterogeneous, reflecting the often contradictory thoughts and conclusions of the archaeologists who have interpreted the physical evidence of sites, of the epigraphists and Assyriologists who have copied and translated the cuneiform tablets, of the historians, geologists and anthropologists who have considered the findings. Most importantly, each city tells its own story through its discovery and a gradual understanding of its historical development set beside how the Mesopotamians themselves wrote about it, what it was known for and which gods resided in its temples.

The collection of narratives concerning ten Mesopotamian cities that follows runs in a roughly chronological sequence from fifth-millennium Eridu through to Babylon, which lasted into the first few centuries AD . Each city has a place in a reality that has been reduced to an archaeological site in Iraq, more or less robbed of its secrets, more or less buried under sand-dunes. Each site has variously yielded its riches, from statues and potsherds to cylinder seals and jewellery, brick walls and tablets. Sheer accident of discovery has determined what has been found, whether it is palace archives or graves, temples or huts, a whole library from a period covering some thirty years or the architectural sequence for a temple spanning two millennia. What has been made of all these tangible bits and pieces is a further dimension, subjected to trends in intellectual fashion and the need to revise interpretations in the light of new findings and new ideas.

I have picked out some of these strands and ideas as one picks up sherds on a mound and used them as props to tell my narratives. The cities had their own interpreters, the scribes and savants of their time, so we will certainly hear their voices, however stilted they may sound in the awkward style of Assyriological translation. Overall, a multitude of voices should emerge of archaeologists and epigraphists, of ancient kings and their spin-doctors, of theologians ancient and not so ancient, of anthropologists and temple bureaucrats, of Babylonian businesswomen and divorcees. All these various strands of narrative have produced a different pattern for each city. But like some very old remnant of a beautiful fragment of textile, this reconstructed fabric of the past must be full of holes and badly worn parts that can never be restored or mended. Nevertheless the different fragments should allow us to build an impression of the richness and complexity of the original civilization that produced them.

Next page