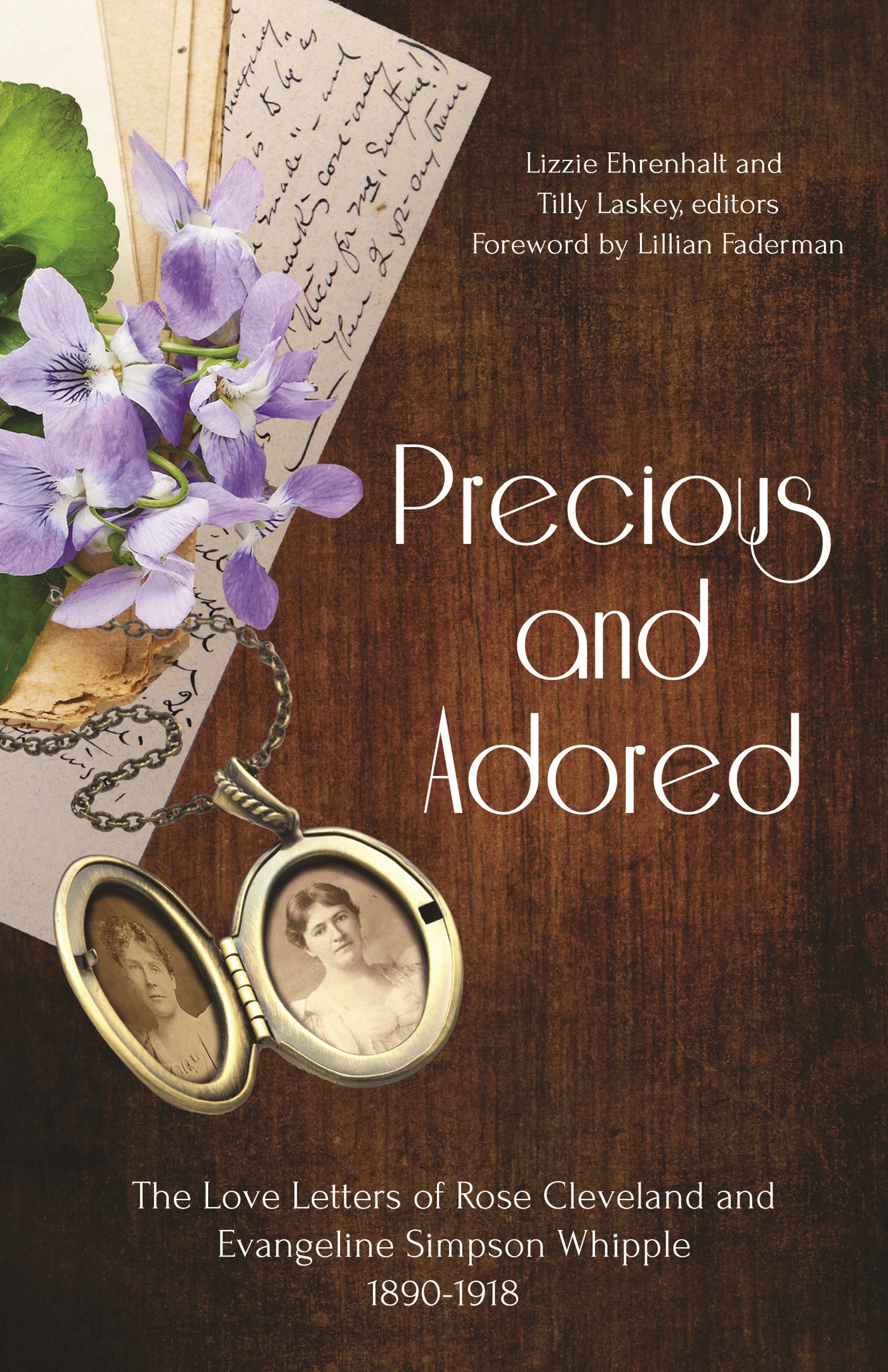

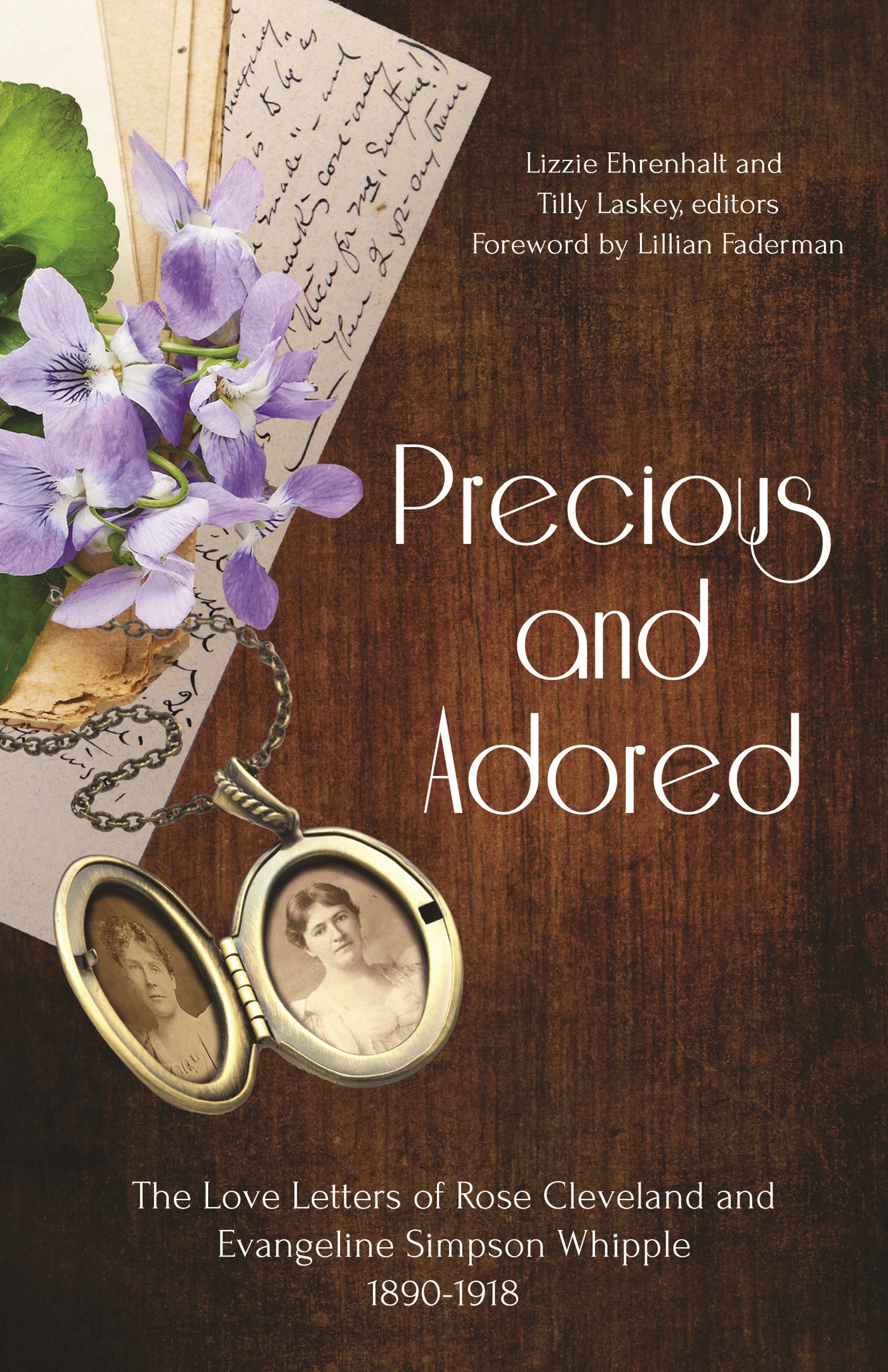

Precious and Adored

Precious and Adored

The Love Letters of Rose Cleveland

and

Evangeline Simpson Whipple, 18901918

EDITED BY

Lizzie Ehrenhalt and Tilly Laskey

The publication of this book was supported though a generous grant from the June D. Holmquist Publications and Research Fund.

The publication of this book was also supported, in part, with a gift from an anonymous donor.

Copyright 2019 by Lizzie Ehrenhalt and Tilly Laskey. Other materials copyright 2019 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 551021906.

mnhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN: 978-1-68134-129-3 (paper)

ISBN: 978-1-68134-130-9 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cleveland, Rose Elizabeth, 18461918, correspondent. | Ehrenhalt, Lizzie, 1982 editor. | Laskey, Tilly, 1966 editor. | Whipple, Evangeline Simpson, 18571930, correspondent.

Title: Precious and adored : the love letters of Rose Cleveland and Evangeline Simpson Whipple, 18901918 / edited by Lizzie Ehrenhalt and Tilly Laskey.

Description: St. Paul, MN : Minnesota Historical Society Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018060568 | ISBN 9781681341293 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781681341309 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Cleveland, Rose Elizabeth, 18461918Correspondence. | Whipple, Evangeline Simpson, 18571930Correspondence. | LesbiansUnited StatesCorrespondence. | LesbiansUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC HQ75.3 .C54 2019 | DDC 306.76/630973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018060568

This and other Minnesota Historical Society Press books are available from popular e-book vendors.

Book design and typesetting by Judy Gilats

Contents

by Lillian Faderman

Foreword

Lillian Faderman

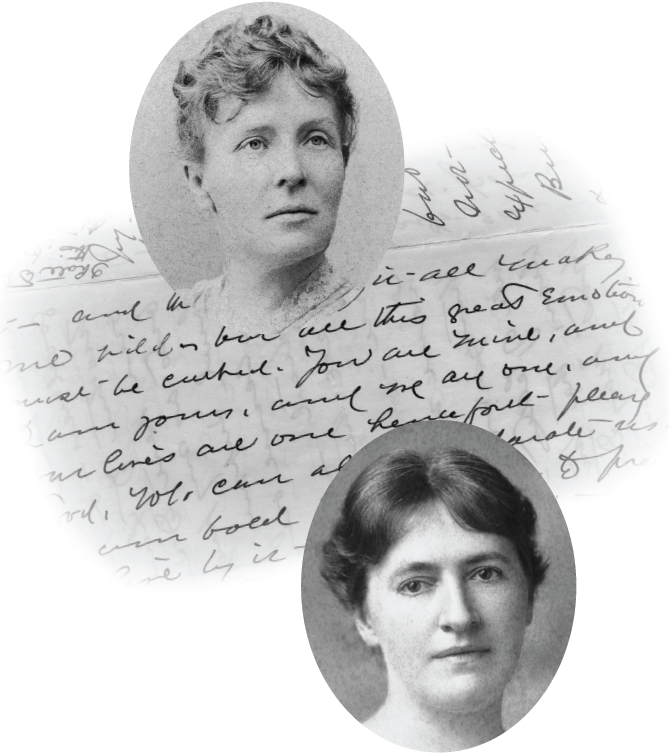

IN SPRING 1890, Rose Cleveland, sister of US President Grover Cleveland, wrote in a letter to Evangeline Marrs Simpson, a wealthy widow whom she had come to know that winter, My Eve! Ah, how I love you. It paralyzes me. You are mine by every sign in Earth & Heaven, by every sign in soul & spirit & body. Sweet, Sweet, Rose declared in another letter, I dare not think of your armsbut I am coming to them. The sexual intensity in her letters to Evangeline is a humanizing revelation about the possibilities of womens lives in her day. They belie the image her contemporaries cherished of unmarried upper-class ladies as decorously and tranquilly nonsexual. In one sexually playful letter, for instance, Rose poignantly laments the passing spring and her passing youth, and she implores Evangeline to restore them both to her through their erotic intimacy: Will it come again, Eve? Is it keeping for me? Are you keeping it for me, wrapped up warm and sweet, fresh and deep, all in a closed bud that will openwhen? Make me believe it, Evegive me a writingsign or seal and deliver it to me as your bond or your pound of fleshand I will have both. That Evangeline reciprocated Roses sexual intensity we can glimpse through the occasional bits of her letters that are preserved by Roses quoting them. Oh, darling, come to me this night, Evangeline wrote, my Clevy, my Viking, MyEverything, Come!

Roses love for Evangeline continued for almost three decadesthrough their erotic passion; through the shock, six years into their relationship, of the forty-year-old Evangelines marriage to Minnesotas seventy-four-year-old Episcopal bishop Henry Whipple; and through Rose and Evangelines gradually renewed intimacy after the bishops death five years later. Evangeline and Rose finally left America permanently and settled together in Italy, where they lived until Roses death in 1918. Evangeline, who died in 1930, chose to be buried in Italy, too, beside the woman she loved. The letters in Precious and Adored re-create this story of one of the most remarkable love relationships between women in American history. Lizzie Ehrenhalt and Tilly Laskey have done scholars as well as general readers a great service in gathering these letters and providing indispensable context for them through thoughtful and informative introductions and skillful annotations.

The Victorian era, when Rose and Evangeline came of age, assumed that proper women were passionless, that they would perform their conjugal duties if married because that was obligatorybut left to their own devices they were devoid of desire. Rose and Evangeline are not the only stunning proofs of that fallacy. There are numerous extant examples of women among their contemporaries who penned similarly fervid letters to another. For example, Mamie Gwinn, future professor at Bryn Mawr College, wrote to M. Carey Thomas, Bryn Mawrs future president, My love, my little big lovetis 11:30 but I am awake and longing for you. I lie on the sofa and dont undress because I am a coward and miserable undressing without you. Mary Woolley, the president of

Rose Cleveland never put a name to her love for Evangeline in her letters. If they had been a middle-class professional couple like the women mentioned above, their relationship might have been described as a Boston marriage. The term signified a committed long-term domestic relationship between two career women, though the erotic possibilities generally went undiscussed by the outside world, the word marriage notwithstanding.

But wealthy women of leisure such as Rose and Evangeline could not be seen as having chosen a Boston marriage over wifehood for the reason that they wished to be engaged in a profession. Though Rose and Evangeline were deeply involved in social betterment activities, they never concerned themselves with working for their livelihood. Nor could they claim, as many middle-class professional women in same-sex relationships did, that shared quarters were a practical convenience for them. Rose and Evangeline each owned several homes and often lived separately. Boston marriage could not describe their commitment to one another, nor did they need to explain away their relationship by that term: their class and wealth shielded them from the vulnerabilities of prejudice that middle-class professional women might have feared.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.