CONTENTS

To my wife, DeAnne, my best friend and biggest support,

and

to those with whom I have shared the rope in Patagonia:

Jim Donini, Alex Hall, Stefan Hiermaier, Charlie Fowler, Thomas Ulrich, David Fasel, Stefan Siegrist, Boris Strmsek, J. Jay Brooks, Pablo Besser, Waldo Farias, Robyn Bunch, Steve Schraeder, and Andrs Zegers.

This would not have been possible without you.

Chief among these motives was the overwhelming idea of the great whale himself. Such a portentous and mysterious monster roused all my curiosity. Then the wild and distant seas where he rolled his island bulk; the undeliverable, nameless perils of the whale; these, with all the attending marvels of a thousand Patagonian sights and sounds, helped to sway me to my wish. With other men, perhaps, such things would not have been inducements; but as for me, I am tormented with an everlasting itch for things remote. I love to sail forbidden seas, and land on barbarous coasts.

HERMAN MELVILLE, Moby-Dick.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to all the editors who have worked with me and my Patagonian writings: especially DeAnne Musolf Crouch, who has been there through all of it; Lee Boudreaux at Random House (this project has been lucky from the get-go); Steve Roper, Allen Steck, and Ed Webster at Ascent; Joan Tapper at Islands; Oliver Payne at National Geographic; Alison Osius and Jeff Achey at Climbing; and George Bracksieck and Dougald MacDonald at Rock & Ice; and to Robert Legault for his diligent copyediting.

To Ronald Goldfarb, my dream agent, who does exactly what he says hes going to do when he says hes going to do it, and the first person besides DeAnne to share my vision for Enduring Patagonia.

All those with whom Ive climbed in Patagonia deserve special thanks. We kept one another safe, did some radical stuff, and made it down from some of the worlds most wild places.

To Rolando Garibotti, for friendship and inspirationno man on earth knows more about the mountains of Patagonia.

To Thomas Ulrich, Charlie Fowler, and Jim Donini, for access to their photo collections.

To my many friends in Chaltn: Susana Queiro, the soul of Argentinas Parque Nacional de los Glaciares, and her husband, Ricardo Sanchez; Roxana Arbilla of Piedra del Fraile (a good chunk of my first draft was written there); Javier Maceira, Rodrigo Mazzola, Gabriel Fassio, Mariana Hardoy, Patricia Barra, and Sandra Maigua of Rancho Grande (where I wrote the other great chunk of my first draft); Anabel Machiena and Mariana Villanueva of La Chocolatera; Marcelo Pagani and Doctora Carolina Cod of El Pilar; Andrea Neelsen, Pablo Cottescu, and Ana Queija of La Ruca Mahuida; Mirta Levi and Ral Cardozo of La Casita; Rubn Vzquez and Ester Havermanns of the Albergue Patagonia; Iv Domenec of La Senyera and Estancia Canig; Miguel Burgos of La Boticueva; Don Rodolfo Guerra and his wife, Isolina Ogrizek; Max O'Dell; Marcela Antonutti; Gerardo Javier Spisso; Hernan Salas; Alberto del Castillo; Horacio Cod; and Mara Ines Leyenda of Estancia Maip.

To Kevin Trenberth of the National Center for Atmospheric Research for helping me understand the weather processes of the Southern Hemisphere. Any mistakes included herein are mine and mine alone.

So many others deserve thanks: Franci Novak, Thomas Kocar, Silvana Albano, Adriana Albano, Luis Roberto Albano, Lojze Kocur, Jani Kocmur, Stanko Hrovat, Janko Vidmar, Soames Floweree, Silvo Karo, Jos Luis Fonrouge, John Bragg, Jon Krakauer, Tom Strickler, Brian Lipson, Jenny Mathew, Viju Mathew, and Mr. Mathew, Kent McClannan, Bruce Miller, Doug Byerly, Jimmy Surette, Forrest Murphy, Yvon Chouinard, Miyazaki Motohiko, Athol Whimp, Andrew Lindblade, John Fantini, Simon Parsons, the Zegers family of Santiago, Ross Johnson, Michele Hanson, Greg Corliss, Phil Krichilsky, Mary Beth Krichilsky, Frank Macon, Brian Coppersmith, Nelly Avila, Marta Conforti, Dani and Mari and Emmanuel Alonso, Joseph Conrad, Antoine de Saint-Exupry, and Beryl Markham.

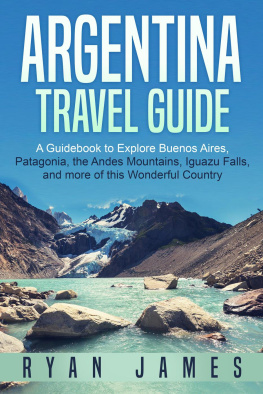

MY PATAGONIA

An otherworldly range of mountains exists in Patagonia, at the southern end of the Americas. It is a sublime range, where ice and granite soar with a dancers grace. From the mountains feet tumble glaciers and dark forests of beech. The summits float in the southern sky, impossibly remote. Climbers who gaze upon these wonders ache to unlock their secrets. Hard, steep, massive, these might be our planets most perfect mountains.

To court these summits is to graft fear to your heart, for all is not idyllic beauty among the great peaks of Patagonia. They stand squarely athwart what sailors refer to as the roaring forties" and furious fifties"that region of the Southern Hemisphere between 40 and 60 south latitude known for ferocious wind and storm. The violent weather spawned over the great south sea charges through the Patagonian Andes with gale-force wind, roaring cloud, and stinging snow. Buried like a rapier deep into the heart of the southern ocean, Patagonia is a land trapped between angry torrents of sea and sky.

The horrendous weather more than makes up for the fact that the mountains of Patagonia do not count extreme altitude as a weapon. Altitude is only one aspect of climbing difficulty. The enormous walls of Patagonia demand fast, efficient, and expert practice of every climbing technique. Wealthy dilettantes cannot buy their way onto these exclusive summits. Only years of dedication to the alpine trade earn a climber the right to gain a Patagonian summit.

Cerro Fitzroy and Cerro Torre are the two crown jewels of the range. Seen from across the wind-swept scrub of the steppes to the east, they are the two crux battlements in the long Andean rampart. Far outdoing the Great Pyramids, Fitzroys stone bulk towers 10,000 feet over the arid plains and dominates the landscape like a barbarian king. Beside and a bit behind the king rises Cerro Torre, his royal consort, a graceful obelisk: tall, slender, vertiginous, elusive, hers the very form of alpine perfection. Although Fitzroy is a few hundred feet taller, Cerro Torre exceeds the king in every aspect except sizein difficulty, in threat, in promise, in beauty, in subtlety, and in the savageness of her fury. Cerro Fitzroy and Cerro Torre shoulder the sky like titans.

Cerro Torre stands at the left end of a line of towers, all divided from Fitzroy and his satellites by a deep valley and a flowing glacier. Fitzroys half-dozen satellites form a horseshoe to the left and right of the king. Anywhere else, the peaks that flank Fitzroy and Cerro Torre would be centerpiece summits; here in Patagonia they are the palace guard.

Beyond the mountains to the west lies the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap. The ice cap runs north-south like a long irregular cigar, bounded on one side by the front range of the Andes, and on the other by the Pacific Ocean. At its widest point, twenty-five miles north of the Fitzroy massif, the ice cap is almost sixty miles across. At its narrowest, sixty miles south of Fitzroy, less than ten miles of ice separate the Pacific Ocean in Fiordo Peel from fresh waters that flow into the Brazo Mayor (the major arm) of Lago Argentino. From north to south the ice cap is 225 miles long, and without counting the many glaciers that drain it, the surface of the ice cap measures more than 5,000 square miles. It is our worlds largest nonpolar expanse of ice and one of the least knowable landscapes on earth. From no point in the settled world can one get a true impression of the ice cap, for the Andes block the view of it from the inhabited desert to the east. There are places from which we can observe the glaciers that drain the ice cap through breaks in the mountain chain, and from other points we can view bits and pieces of the ice fields, but the ice cap itself exists almost in myth, in a world beyond men. No man makes his home there, and only the most intrepid access this frozen fastnessand even they cannot stay for long.

Next page