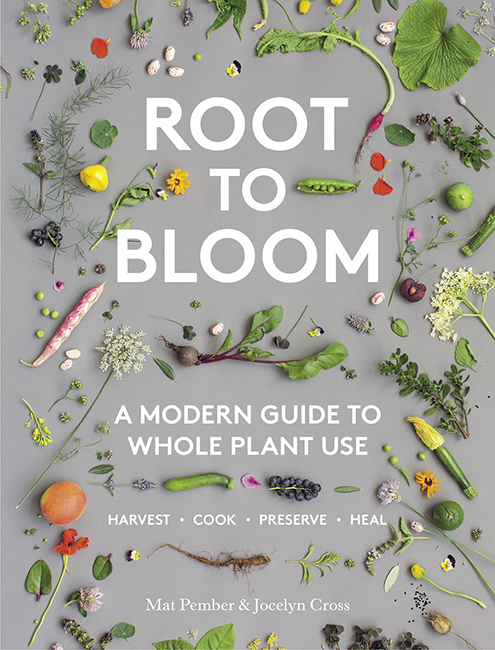

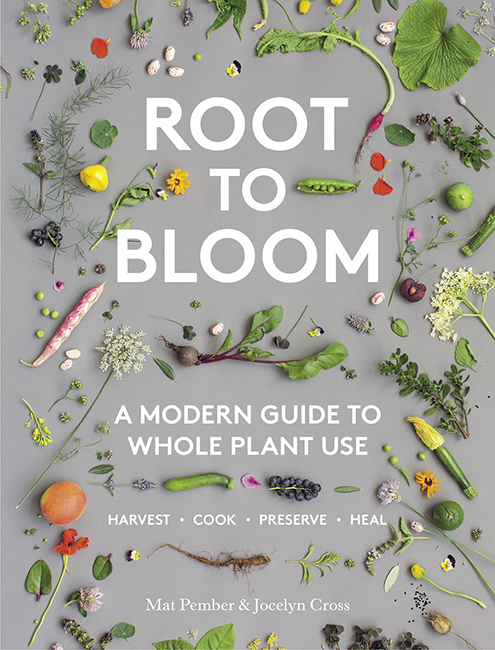

Edible parts of a plant

ROOT  | STEM  | LEAF  | FLOWER  | FRUIT  | SEED  |

To think of coriander as a leaf is to think of a pig as bacon; its only one of its many parts. This Homer Simpson form of tunnel vision (mmm, bacon) means we miss out on all the other delicious parts of plants that have only recently come to be regarded as waste. We are growing lots of perfectly edible food, then wasting most of it. Most disturbingly, the practice is so ingrained in us, that we are doing it in our gardens too.

Our perspective of what is food and what is waste is perhaps a by-product of a farming industry that for too long has been striving for efficiency in business rather than the efficient use of our resources. Plants that are grown exclusively for their fruit, foliage or seeds typically have many more edible parts. There are some exceptions, such as the nightshade family, which has poisonous flowers and foliage, but most plants, be it coriander, dill, peas or nasturtiums, are full of food, from the root all the way to the bloom.

As we understand more about the earths limited resources, we must also revaluate our notion of resourcefulness. Resourcefulness has always been the cornerstone of our evolution. It is not a new idea. Recycling and composting, for example, are essential practices that have been around since the caveman killed his first beast, ate it almost entirely, made a coat out of the skin, used its bones for jewellery, then fed the rest to livestock and vultures who, in turn, fertilised his sprawling veggie patch.

From the wild greens that then flourished would have come edible flowers, too.

From this, came nose-to-tail eating, and it remains prevalent in almost every culture. It is standard practice among the Italian members of my family and, even though the Australian half may seem out of touch, their Scottish ancestors certainly feasted on an offal-rich haggis or two. Recently, there has been a revival of nose-to-tail eating in the restaurant world, and it is often marketed as something new and sustainable. However, using the whole animal is an age-old concept, and the same can be said for using all parts of an edible plant.

When it comes to fruit, vegetables and herbs, we desperately need to revise our perspective of edibility. Both growers and consumers have become stuck on the idea that food is what we get at the supermarket, which is to say it is limited and uniform. Apparently it has to be, because we dump almost as much food as we eat because it is too long or too short, too skinny or too fat; in fact, too anything other than perfect. And what about the other parts of these plants? The wasted bits that are perfectly edible but arent valued by modern society? So many edible parts of common plants are needlessly discarded.

It is easy to become focused on the primary growth of our plants at the expense of everything else, but, as growers and consumers, it only takes a small aperture in our thinking to open up a world of culinary possibilities. For this reason, we want to bring back root-to-bloom eating.

Plants have so much to offer all the way from the root to the bloom. Coriander, for example, is a completely edible plant. While we tend to favour its leaf foliage, it also produces sweet and pungent flowers, powerful-tasting stems and root matter and, of course, sought-after seeds, which are one of the most versatile spices in the pantry.

Most plants present an opportunity to harvest before and after their primary growth, which means we neednt wait months to enjoy the spoils of our labour. It also means that even if we fail to grow that trophy pumpkin, the rest of the plant has not gone to waste. By enjoying the whole plant, we experience a whole new spectrum of flavour and texture that would otherwise end up in the compost bin.

The concept of root-to-bloom eating is something we continually strive to live by. Similar to the public consciousness of wasting unwanted parts of an animal in favour of more desirable cuts, we cant stand to see edible parts of a plant going to waste. More than that, we want to celebrate the sense of connection that growing and eating all parts of a plant gives us.

Exploring other parts of a plant is like peeling back layers from an onion; its revealing. And while root-to-bloom eating isnt anything new, we think it should make a comeback, because when a plant and a gardener go to so much effort to grow something together, no part of it should be wasted.

Root vegetables and rhizomes are some of our oldest and most nutritious cultivated vegetables. Their use dates back 8,000 years or more, both for culinary and medicinal purposes. The use of some varieties, such as beetroot and turmeric, has even diversified beyond food and medicine to being used for natural fabric dyes.

As with many other vegetables, various root vegetables have been identified as aphrodisiacs throughout history. The Greek name for carrot, philtron, means love charm, and beetroot derives its colour from a compound called betalain, which helps our body create sex hormones.

Growing underground, root vegetables and rhizomes have the most immediate access to the soils nutrients. Root vegetables prefer cooler soils that help to convert their starches into sugars, while rhizomes prefer consistent warmth, otherwise lying dormant in cold conditions. Like a hibernating bear with only a few reserves in its belly, rhizomes have tough cellular walls and a powerful build-up of starches, which they use as fuel to help get them through the cool season.

Although the root is the ultimate prize, the foliage of just about every root vegetable and rhizome is edible too. Beetroot greens are commonly used in salads and are nutritionally comparable to kale and silverbeet. Carrot greens are tender and palatable and make a good substitute for parsley, while the foliage of ginger and turmeric is more plentiful than the rhizome itself.

Ginger leaves, for example, have a peppery flavour that is milder than the rhizome but more prolific, providing extra produce to cook with as the ginger root develops below. It also has the highest anti-cancer effect as stated by the United States National Cancer Institute.

Daucus carota

Next page