ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Firstly, sincere thanks to those who have knitted my designs for many years, and for knitting the garments in this book superbly. I could not do any of it without them. Knitters: Joan Brown, Betty Cottle, Betty Dobson, Tina Fenwick Smith, Angie Harris, Janet Hawkins, Barbara Jarman, Margaret Maher, Margaret Malony, Kneale Palmer, Paula Parker, Clare Sampson and Yvonne Tatters.

Invaluable practical help came from the pattern checking party: Teresa MacLeod, Emma Vining, Rosemary Reeves, Sue Modgridge, Maggie Mockeridge, Kim Blair and Joy Shenton.

Weavers and colleagues Ann Richards and Deirdre Wood have given support in collaborating on our soft engineering textiles project. The creative discussions on technique-led design have reinforced my ideas for this book.

Unknowing contributors from whom I have learnt a huge amount while teaching courses and workshops are students who have helped me find better ways of explaining and communicating my approach. There is always an exchange of ideas and techniques, whether international, traditional or invented, which all go towards understanding how knitting works.

Thanks also to loyal customers who have contributed more than they can know by demonstrating not only appreciation, but how designs work (or dont work) on different bodies, and have provoked thoughts for new designs.

Colin Mills has once again found imaginative ways of displaying and photographing the work with glowing results. Thanks to Kelly-Anne Levey for her elegant design.

Lastly, thanks to Dan for his continuing patience and support.

INTRODUCTION

Designing gives you an understanding of the craft far deeper than a whole lifetime of pattern copying can achieve.

Montse Stanley, Knitting Your Own Designs for a Perfect Fit (1982)

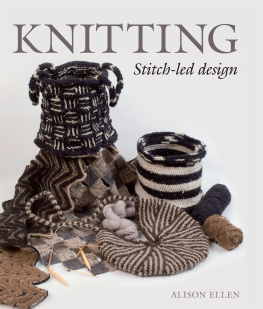

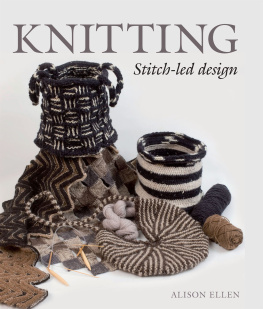

Knitted textures.

We are in danger of taking knitting for granted. We think we know what we can produce and what to expect: we know it can make jumpers that are thick and warm or fine and lacy, cabled or Fair Isle-patterned. But just imagine if you had never come across this technique before, and especially if you had never followed a pattern. Imagine a technique you dont know. If you were shown a weaving loom, or methods of knotting, netting, weaving braids or any way of making a textile that you had not seen before, it would be strange and intriguing: it would look immensely complicated and skilled, and you would need to spend time learning and experimenting before you could see the creative possibilities. This book approaches knitting in this way, by taking a fresh look at our old familiar friend, which, even though it has been part of our lives for a few hundred years, offers us extraordinary and untapped freedom in creativity. Stepping away from readymade patterns and taking time to explore the technique may open doors to ideas for new ways of using and developing it.

There is a formal structure to knitting; an orderliness and symmetry of rows of loops made by a continuous thread travelling horizontally, the loops or stitches lying above each other in vertical columns. Working one stitch at a time in rows, they fall from the needle, facing one way (knit) or the other way (purl). But - and this is the key - working one stitch at a time gives the freedom to manipulate and juggle these stitches so that as well as producing a neat, ordered textile, the fabric can swell and buckle, grow and bulge from the inside, as well as being shaped at the edges by increasing and decreasing the numbers of stitches. This growth and movement can be organic, growing, curving and swirling in a way similar to the growth of plants, and working by hand enables us to sculpt the fabric in a very free way, breaking the bounds of the formal structure. Also, knitting by hand offers the chance to work freely and intuitively. We can change our mind as we go. It could be argued that there is a better chance of success with some sort of a plan before we start, and it does help to know roughly what size we are aiming at; but even so it is good to know the opportunity is there to change our minds and improvise as well.

Following knitting patterns does not encourage this way of thinking; to enable creativity, we need to step away from the usual instructions in the well-known shorthand K1, P1, psso language of the knitting pattern where one works blindly row by row towards a finished object. It needs something one never has enough of time to pause and take a fresh look, and time to explore and experiment.

This book looks in minute detail at how stitches can change the knitted fabric, using even the simplest combinations of knit and purl to alter its surface, feel and drape, and it goes on to show how it can be constructed not just from the bottom working towards the top, but can begin at any point, edge or corner, or from the centre and be worked outwards.

Two knitting authors, Mary Thomas and Elizabeth Zimmerman, wrote books that many years ago got me thinking by explaining the inner workings of the knitted structure, and encouraging the question what happens if ? This is the question to use when approaching knitting, and hopefully, even if it is not always answered, if repeated enough, it will encourage further exploration.

What is knitting?

Knitting doesnt have to be a jumble of confusing words and shorthand to be followed blindly, nor does it have to be blanket squares or baby clothes, or the kind of knitting that has given us knitters a bad name. With a bit of experimenting and understanding of the effects of different stitches it becomes a creative textile technique with enormous possibilities. Even a square piece of knitting can be shaped very simply; it can grow organically from the centre as well as the edge, and can be manipulated into any flat or sculptural shape.

Knitting has had a lot of derogatory press in the past, perhaps especially in the UK, and even with recent new movements in knitting there are still remnants of the old disparaging attitude. Is this because it is considered easy? Many different crafts involve repetitive movements that become automatic so they may look simple or mindless, and its easy to forget the level of skill that is developed over many years of working at a craft. Busy hands free the makers mind, so its possible to talk and listen while making. From the makers point of view, there is skill involved, comfort in repetition and satisfaction in creativity: the hands are busy and the mind is free. Both the creative process and the resulting garment can lift your spirits.

How knitting is made

When we think of knitting, the typical fabric that comes to mind is stocking stitch, or stockinet. Think T-shirt fabric, and you have it: smooth on one side, rougher on the other, and stretchy. Most of all, it is comfortable. How did we ever live without knitted fabric?

Words can be misleading. Although the term stockinet or stockinette is used in some countries, in Britain it has a different contemporary meaning: a smooth cloth used for making undergarments; not really the appropriate terminology for what we are after here. As I am writing in British-English, the term stocking stitch will be used throughout to describe this basic fabric we all recognize.

Sometimes this book will be stating the obvious: we all know how stocking stitch is made. However, these thoughts and observations are included as a way of stepping back from the usual view of knitting, to snap us out of the idea that we have to follow instructions, and to begin a process of thinking creatively.

Next page