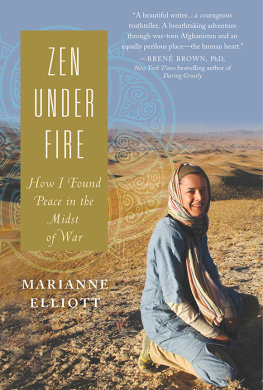

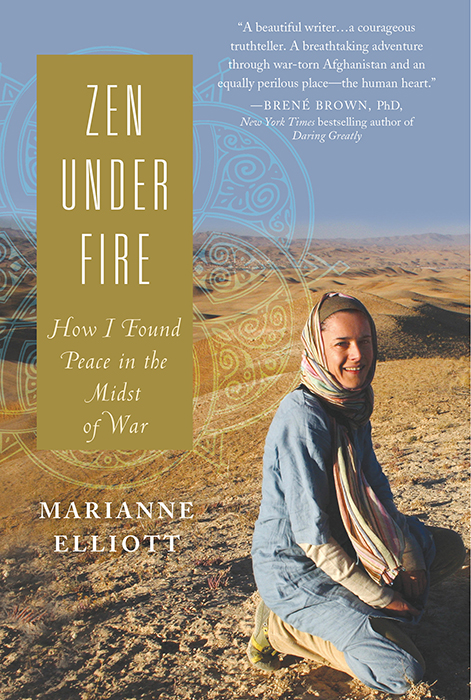

Copyright 2013 by Marianne Elliott

Cover and internal design 2013 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Catherine Casalino

Cover image Vincent Jalabert

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

This book is a memoir. It reflects the authors present recollections of her experiences over a period of years. Some names and characteristics have been changed, some events have been compressed, and some dialogue has been re-created.

Published by Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Originally published in 2012 in New Zealand by Penguin Books, an imprint of the Penguin Group, a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Elliott, Marianne

Zen under fire : how I found peace in the midst of war / Marianne Elliott.

pages cm

Originally published in 2012 in New Zealand by Penguin Books.

Includes bibliographical references.

(pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Elliott, Marianne, 1972- 2. Afghan War, 2001---Personal narratives. 3. Afghanistan--Politics and government--20th century. I. Title.

DS371.413.E44 2013

958.1047092--dc23

[B]

2013010912

Contents

Acknowledgments

To my parents, Ian and Margaret Elliott, who taught me that life can be kind and that we all have a role to play in making it so, and who understood, long before I did, the joy of service. I know they will understand why I also dedicate this book to the people of Afghanistan, especially those who put up with my strange ways and accepted me as a colleague, a neighbor and a friend.

For this book, and for my life in general, I am in the debt of more people than I can thank here. Id like to thank Jake Hardwig, Suraya Pakzad, Fazel Haq Fazel, and Faezeh Mohammedpoor for tolerance and generosity. Gregor Salmon and Kate Khamsi for kindness and encouragement. Alys Titchener, Jolisa and Gemma Gracewood, Rachael King, Mary Parker, Bianca Zander and Helen Heath for reading early drafts and improving them with thoughtful feedback. Susan Piver, Jen Louden, Karen Maezen Miller, and Sharon Salzberg for kind, and wise, words. My agent Laura Nolan for trust, persistence, and great advice. Shana Drehs and everyone at Sourcebooks for confidence, enthusiasm, and a lot of hard work. My family and friends for support, faith, and countless cups of tea and reassurances. And Lucas Putnam, without whom this book may never have been written, for love, immense patience, and Paekakariki.

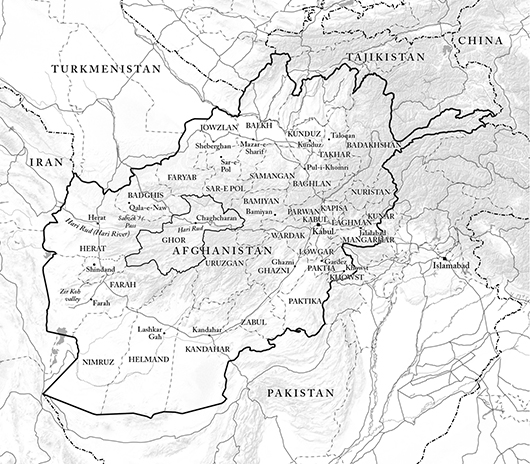

Note on Spelling

There is no standard method of transliterating from Dari into English. Where a Dari place or name is commonly used or reported in English, I have generally chosen the most common usage. Otherwise I have used the simplest spelling of words, place names, and names of people. Ive also included a glossary in the back of the book for readers to reference for terminology used throughout.

Authors Note

When I lived and worked in Afghanistan I had no plans to write about the experience. This book has been written based on my personal journals, detailed notes I kept about my working days, and my memory, a tool known more for its tenacity than its precision. Ive worked hard to be accurate about dates, places and names but given the conditions under which I made the initial notes, some slippage seems inevitable. Despite this, I have done my very best to put down what really happened. As Hemingway said in Death in the Afternoon , aside from knowing what I really felt as opposed to what I think I ought to have felt, putting down what really happened was the hardest part.

The first precept of the yogi and the guiding principle of the humanitarian are the same: do no harm. Any book about a subject as sensitive as human rights in Afghanistan will carry some risk of doing harm. Because of the security situation in Afghanistan, and because even ex-boyfriends have rights, Ive changed the names of anyone (other than public figures) who might suffer from being mentioned here. In the case of my Afghan colleagues and international colleagues still working in Afghanistan, I have sometimes gone further to disguise their identities. Ive known people killed for working with foreigners, and seen a friend flee the country because of death threats based on rumors about her private life. So, to disguise the identities of two characters, I have combined them into one. Another character has been given a new ethnicity and yet another has a new hometown. None of these changes affects the substance of my story, but they allow me to send this book out into the world with less fear of its impact on the lives of the innocent (or even the not entirely innocent).

I slept, and dreamt that life was joy.

I awoke and saw that life was service.

I acted and behold, service was joy.

Rabindranath Tagore

Prologue

Sunday, October 22, 2006: Herat, Afghanistan

Im a month into my new job as a human rights officer for the United Nations Assistance Mission to Afghanistan and Im not yet feeling on top of my game. It is Eid, the holiday that follows the end of the month of Ramadan, and my colleagues are desperate for a break. I am about to be left in charge of the office. Im not sure I am ready for the responsibility, so I double-check with my boss.

Im not backing out on you, I say, but Im having doubts about my ability to do this.

He reassures me. Youll be fine, Marianne. As long as no one kills Amanullah Khan, youll be fine.

His reassurance, I think, is a joke. I have a lot to learn about Afghanistan.

My boss leaves at 9:00 a.m. on Sunday, October 22, 2006. I am now the officer in charge of a United Nations office in the middle of a war zone.

By midday, Amanullah Khan is dead.

1

The Road to Herat

October 2006

I came to Afghanistan almost ten months ago, in the last days of December 2005. Before that, Id been home in New Zealand for five years since my last posting in the Gaza Strip. Having seen the struggle for dignity and justice that characterizes daily life for millions of people around the world, I found it hard to relax completely into my comfortable life in Wellington. Not that Id been wasting my time in New Zealand. I came home from Gaza with three goals: to find a way to work on human rights issues in my own backyard, to get healthy, and to find a boyfriend.

On the first point, my job with the New Zealand Human Rights Commission had been both a challenge and a success. Id taken on a project bigger than many people thought I was ready for, developing a national plan for human rights in New Zealand for the next ten years. Despite inevitable stumbles along the way, I did a decent job of it. The Minister of Justice even thanked me for my steadfast and dynamic approach. On the back of that achievement, Id been appointed to help the government of Timor-Lestethe newest country in the world at the timeto come up with its own long-term human rights strategy.