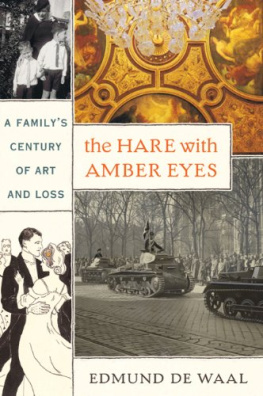

Even when one is no longer attached to things, its still something to have been attached to them; because it was always for reasons which other people didnt graspWell, now that Im a little too weary to live with other people, these old feelings, so personal and individual, that I had in the past, seem to me its the mania of all collectors very precious. I open my heart to myself like a sort of vitrine, and examine one by one all those love affairs of which the world can know nothing. And of this collection to which Im now much more attached than to my others, I say to myself, rather as Mazarin said of his books, but in fact without the least distress, that it will be very tiresome to have to leave it all.

Charles Swann

Marcel Proust, Cities of the Plain

PROLOGUE

In 1991 I was given a two-year scholarship by a Japanese foundation. The idea was to give seven young English people with diverse professional interests engineering, journalism, industry, ceramics a grounding in the Japanese language at an English university, followed by a year in Tokyo. Our fluency would help build a new era of contacts with Japan. We were the first intake on the programme and expectations were high.

Mornings during our second year were spent at a language school in Shibuya, up the hill from the welter of fast-food outlets and discount electrical stores. Tokyo was recovering from the crash after the bubble economy of the 1980s. Commuters stood at the pedestrian crossing, the busiest in the world, to catch sight of the screens showing the Nikkei Stock Index climbing higher and higher. To avoid the worst of the rush hour on the underground, Id leave an hour early and meet another, older scholar an archaeologist and wed have cinnamon buns and coffee on the way in to classes. I had homework, proper homework, for the first time since I was a schoolboy: 150 kanji, Japanese characters, to learn each week; a column of a tabloid newspaper to parse; dozens of conversational phrases to repeat every day. Id never dreaded anything so much. The other, younger scholars would joke in Japanese with the teachers about television they had seen or political scandals. The school was behind green metal gates, and I remember kicking them one morning and thinking what it was to be twenty-eight and kicking a school gate.

Afternoons were my own. Two afternoons a week I was in a ceramics studio, shared with everyone from retired businessmen making tea-bowls to students making avant-garde statements in rough red clay and mesh. You paid your subs and grabbed a bench or wheel and were left to get on with it. It wasnt noisy, but there was a cheerful hum of chat. I started making work in porcelain for the first time, gently pushing the sides of my jars and teapots after Id taken them off the wheel.

I had been making pots since I was a child and had badgered my father to take me to an evening class. My first pot was a thrown bowl that I glazed in opalescent white with a splash of cobalt blue. Most of my schoolboy afternoons were spent in a pottery workshop, and I left school early at seventeen to become apprenticed to an austere man, a devotee of the English potter Bernard Leach. He taught me about respect for the material and about fitness for purpose: I threw hundreds of soup-bowls and honey-pots in grey stoneware clay and swept the floor. I would help make the glazes, careful recalibrations of oriental colours. He had never been to Japan, but had shelves of books on Japanese pots: we would discuss the merits of particular tea-bowls over our mugs of milky mid-morning coffee. Be careful, he would say, of the unwarranted gesture: less is more. We would work in silence or to classical music.

I spent a long summer in the middle of my teenage apprenticeship in Japan visiting equally severe masters in pottery villages across the country: Mashiko, Bizen, Tamba. Each sound of a paper screen closing or of water across stones in the garden of a tea-house was an epiphany, just as each neon Dunkin Donuts store gave me a moue of disquiet. I have documentary evidence of the depth of my devotion in an article I wrote for a magazine when I returned: Japan and the Potters Ethic: Cultivating a reverence for your materials and the marks of age.

After finishing my apprenticeship, and then studying English literature at university, I spent seven years working by myself in silent, ordered studios on the borders of Wales and then in a grim inner city. I was very focused, and so were my pots. And now here I was in Japan again, in a messy studio next to a man chatting away about baseball, making a porcelain jar with pushed-in, gestural sides. I was enjoying myself: something was going right.

Two afternoons a week I was in the archive room of the Nihon Mingeikan, the Japanese Folk Crafts Museum, working on a book about Leach. The museum is a reconstructed farmhouse in a suburb, which houses the collection of Japanese and Korean folk crafts of Yanagi Setsu. Yanagi, a philosopher, art historian and poet, had evolved a theory of why some objects pots, baskets, cloth made by unknown craftsmen were so beautiful. In his view, they expressed unconscious beauty because they had been made in such numbers that the craftsman had been liberated from his ego. He and Leach had been inseparable friends as young men in the early part of the twentieth century in Tokyo, writing animated letters to each other about their passionate reading of Blake and Whitman and Ruskin. They had even started an artists colony in a hamlet a convenient distance outside Tokyo, where Leach made his pots with the help of local boys and Yanagi discoursed on Rodin and beauty to his bohemian friends.