The March into Vienna

On March 13, 1938, the soldiers of the German Reich, in full panoply of war, marched into peaceful Vienna. Through its ancient streets pounded the tread of infantry and the heavy clanking of cannon, tanks and Panzer trucks. The eyes of the young soldiers, beneath their steel helmet brims, stared straight ahead. They turned neither right nor left; neither toward the palaces nor the old baroque churches, nor upward toward the golden spire of St. Stephens Cathedral. Gazing into the distance, the eyes of these marching men were cold, unemotional and earnest, and in their depths lay war.

Aeroplanes cruised over houses, towers and church domes like grey birds of prey. Few Viennese were in the streets. Inside the houses, families were just sitting down to supper. Through closed windows, the unified sound of marching feet and clanging noise penetrated the rooms, chilling the hearts of all who heard with gloom and apprehension. Hours passed before the march of the German soldiers finally ceased, and the drone of aeroplanes persisted far into the night.

In the streets, no rejoicing greeted the victorious army. Vienna, which usually took such great delight in festive celebrations, was silent. There were no smiling strollers to be seen, no lovers embracing in shadowy doorways or sitting on the benches of the parks and promenades. This was no time for love. And from the taverns came no revelers, faces flushed with wine, singing songs of Vienna and its lovely women. The night seemed not only darker, but more oppressive.

In that hour, when a brutal hand grasped the city by the scruff of its neck, there was more involved than war. All European culture was threatened. In Vienna, which found itself transformed overnight into a typical German big town, all the independent spirit, the joy of living, the freedom, the natural intelligence, were harshly forced under the yoke; while a national fanaticism, imported from Germany, murderously stormed through this city which had never been fanatical, but always humane, gay and friendly. What could Vienna mean to the world without its famous joy of living, which had survived so many troublous times, without its culture, nourished from so many different sources, without its sensualityVienna, the Falstaff of German cities, as it was once termed by one of its ironic poets? A legendary city of pleasure, it was quickly being transformed into a prison like those erected throughout Europe in the wake of soldiers in field grey uniforms. What could it mean for the world which loved this city as one loves a beautiful, smiling woman?

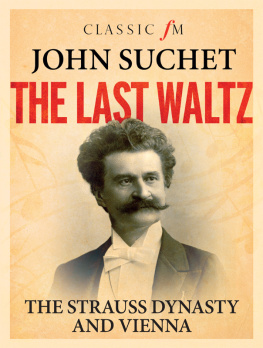

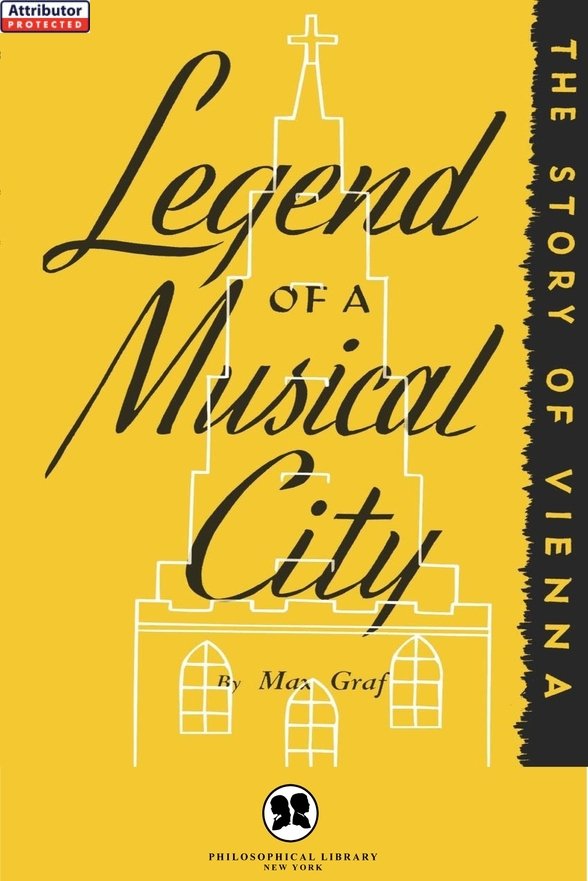

For the world at large, Vienna was, above all, a city of music, or better, the city of music; in fact, the only city in the world which would have been unthinkable without music. One could no more imagine Vienna without it than Rome without St. Peters and the Vatican, Paris without its boulevards, or New York without Wall Street and skyscrapers. Vienna was the city where great composers had lived. It was the city of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert; of Brahms and Bruckner, Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg. From it had emanated the Strauss waltzes which flowed around the world, everywhere preaching the gospel of lifes enjoyment in three-quarter time. From Vienna, too, came the operettas of Lehar, Oscar Strauss and Fall. The city was as full of music as a vineyard with grapes. Not only concert halls and theatres vibrated with sound, but the air itself. As Paris was the city of the mind, Rome the center of the Catholic world, London the capital of the greatest empire of modern times, so was Vienna the acknowledged music capital of the world. Musicians from all corners of the globe came there to study. Virtuosi came, too, because success in Vienna was a prerequisite of being world-famous. The Vienna State Opera, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, the Vienna Conservatory were internationally recognized. Every tourist visited the houses where the great classics had lived just as, in Rome, he would visit St. Peters and Michael Angelos statue of Moses. Every musician who came to Vienna visited the graves of the classic musicians in the same spirit as a pious Catholic makes a pilgrimage to the tombs of the saints in Rome. Everything of greatness and of value which had been accomplished in Viennathe famous medical school, the Art Academy, the new living quarters for workerswas dwarfed beside its place in music.

In the course of centuries, Vienna had become a kind of fairy-tale city. And, as in all fairy-tales, life there was easier, more brilliant and more exciting than anywhere else. Everywhere there was song and sound. The fairy-tale omits to say, of course, that there, as in all modern metropolises, poverty and misery stalked through the streets, in its outskirts, and that, despite the fabled gaiety, hard and earnest work was done. The tale does not speak of the political battles which took place there, nor of the colossal rise of the workingman to political rights, to education, culture, and finally, to political might. According to the saga of Vienna, there was only loving, dancing, singing, drinking and music-making. This legend has been propagated primarily by the motion picture which, for the masses of our time, is the biggest story-teller of them all. Everyone has seen films whose scenes were laid in Vienna. In such pictures, certain connoisseurs of mass taste depicted the fairy-tale Vienna. There were always poor but decent girls who fell in love with dashing officers, nobles and grand dukes. Lovers sat in Prater inns under chestnut trees, and everywhere there was music. Orchestras played waltzes, peasants sang Viennese songs. There were kisses and embraces during the music. Although this type of Viennese film belongs to the most mendacious products of fabrication, it is none the less characteristic that in every case Vienna and music are inseparable.

On that sad March day which was the beginning of a great world catastrophe, the city of music was struck dumb. As in Haydns Farewell Symphony, the musicians packed up their music and their instruments, and the candles burned down in the music stands. A great epoch of music came to an end on this day.

Ten generations had labored at the development of Vienna into a great music capital. The long process had begun at the end of the 17th century, when Vienna had achieved the rank of a European city noted for music. From that time on, the graph of its development rose higher and higher in an unbroken ascent. Its peak was reached at the time when the classic musicians lived in Vienna, and on this marvelous construction, the powerful towers of the Haydn symphony, the Mozart Opera, the Beethoven Music of Humanity, and the Schubert song stood in all their glory. Then the graph descends to points which are, nevertheless, still high and strongBrahms and Bruckner. Finally came the great demolisher of the architecture of classic music, Arnold Schoenberg. There ended a unique and great development such as the world had seen only twice before: first, when Greek art rose to the brilliance of the Periclean Age, to Phidias, to the tragic poets, to Plato, Aristotle, to the divine laughter of Aristophanes, and to the mighty marble pillars which looked down from the Acropolis to the blue sea. And a second time, when the painting of the Renaissance had risen to Raphael, Michael Angelo and Titian. Viennas development was a similar one, showing a steady growth of artistic fantasy, an increasingly large creative scope, the work of generations, a continuously richer unfolding of the powers of intellect. It was like a symphony, which flowed on to more and more powerful crescendos, to magnificent climaxes, and then, in 1938, died away with a dreary and mournful sound.