T HE H ARVARD C OMMON P RESS

535 Albany Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02118

2001 by Judith M. Fertig

Illustrations 2001 by John MacDonald

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by

any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage

or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fertig, Judith M.

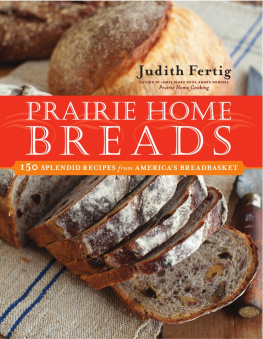

Prairie home breads : 150 splendid recipes from America's breadbasket / Judith M. Fertig ;

illustrations by John MacDonald.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 1-55832-172-1 (hc : alk. paper)

1. Cookery (Bread) I. Title.

TX769.F477 2001

641.8'15dc21 00-057510

Special bulk-order discounts are available on this and other Harvard Common Press books. Companies

and organizations may purchase books for premiums or resale, or may arrange a custom edition, by

contacting the Marketing Director at the address above.

Cover illustration by John MacDonald

Cover and interior design by Kathy Herlihy-Paoli, Inkstone Design

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my family,

the latest in a long line of bread bakers

Acknowledgments

First of all, I wish to thank everyone who generously gave of their time and talents to help create this book, including my agent and friend Karen Adler, editors Dan Rosenberg and Judith Sutton, and everyone at The Harvard Common Press.

Thanks also to my mother and father, Jean and Jack Merkle, for researching our own family's bread-baking past and introducing me to schnecken on a visit to Cincinnati. My children, Sarah and Nick Fertig, for bravely suffering through an ongoing blizzard of flour and bowls of starter gurgling all over the house. My former sister-in-law Bev Fertig for making family gatherings so delicious with her homemade bread and rolls. All the great bakers I have met, and all the people who have helped me with wheat and bread stories for newspapers and national magazines, including: Lisa Grossman, Alvin Brensing, Jane Pigue, Susan Welling, Donna Grosko, Ted and Helen Walters, Don Coldsmith, everyone at Wheat-Fields Bakery, Jean Keneipp, Janice Cole, Colman Andrews and Christopher Hirsheimer, Linda Hodges, Bonnie Knauss, Debbie Givhan-Pointer, Gerry Kimmel-Carr, Bill Penzey, the Wenger family, Herb and Susan White, Emogene Harp, and Judy Pilewski.

When you want to make sure that every bread recipe is clear, concise, and ultimately successful, you need the help of a lot of people. My sincere thanks to Mary Pfeifer, Kim Fosbre, and the test kitchens of Cooking Pleasures and Saveur magazines for helping me test recipes formally. And to Dee Barwick, Karen Adler, Jean Merkle, and Julie Fox for helping me test recipes informally.

Introduction

I live and work in a part of the country that takes the phrase "daily bread" very seriously. Although I live in a suburb of Kansas City, wheat fields are only five minutes from my house. We are witness to the cycle of wheat, as much a part of our daily commute as the traffic report on the radio.

As we drive by the wheat fields in the fall, we see the seeds being drilled into the ground. (Winter wheat seeds are planted deep to survive the cold and stay moist.) By early November, the emerald-green wheat grass has sprouted after a chilly rainfall. During January and February, the dormant wheat grass stays green when every other grass has turned brown and sere. As the weather warms up in April, we know spring is here when the wheat starts to grow again. By early June, we're blessed to see a knee-high field of chartreuse-green wheat rustling in the breeze against a brilliant blue skyone of my favorite sights. By late June, the wheat fields have turned golden, bordered with purple wildflowers and native sunflowers that are starting to reach toward the sky. Under the brilliant sunlight, I have to remind myself that this is Kansas, not the South of France. By early July, the harvest is complete, and the fields lie fallow.

That's when the business side of "daily bread" takes over. In rural communities, the journey from wheat field to grain elevator and flour mill is often a matter of minutes for the family farmers whose lives revolve around wheat, and whose dinner tables revolve around homemade bread.

In Kansas City, the wheat-growing cycle has become an integral part of other cycles. The milling and baking industry estimates that it takes approximately twelve people, from beginning to end, to produce one ten-pound bag of flour. Besides the farmer, production involves the trader, the writer, the grain elevator employees, the miller, and the grocerbefore you scoop out the flour to make bread.

At the Kansas City Board of Trade, traders speculate on the quantity and quality of the grain harvest as wheat futures are bought and sold daily. The leading baking industry journal, Milling and Baking News, is headquartered nearby, where Sosland Publishing Company writers and editors can keep their fingers on the pulse of the business. Towering grain elevators, like prairie cathedrals, anchor the landscape along Southwest Boulevard and where the Missouri River flows under the concrete tangle of highways.

After storage, the wheat berries are milled into flour at mills owned by Archer Daniels Midland, General Mills, ConAgra, and Cereal Food Processors. Other local companies make vital wheat gluten from the kernels. The flour makes its way onto grocery store shelves or to huge commercial enterprises like Interstate Bakeries. And every day in Kansas City, traditional, ethnic, and artisanal bakeries turn out countless loaves of bread, feeding us with a true taste of home.

Symbolic of hearth and home, stability, and freedom from want, a good loaf of bread still speaks to us even in an age of relative affluence. The indescribable aroma of bread baking in the oven says "home" like nothing else. Its aroma triggers that primitive part of our brains that tells us that all is well. We're settled, safe, and secureeven when it's harder than ever to keep up with the ever-quickening pace of change. We know that we're never really settled anymore. But when we enjoy the sensual pleasure of bread warm from the oven, we feel settled. That's the power of good bread.

) on a Saturday morning turns a simple get-together into a memorable event. We all understand the language of bread.

In the course of developing and testing the recipes in this book, I also came to understand how flour, bread, and baking became essential ingredients in my family's recipe for happiness and well-being. During the late nineteenth century, my great-grandfather George Willenborg left northwestern Germany to settle in Cincinnati, Ohio. As a flour salesman, he called on a small grocery store and met a pretty young girl who did the meat cutting. Gertrude Rotherm was also a German immigrant, who had come from the same area as George. The two struck up a conversation each time he called on the store. After many more visits than flour sales actually warranted, the two-time widower and the feisty meat cutter were married. She raised his children by his two former wives, and they had three children of their own. George passed away when his daughter Gertrude, my grandmother, was a teenager.

Next page