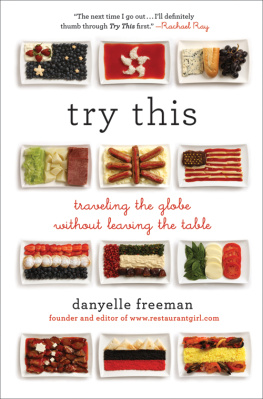

T RY T HIS

TRAVELING THE GLOBE

WITHOUT LEAVING THE TABLE

danyelle freeman

For my mom and dad,

who taught me that the two most

important things in life

are family and food.

Im eternally grateful for your limitless love

and your encouragement to dream.

You will live in my heart always.

And for Amanda and Heath,

who fill my every day with love and laughter.

Everyone should be lucky enough

to have a sister and a brother like you.

Thank you for your support and, most importantly,

for always sharing your food with me.

(As if you had a choice.)

I am not a glutton.

I am an explorer of food.

E RMA B OMBECK

Contents

S ome people read romance novels in their free time. Others prefer thrillers or fashion magazines. Some spend their commutes flipping through gossip columns, while others scrutinize the business section. Me, I read menus. And in New York, menus are everywhere you look. Theyre prominently posted in restaurant windows or handed out by sidewalk hawkers at busy corners. Instead of avoiding eye contact or moving to the other side of the sidewalk, Im the girl who asks for one, even when Im not solicited. Ill spot a menu guy as Im darting down the street, late for an important meeting, and beeline over for one of my own. Reading menus soothes me.

It doesnt have to be anything fancy. Hell, if I pass a burger joint, Ill check out the flimsy paper menu. Some chefs make their own ketchup or pickle their own pickles; some serve homemade potato chips or sweet potato fries instead of skinny potato fries; some bake their buns in-house or melt cheddar or blue cheese over their patties instead of the same old American cheese.

And burgers are just one juicy possibility: theres a universe of food and chefs with different opinions on what delicious tastes like. Some think delicious tastes like pillows of freshly made ricotta ravioli bathed in a sweet, tangy tomato sauce or barely seared scallops in lemongrass-laced coconut milk sauce; some a corn tamale studded with moist shreds of pork; others delicate, nearly translucent soup dumplings filled with minced crab, pork, and a rich broth. The possibilities are endless.

Long before I imagined a career in food, I made it my job to visit every respectable restaurant in my Zagat guide. Instead of a bubble bath or late-night TV before bed, Id pull out my highlighter and mark up my little maroon book. When I graduated from college, I moved to Manhattan to conduct my food-obsessed fieldwork while experimenting with careers in psychology, acting, sitcom writing, jewelry design, and film development. Before then, I had never slurped noodles at a ramen counter or tasted a French bouillabaisse. Id never gone out for Indian curry or do-it-yourself Korean barbecue. I had a lot of eating to do. Culinary matters quickly became all-consuming. I skipped auditions to linger over dim sum in Chinatown and took extra-long lunch breaks from my film job to try the new Vietnamese spot on the other side of town. Sometimes Id eat two full meals in one night or one meal at two different restaurants on the same night. Every spare dollar went to investigating a new restaurant and sampling as many dishes as I possibly could. After dinner, Id crawl under the covers, pick up my maroon book, and cross another conquest off my to-do list, scribbling my own review in the margin.

I read every review in every magazine and newspaper I could get my hands on. Id make Sunday night foodie calls to set up the coming weeks dinner dates. I began inventing excuses to avoid dining out with friends who proved themselves unadventurous at the dinner table. I judged my dates by what restaurants they chose, what they ordered, and how they ate it. I eliminated potential mates on the basis of dietary restrictions. I was on a mission to try anything and everything. Restaurants were my drug of choice. I couldnt get enough. Most twenty-two-year-old girls longed for Jimmy Choos and piles of Prada. I dreamed of dinner at New Yorks Le Cirque and Monacos Le Louis XV. It was exhausting. It was exhilarating. I started blogging about my meals, just so I could maintain my serious restaurant habit. I was addicted to restaurants, so I thought it only fitting to call myself Restaurant Girl.

This kind of obsession runs in families. When I was a child, my parents braved gang wars for good food. Literally. On Sunday evenings, we would drive from Short Hills, the quiet, suburban town in New Jersey where I grew up, to the then gang-riddled Elizabeth, New Jersey. My parents locked the car doors and made me, my brother, and my sister hunch beneath the windows to avoid potential gunfireall in the name of veal cutlet, ravioli, and mushroom pizza at Spiritos. Ive now eaten in many four-star restaurants, and that dingy joint still serves the best garlic salad, veal, ricotta ravioli, and fountain soda Ive ever had. My parents have passed away, but my brother, sister, and I dutifully return to Spiritos a few times a year, just to make sure we arent romanticizing those garlic-filled Sundays with our parents.

Spiritos opened over sixty years ago, and its still going strongand still cash only. They dont take reservations, they use an old manual register to make change, and the checks are all handwritten by waitresses with beehive hairdos and pencils tucked behind their ears. They refuse to write down your order and yet, somehow, never get it wrong. If you ever end up on a flight that connects at Newark Airport, youd be wise to take a later plane. Most local taxi drivers should know Spiritos by name, so ask one to take you and see for yourself. (And bring me back a ravioli, please.)

Both my parents were foodies before the word even existed. On weekends our family motto might as well have been: Will travel for food. Our family field trips to New York werent so much about seeing the Statue of Liberty or the Christmas tree at Rockefeller Center as they were about paper-bagged chestnuts and street cart pretzels spackled with salt. That was before dinner. Then wed head down to Little Italy for unspeakable amounts of pasta, shrimp scampi, baked clams, and veal scaloppini. Our final stop was always Ferraras, just down the street, for biscotti, torrone, and chocolate gelati. Summers at the shore meant saltwater taffy, vinegar-doused French fries, and caramel apples. Wed settle into a slippery plastic booth at some fish shack and, wearing plastic bibs and wielding claw crackers and wet naps, feast on steamers, fried clam strips, and lobster rolls. If we came on the right night, wed find sauted soft-shell crabs on the menu. My mom made soft-shell crabs any chance she could. She wasnt the best cookmore concerned with eating than cookingbut her sauted soft-shell crabs were better than any Ive had in a restaurant or picked up fresh from the store. (Im still on the hunt for a better rendition.)

Both my parents grew up in poor families, but that didnt stop either of them from eating well. If all they could afford was bread and cheese, they ate the freshest bread and freshly sliced (never packaged) cheese. We didnt eat at the kind of restaurants that required reservations, but we ate splendidly.

When my mom didnt feel like cooking, we went to local diners and reviewed their workmanship in the kitchen. We grimaced at diners that served canned strawberries with their waffles or skimped on the chocolate chips in our pancakes and gave bonus points to diners that used semisweet chocolate chips instead of milk chocolate. On school nights we mostly stuck to local spots, where we got our fix of saffron-stained seafood paella and garlic shrimp from our favorite Spanish restaurant, or Italian classicseggplant rollatini, mozzarella in carrozza, shrimp francese, escarole and beans, and gnocchi in tomato saucefrom our favorite Italian restaurant.

Next page

![Freeman - Pro design patterns in Swift: [learn how to apply classic design patterns to iOS app development using Swift]](/uploads/posts/book/201359/thumbs/freeman-pro-design-patterns-in-swift-learn-how.jpg)