Thank you for buying this ebook, published by HachetteDigital.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and news about ourlatest ebooks and apps, sign up for our newsletters.

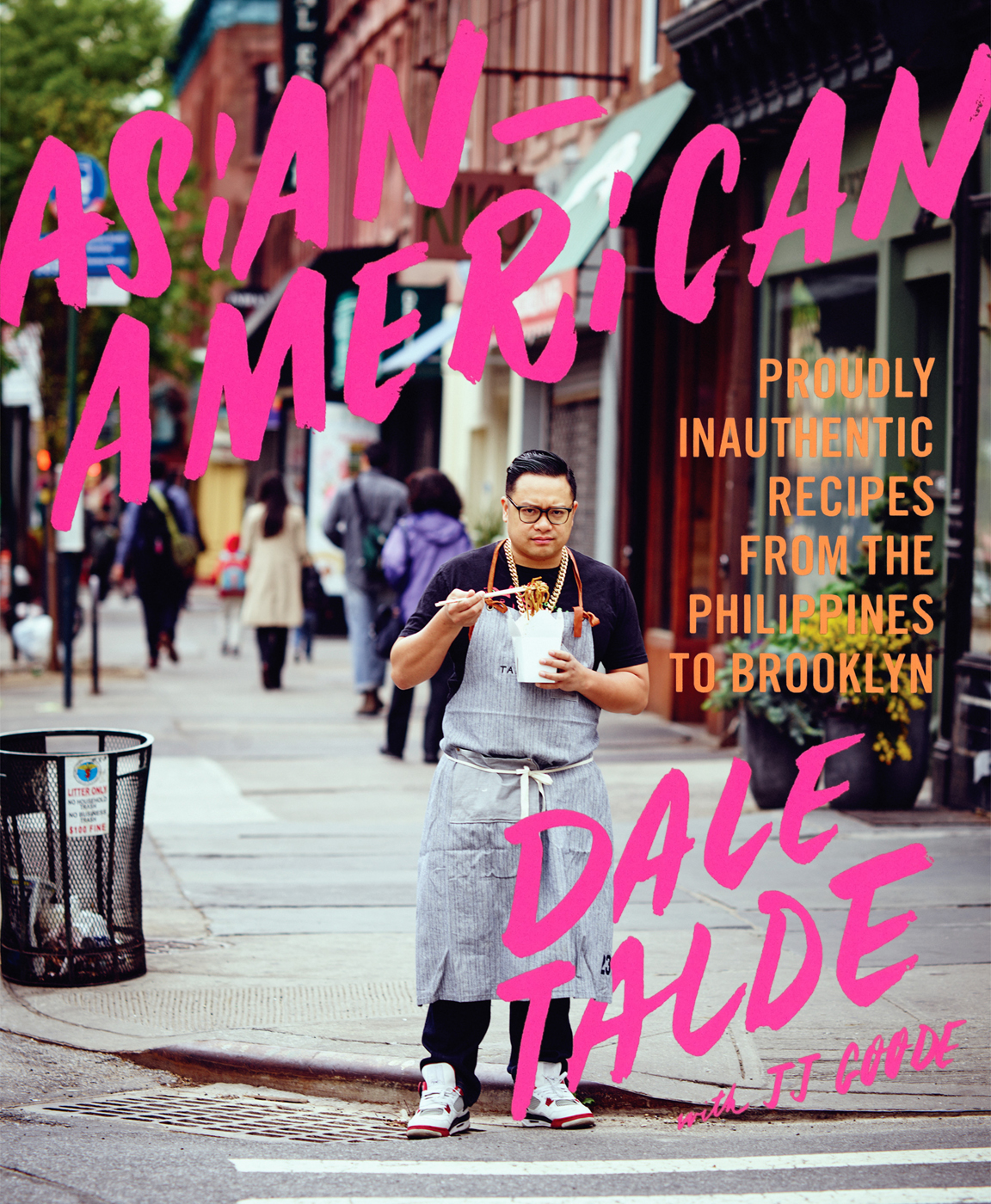

Copyright 2015 by Dale Talde, LLC

Photos of family and friends appear courtesy of the Talde family and are from Dale Taldes personal collection. All other photos are by William Hereford.

Cover copyright 2015 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Cover design by Elizabeth Connor

Hand lettering by Joel Holland

Cover photographs William Hereford

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Grand Central Life & Style

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

GrandCentralLifeandStyle.com

twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First ebook edition: September 2015

Grand Central Life & Style is an imprint of Grand Central Publishing.

The Grand Central Life & Style name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4555-8525-0

E3

To my familymy father, Salvador; my mother, Eva; my brother, Ian; and my sister, Aileen

T heres a pigs head in the oven again. Im just a kid, no more than six years old, but Im not surprised when I peer over my aunts shoulder as she opens the oven and I see the pigs sleepy eyes staring back at me. At my aunts house, there was often a pigs head in the oven. Im not talking about on special occasions. Im talking about on some random Thursdayeven when she had no reason to think we were coming over. The pigs head was the Filipino equivalent of cheese and crackers. It was just-in-case-theres-company food.

My mom preferred fish heads to pig. She was always hitting the supermarket to ask the fish guy whether he had any lying around that hed be willing to part with at no charge. He typically did, because none of his other customers wanted them. Way before nose-to-tail cooking was a chefs badge of honor, Filipino moms were eating off-cuts for the thrift of it.

After my moms 16-hour shift at the Chicago hospital where she worked as a nurse, she got to come home to cook dinnerlucky herfor my dad, my brother and sister, and my bratty ass. She cooked Filipino food almost exclusivelyor at least an immigrants approximation. It was called Fil-Am food (short for Filipino-American) and was as Filipino as you could get without having access to half of the proper ingredients. When we made fried rice, we made do without the Filipino sausage called longaniza and used Spam instead. At some point, Mom got fed up with the lack of Asian vegetables around town and started trafficking, sneaking seeds back into the U.S. in her purse when she returned from trips to the Motherland and planting them in the garden. That way, we could have bitter melon and water spinach. Mom was thrilled that she could get canned sardines, though. It might have been her favorite ingredient. She would cook soffrito, the Spanish and Italian flavor base made from slowly sizzled vegetables, the Filipino waytomato, garlic, and onions cooked down until the onions were almost burnt but in a good wayand dump in cans of sardines in tomato sauce. Shed mash it all up and use the result as a sort of sauce for rice or eggs.

Heads were just one of the many things that ended up on our table, which seemed to be always filled with food. It became a joke among the Filipino families we rolled with: Whenever anyone came to our place, whenever we visited Filipino friends, even if wed just gotten back from dinner, someones mom, aunt, or cousin would ask, So, whos hungry? Just in case we were, a table of food was usually waiting. More often than not, the spread was pork-heavy. Sausage, chops, stew, head. Sometimes the pork was served with more porkFilipinos are fucked-up like thatsuch as crunchy pork rinds for sprinkling or Mang Tomas, a sort of gravy made with sugar, vinegar, bread crumbs, and pork liver.

Sometimes Mom would make dinuguan, a nasty-looking, deep-brown slop from the region of the Philippines my parents come from. The first few times she made it for us, she tried to get us kids to eat it by calling the stew by its nickname: chocolate meat. That was a well-worn trick used by Filipino parents to make dinuguan seem like something a kid might want to eat. A couple of disappointing bites and we were on to her. There was no chocolate in there. The color came from cooked blood. And this stuff was organ-ed outthere was liver, heart, and lung, not to mention ear and snout. Even though we eventually came to like the stuff, we developed a rule of thumb for dinuguan: Only eat it if you know the person who made it. Otherwise, youre taking your life in your hands.

And there was always rice. Always. Even when Mom occasionally gave in and made non-Filipino food for dinner. One time she made spaghetti for dinner and my dad absolutely killed his bowl, which I swear was like one of those family-style portions youd get at Olive Garden. Then he asks Mom, Wheres the rice? Thats commitment right there. He ended up launching right into meal number two: a bowl of rice and canned sardines with chile-spiked vinegar on the side. There was always something on the side, no matter what we ate: tiny fried dried fish, shrimp paste mixed with vinegar, or bowls of fresh bird chiles as long as my thumbnail, which wed eat whenever we craved pain.

For years, this all seemed normal to mepig heads in the oven, fish heads in the pot, rice in bowls, and a shrimp-paste smell in the air.