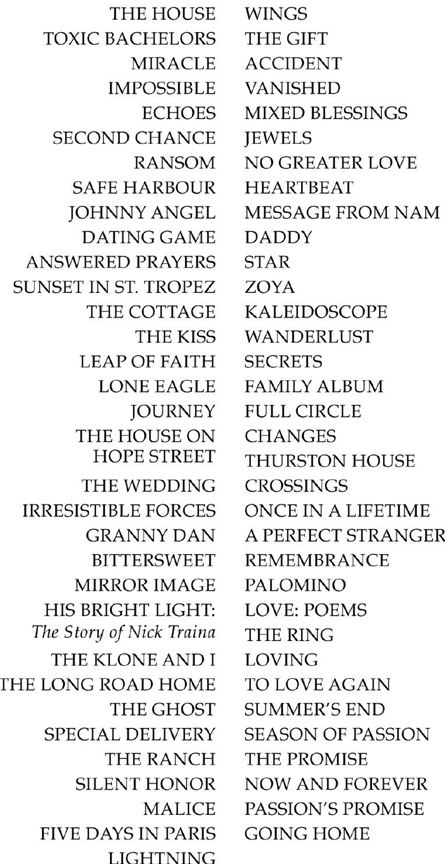

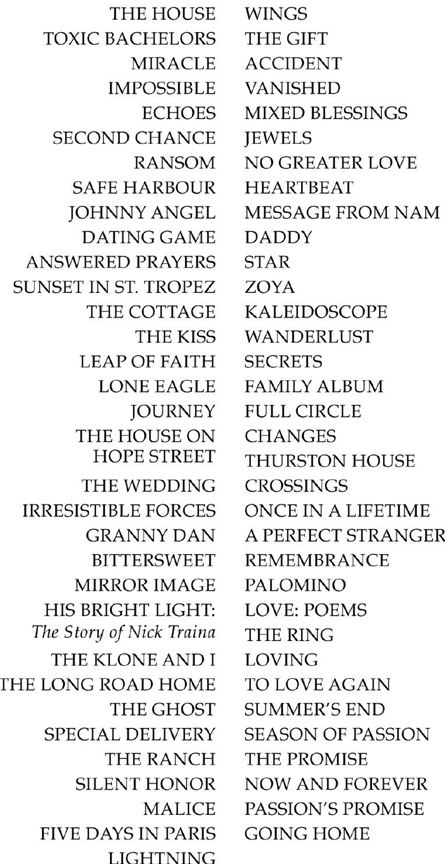

Also by Danielle Steel

Chapter 1

It was almost impossible to get to Lexington and Sixty-third Street. The wind was howling, and the snow drifts had devoured all but the largest cars. The buses had given up somewhere around Twenty-third Street, where they sat huddled like frozen dinosaurs, as one left the flock only very rarely to venture uptown, lumbering down the paths the snowplows left, to pick up a few brave travelers who would rush from doorways frantically waving their arms, sliding wildly to the curb, hurling themselves over the packed snowbanks, to mount the buses with damp eyes and red faces, and in Bernie's case, icicles on his beard.

It had been absolutely impossible to get a taxi. He had given up after fifteen minutes of waiting and started walking south from Seventy-ninth Street. He often walked to work. It was only eighteen blocks from door to door. But today as he walked from Madison to Park and then turned right on Lexington Avenue, he realized that the biting wind was brutal, and he had only gone four more blocks when he gave up. A friendly doorman allowed him to wait in the lobby, as only a few determined souls waited for a bus that had taken hours to come north on Madison Avenue, turned around, and was now heading south on Lexington to carry them to work. The other, more sensible souls had given up when they caught their first glimpse of the blizzard that morning, and had decided not to go to work at all. Bernie was sure the store would be half empty. But he wasn't the type to sit at home twiddling his thumbs or watching the soaps.

And it wasn't that he went to work because he was so compulsive. The truth was that Bernie went to work six days a week, and often when he didn't have to, like today, because he loved the store. He ate, slept, dreamed, and breathed everything that happened from the first to eighth floor of Wolffs. And this year was particularly important. They were introducing seven new lines, four of them by major European designers, and the whole look of American fashion was going to change in men's and women's ready-to-wear markets. He thought about it as he stared into the snowdrifts they passed as they lumbered downtown, but he was no longer seeing the snow, or the stumbling people lurching toward the bus, or even what they wore. In his mind's eye he was seeing the new spring collections just as he had seen them in November, in Paris, Rome, Milan, with gorgeous women wearing the clothes, rolling down the runway like exquisite dolls, showing them to perfection, and suddenly he was glad he had come to work today. He wanted another look at the models they were using the following week for their big fashion show. Having selected and approved the clothing, he wanted to make sure the models chosen were right too. Bernard Fine liked to keep a hand in everything, from department figures to the buying of the clothes, even to the selection of the models, and the design of the invitations that went out to their most exclusive customers. It was all part of the package to him. Everything mattered. It was no different from U.S. Steel as far as he was concerned, or Kodak. They were dealing in a product, in fact a number of them. And the impression that product made rested in his hands.

The crazy thing was that if someone had told him fifteen years before when he was playing football at the University of Michigan that he would be worried about what kind of underwear the models had on, and if the evening gowns would show well, he would have laughed at them or maybe even have busted their jaw. Actually, it struck him funny now, and sometimes he sat in his huge office on the eighth floor, smiling to himself, remembering back then. He had been an all-around jock when he was at Michigan, for the first two years anyway, and after that he had found his niche in Russian literature. Dostoevski had been his hero for the first half of junior year, matched only by Tolstoi, followed almost immediately by Sheila Borden, of slightly less stellar fame. He had met her in Russian I, having decided that he couldn't do the Russian classics justice if he had to read them in translation, so he took a crash course at Berlitz, which taught him to ask for the post office and the rest rooms and find the train in an accent which impressed his teacher enormously. But Russian I had warmed his soul. And so had Sheila Borden. She had sat in the front row, with long straight black hair hanging to her waist romantically, or so he thought, her body very lithe and tight. What had brought her to the Russian class was her fascination with ballet. She had been dancing since she was five, she had explained to him the first time they talked, and you don't understand ballet until you understand the Russians. She had been nervous and intense and wide-eyed, and her body was a poem of symmetry and grace which held him spellbound when he went to watch her dance the next day.

She had been born in Hartford, Connecticut, and her father worked for a bank, which seemed much too plebeian to her. She longed for a history that included greater poignancy, a mother in a wheelchair a father with TB who would have died shortly after she was born. Bernie would have laughed at her the year before, but not in his junior year. At twenty he took her very, very seriously, and she was a fabulous dancer, he explained to his mother when he went home for the holidays.

Is she Jewish? his mother asked when she heard her name. Sheila always sounded Irish to her, and Borden was truly frightening. But it could have been Boardman once, or Berkowitz or a lot of other things, which made them cowardly, but at least acceptable. Bernie had been desperately annoyed at her for asking him the question she had plagued him with for most of his life, even before he cared about girls. His mother asked him that about everyone. Is he Jewish is she what was his mother's maiden name? was he bar mitzvahed last year? what did you say his father did? She is Jewish, isn't she? Wasn't everyone? Everyone the Fines knew anyway. His parents wanted him to go to Columbia, or even New York University. He could commute, they said. In fact, his mother tried to insist on it. But he had only been accepted at the University of Michigan, which made the decision easy for him. He was saved! And off to Freedomland he went, to date hundreds of blond blue-eyed girls who had never heard of gefilte fish or kreplach or knishes, and had no idea when Passover was. It was a blissful change for him, and by then he had dated all the girls in Scarsdale that his mother was crazy about and he was tired of them. He wanted something new, different, and a trifle forbidden perhaps. And Sheila was all of those. Besides she was so incredibly beautiful with huge black eyes, and shafts of ebony hair. She introduced him to Russian authors he had never heard of before, and they read them allin translation of course. He tried to discuss the books with his parents over the holidays, to no avail.

Your grandmother was Russian. You wanted to learn Russian, you could have learned Russian from her. That wasn't the same thing. Besides, she spoke Yiddish all the time His voice had trailed off. He hated arguing with them. His mother loved to argue about everything. It was the mainstay of her life, her greatest joy, her favorite sport. She argued with everyone, and especially with him.

Don't speak with disrespect about the dead!

I wasn't speaking with disrespect. I said that Grandma spoke Yiddish all the time

She spoke beautiful Russian too. And what good is that going to do you now? You should be taking science classes, that's what men need in this country today economics She wanted him to be a doctor like his father, or a lawyer at the very least. His father was a throat surgeon and considered one of the most important men in his field. But it had never appealed to Bernie to follow in his father's footsteps, even as a child. He admired him a great deal. But he would have hated being a doctor. He wanted to do other things, in spite of his mother's dreams.