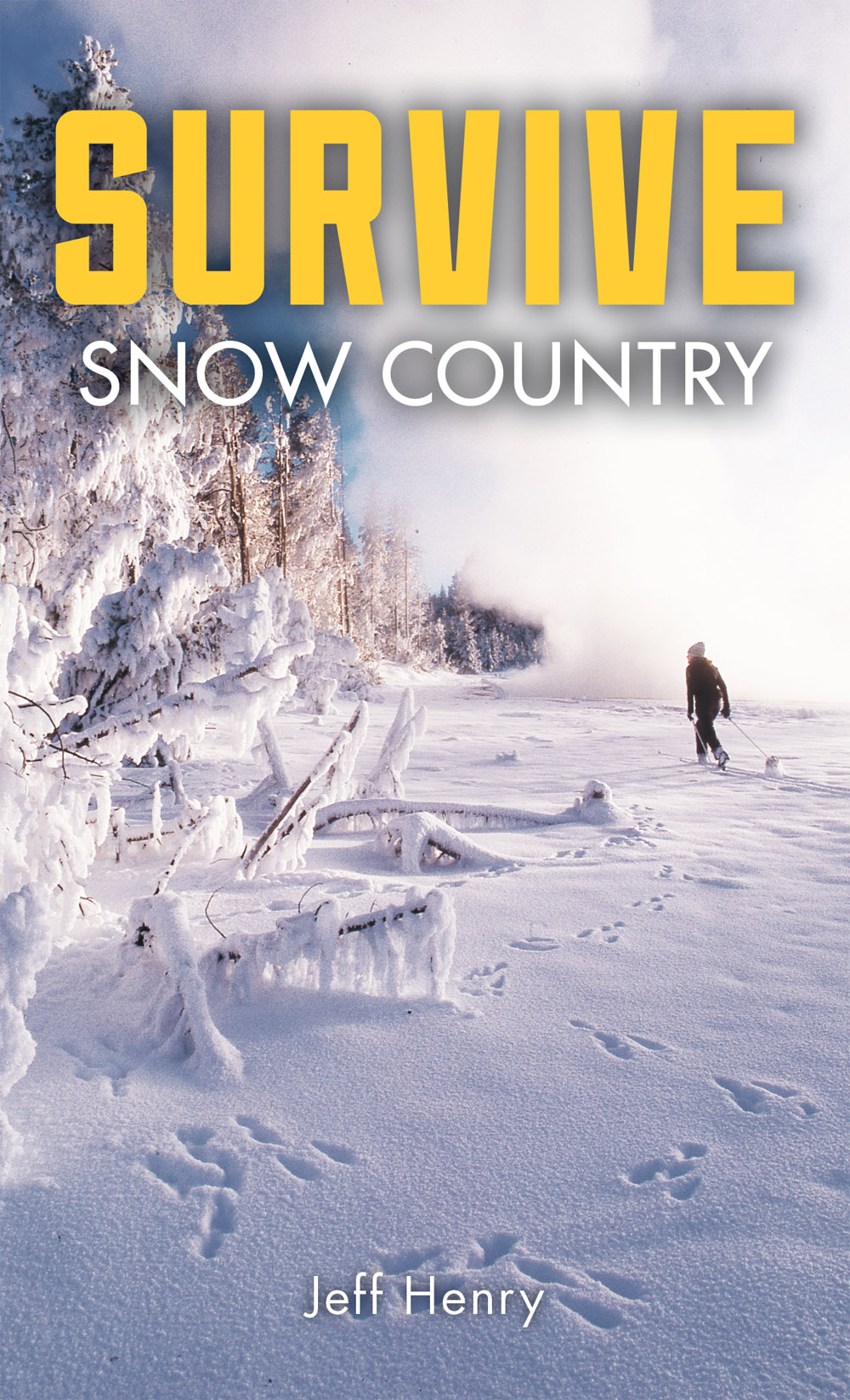

SURVIVE

SNOW COUNTRY

To my dad, Jack Henry, and to all the others who have suffered from Alzheimers disease.

FALCON

An imprint of Globe Pequot

Falcon and FalconGuides are registered trademarks and Make

Adventure Your Story is a trademark of Rowman & Littlefield.

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2017 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

Photos by Jeff Henry unless otherwise credited

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data available

ISBN 978-1-4930-2385-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-4930-2386-8 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The author and Rowman & Littlefield assume no liability for accidents happening to, or injuries sustained by, readers who engage in the activities described in this book.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Several people provided advice, information, or anecdotes for this book. For such contributions I would like to thank Jason Fatourous, Ron Wilkes, Shane Roos, Michael Keator, Rebekah Houck, Crystal Cassidy, Virgia Bryan, Jenny Wolfe, Scott Hamilton, Louise Mercier, and Joe Bueter.

I also would like to thank the following people for their contributions of photographs or other illustrations: Larry Lahren of Anthro Research in Livingston, Montana; Jerry Brekke, historical consultant in Livingston, Montana; Eric Knoff of the Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center in Bozeman, Montana; Peter Lewis of the Stonehearth Open Learning Opportunities (SOLO) School in Conway, New Hampshire; Mariah Gale Henry for compiling the wind-chill chart; Lisa Culpepper of Culpepper Photography in Gardiner, Montana; and Jim Halfpenny of A Naturalists World in Gardiner, Montana.

INTRODUCTION

If you have picked up this book and are reading these words, youre probably like me in the sense that you enjoy winter and snow and the sports that go with them. Indeed, its hard for me to fathom that there is anyone who doesnt like snow and cold weather.

Winter scenes are breathtakingly beautiful, and there is such a sense of wonder and romance in the snow itself. As for winter sports, who could not like touring through winter wonderlands in a car or on a snowmobile, to say nothing of lovely snowshoe treks through winter-whitened woods, or schussing downhill on skis? For me, and for many of my friends, activities like those are about as good as it gets.

But, of course, there is a flip side to wintry weather and snowy environments. Weather can change quickly. Snowmobiles can break down and cars can get stuck in the snow, while snowshoers and cross-country skiers can wind up lost or injured in the backcountry.

The purpose of this book is to help you avoid winter-related problems in the first place. Second, the book contains information that hopefully will help you deal with survival problems that can and often do occur in wintry situations.

To write the book, I have drawn on a lifetime of working and playing in the snow. As much as possible I have arranged my life to spend a maximum amount of time outdoors in the winter, working jobs like wildlife researcher, park ranger, freelance photographer specializing in winter subjects, and more. My favorite avocation for almost forty years has been sawing snow from tourist buildings in Yellowstone National Park to prevent them from collapsing under winters weight. While I have spent most of my time in the wintry outdoors alone, I have never suffered a significant injury or otherwise fallen into any sort of serious predicament. As an old-timer I once knew used to say, the difference between livin and dyin is knowin, and hopefully this book will help you learn some of what is necessary to get by in the snowy world of winter.

HIKING IN SNOW COUNTRY

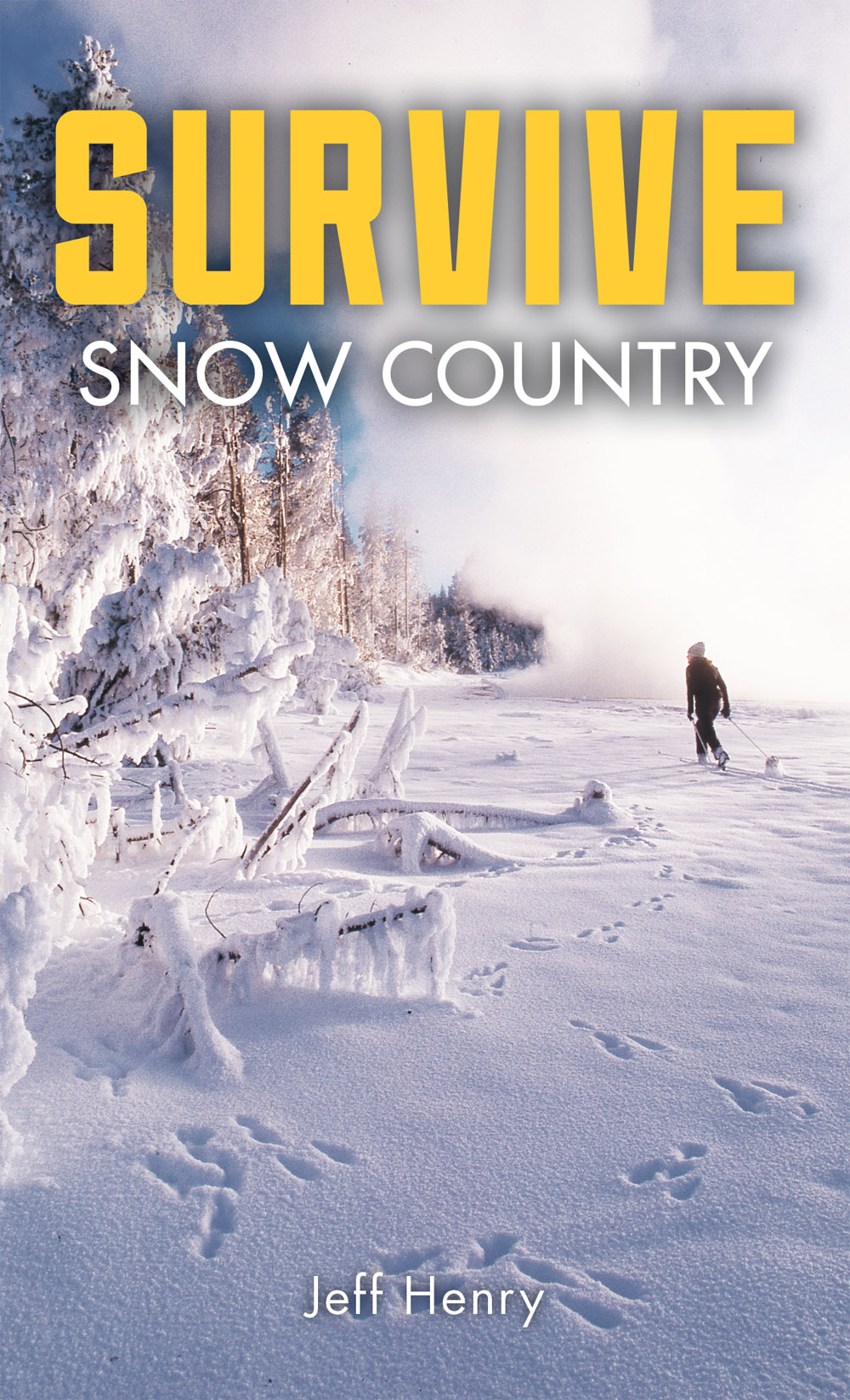

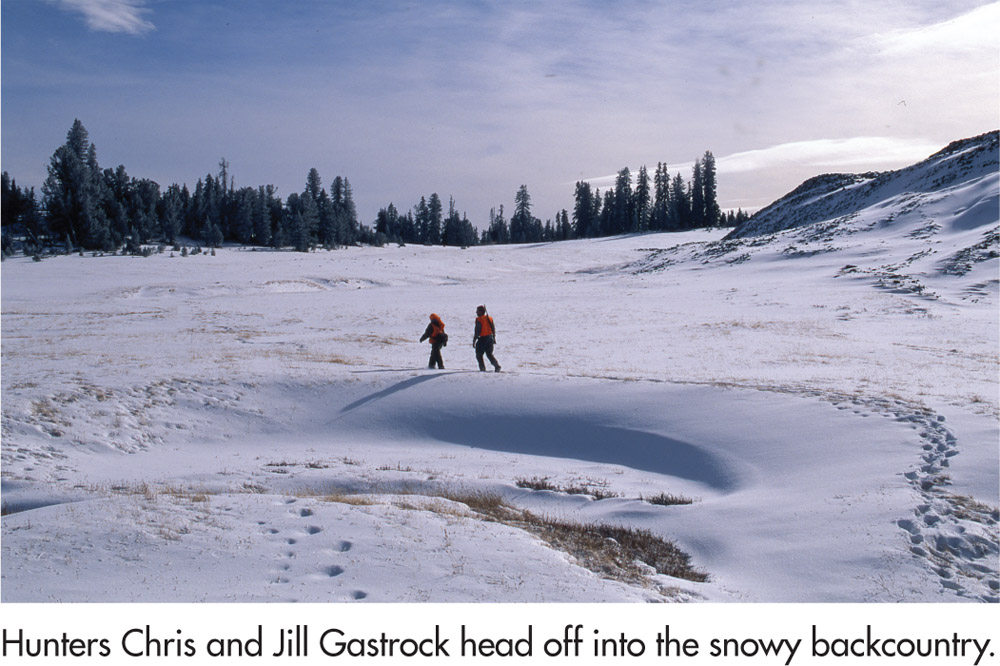

It may seem paradoxical, but there are probably more hikers who become lost or injured in the snow than there are people who engage in classic winter sports like snowmobiling, cross-country skiing, or snowshoeing. Thats simply because there are more hikers than there are pure winter recreationists, and its also true that hikers are probably less likely to be prepared for wintry conditions. Hunters can be grouped with hikers, and they are notorious for finding themselves in snowy predicaments.

Typically, most hikers start out in conditions of little or no snow. They often find themselves in trouble when they have hiked too far, especially after theyve hiked far enough to get into higher and snowier mountains, or if they are still out when the weather changes and it begins to snow. No matter how you arrive in a snow-related emergency, your comfort and perhaps even survival depend on the interrelated basic considerations of staying dry, staying warm, and staying hydrated and well fed.

Because hikers dont usually hike in extremely wintry conditions, its unlikely the snow will be either deep enough or consolidated enough to build emergency snow shelters like igloos or snow trenches. Given the likelihood that a lost day hiker wont have a tent or other portable refuge either, one of the best options for emergency shelter is a wickiup. Simply tie three relatively straight saplings together at the top, spread the poles out at the bottom, and then continue to add more poles to the basic tripod until the enclosure is complete (see photo). If a tarp is available, it can be draped over the outside of the structure as a shield from wind and water. If no tarp is on hand, progressively smaller-diameter poles can be added to the outside of the cone to seal off the enclosure, and foliated branches on the outside of the frame can make it even more air- and watertight. Leave a small gap in the perimeter to serve as a doorwaya small tarp, an extra garment, or a densely foliated shrub or branch can be used as a door flap after youve gone inside.

The size of the wickiup is determined, of course, by the length of the poles used to construct it. A small fire inside the wickiup will heat the whole structure. If possible, green poles and foliage make the best wickiup, as they are less likely to ignite from radiant heat or wayward sparks from the fire. The beauty of a wickiups conelike shape is that much of a fires heat will stay down low in the structure, where it will warm the occupants. Another tip: Its best if the inner poles of the structure are de-limbed and smooth. That way any seeping meltwater will tend to adhere to the poles and run down them to the ground rather than drip into the wickiups interior.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.