C ONTENTS

This edition published in the UK in 2017 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

www.iconbooks.com

Originally published in 2002 and 2003 by Icon Books Ltd

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia by

Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

7477 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia by

Grantham Book Services, Trent Road,

Grantham NG31 7XQ

Distributed in the USA by

Publishers Group West,

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

Distributed in Canada by

Publishers Group Canada,

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300,

Toronto, Ontario M6J 2S1

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand by

Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500,

83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by

Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

ISBN: 978-1-7857-8236-7

eISBN: 978-1-7857-8251-0

Text copyright 2002 John Henry

The author has asserted his moral rights

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means,

without prior permission in writing from the publisher

Dedication

For Rachel

A BOUT THE A UTHOR

John Henry is Professor Emeritus of the history of science at the University of Edinburgh. His interests lie in the history of interactions between science, medicine, magic and religion in the Renaissance and the early modern period. He is the author of Moving Heaven and Earth: Copernicus and the Solar system (2001, republished 2017), Religion, Magic, and the Origins of Science in Early Modern England (2012) and The Scientific Revolution and the Origins of Modern Science, 3rd edition (2008).

L IST OF I LLUSTRATIONS

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My interest in Francis Bacon was first kindled many years ago by Graham Rees and Julian Martin, two real Bacon experts, and Ive gratefully drawn upon their work, as well as their inspiration, in the writing of this. More recently, Ive been very grateful for long conversations with Silvia Manzo, an Argentinian scholar whose interest in Bacon testifies to his international reputation; it was good to be reassured, by another real Bacon expert, that my slant on Bacon wasnt too awry. I owe thanks also to Jon Turney, editor of this series, Simon Flynn at Icon Books, and John McEvoy, for excellent advice on how to make improvements.

Id also like to take this opportunity to thank, for general encouragement and friendship over the years, Stuart McLeod, Andy Pearson and Mike Wardman.

Francis Bacon saw a wife and children as hostages to fortune, but mine have done nothing but improve my fortune. Id like to thank my wife, Rachel, and my daughters, Eilidh and Isla, for their love and support, not just during the writing of this book, but always. Hoping therell be future books that I can dedicate to my daughters, I dedicate this book to my wife, with especial thanks for everything, and with love.

C HAPTER 1

K INDLING A L IGHT IN N ATURE

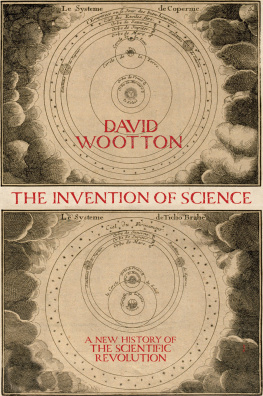

Francis Bacon was a great genius who helped to shape the modern world. But many people would be hard put to say exactly why. He made no new discoveries, developed no technical innovations, uncovered no previously hidden laws of nature. His achievement was to offer an eloquent account of a philosophy and a method for doing those things. And in that way he turned out to be as important as people famed for particular discoveries, like Galileo or Isaac Newton, in what historians now call the Scientific Revolution.

Essentially, Bacon (15611626) wanted to reinvent investigation of the natural world. He was dazzled by a vision of progress whose ambition knew no bounds, stemming from a conviction as strong as that of a later philosophical revolutionary, Karl Marx, that the point of philosophy was not just to interpret the world, but to change it. As Bacon saw it in one of his soaring flights:

[A]bove all, if a man could succeed, not in striking out some particular invention, however useful, but in kindling a light in nature a light which should in its very rising touch and illuminate all the border-regions that confine upon the circle of our present knowledge; and so, spreading further and further should presently disclose and bring into sight all that is most hidden and secret in the world that man (I thought) would be the benefactor indeed of the human race the propagator of mans empire over the universe, the champion of liberty, the conqueror and subduer of necessities (Proemium (Preface), Of the Interpretation of Nature, 1603).

In our terms, Bacon was a philosopher of science perhaps the first one who really mattered. He was driven to combine three concerns: how knowledge was justified, how it could be expanded and how it could be made useful. His new method was designed to transform completely the knowledge of the natural world of his day, which he saw as both misconceived and sterile. As he was also a great writer, he helped to inspire others to adopt a new attitude to natural philosophy, an influence that lasted long after his death in 1626.

Two hundred and fifty years later, for instance, Charles Darwin described the method of working that was to lead him to his theory of natural selection. It was, he said, perfectly Baconian.

After I returned to England it appeared to me thatby collecting all facts which bore in any way on the variation of animals and plants under domestication and nature, some light might perhaps be thrown on the whole subject. My first notebook was opened in July 1837. I worked on true Baconian principles, and without any theory collected facts on a wholesale scale (Autobiography, 1892, but written in 1876).

Darwin didnt strictly work like this. Nor has any other successful scientist, because you cannot collect facts in this undirected way without disappearing beneath a mountain of irrelevancies. But the fact that the mild-mannered Victorian scientific revolutionary saw fit to invoke the Elizabethan statesman and philosopher is one index of Bacons enduring fame. Another is the expectation we still hold, in a century when governments spend billions on research, that systematic experiment, conducted in a highly organised and institutionalised way, will yield useful answers to all kinds of problems from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) to global warming. Our idea of science as the endless frontier, as the American Vannevar Bush titled a report to the US government just after World War Two, is also Baconian in spirit.

More recently, though, as increasing numbers of people question the impact of science, Bacon has attracted as many critics as admirers. Some deny his influence or significance. Others who acknowledge his importance see his attitudes as baleful or pernicious, his writings as a call to seek the domination of nature, and male domination at that. But all this scholarly argument just makes it more important to get to know what he was about. The fact that Bacon was concerned not with making scientific discoveries but with the very nature of science itself seeking to establish what its purposes should be, the optimal methods for making discoveries, the best way to establish truth has not only ensured his place in history but also ensured that it is controversial.

After all, while the value of a specific invention or discovery might be immediately recognisable, claims about the best way of going about things are endlessly debatable. When the subject for debate is something as culturally important as modern science and technology, it is hardly surprising that Bacon has continued to divide opinion. But what critics of Bacon sometimes fail to realise is that he himself was instrumental in making science and technology such characteristic aspects of Western culture. Before Bacon there was no such thing as science in our modern sense of the word. After Bacon, Western Europe was set on a course of discovery and invention that was to result in a civilisation based on the power of science and technology. In a very real sense, therefore, Bacon invented modern science.