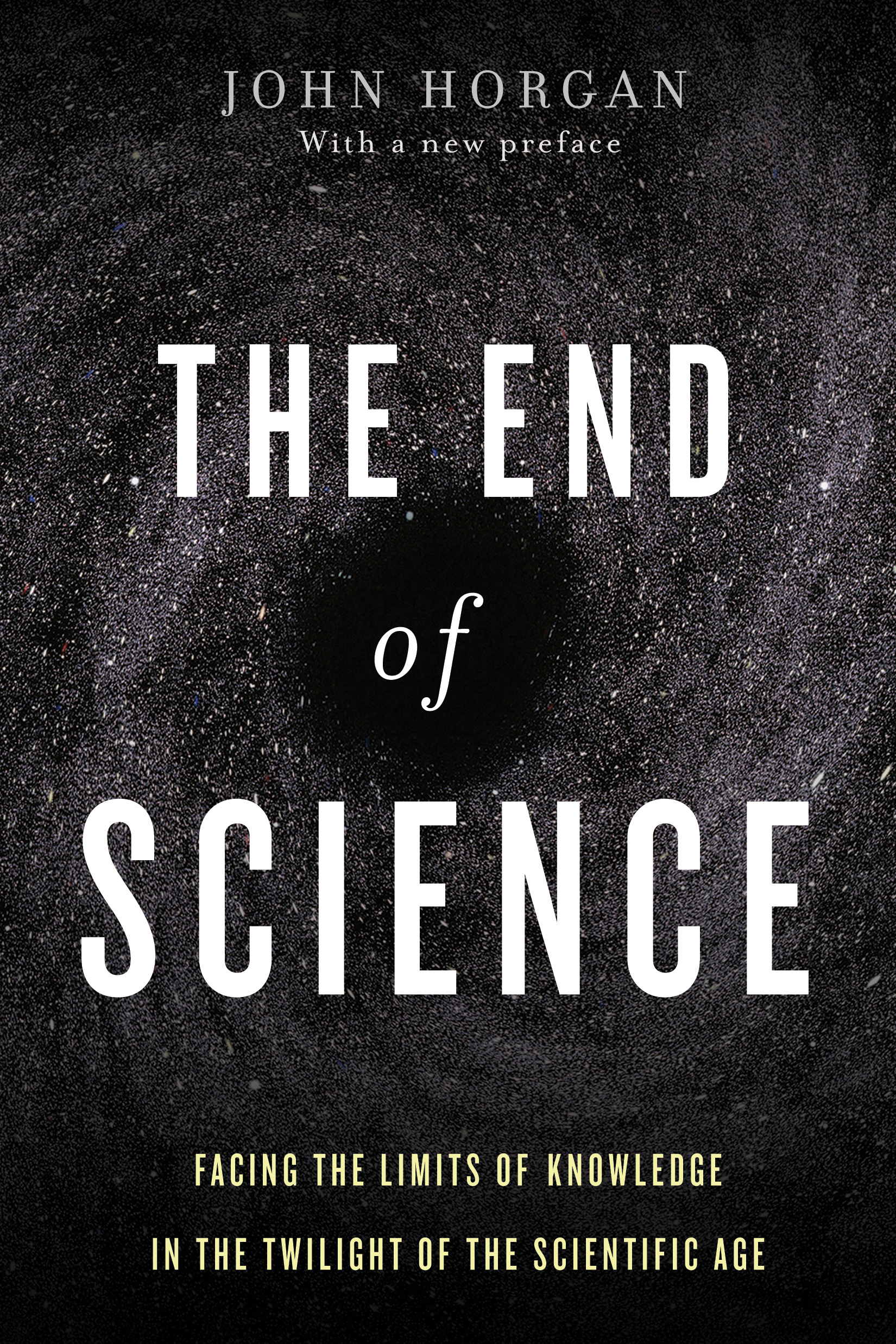

Praise for John Horgans

The End of Science

In this wonderful, provocative book... Horgans approach is to take us along while he buttonholes several dozen of earths crankiest, most opinionated, most exasperating scientists to get their views on where science is and where its going.... They all come to life in Horgans narrative.

Washington Post Book World , front page review

Thanks to Mr. Horgans smooth prose style, puckish sense of humor, and wicked eye for detail, these encounters make for zesty reading. Frequently they are hilarious.... A thumping good book .

Wall Street Journal

A deft wordsmith and keen observer , Horgan offers lucid expositions of everything from superstring theory and Thomas Kuhns analysis of scientific revolutions to the origin of life and sociobiology.

Business Week

[The books] greatest pleasures flow from Horgans encounters with the characters who have made science their lives.

San Francisco Chronicle

Rich in provocative ideas and insightful anecdotes.

Library Journal

The End of Science , a lively, witty book by science writer John Horgan, exemplifies the genres virtues and faults: It is fun to read. It will make people think .

Reason

It is a sweeping argument, admirably brought off .

Washington Times

John Horgan has everybody talking . Probably no science book of this year has generated as much comment.

Rocky Mountain News

The End of Science is a revealing glimpse into the minds of some of our leading scientists and philosophers. Read it. Enjoy it, learn from it .

Hartford Courant

The End of Science

The End

of

Science

Facing the Limits of Knowledge in the Twilight of the Scientific Age

John Horgan

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

New York

Preface to the 2015 Edition copyright 2015 by John Horgan

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and the publisher was aware of the trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For more information, address the Perseus Books Group, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, New York 10107.

Books published by Perseus Books are available for special distribution for bulk purchase in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Text design by Jack Lenzo.

A CIP catalog record for the original paperback edition of this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-0-465-05085-7 (ebook)

A hardcover edition of this book was originally published in 1996 by Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc.

Copyright 1996 by John Horgan.

First trade paperback edition published 1997 by Broadway Books.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Dad

Contents

Roger Penroses ambivalence toward The Answer.

The difference between science and literary criticism.

The anxiety of scientific influence.

What is ironic science?

A meeting on the end of belief in science.

Gunther Stents Golden Age.

Is science a victim of its own success?

What physicists really thought 100 years ago.

The apocryphal patent official.

Bentley Glass casts doubt on Vannevar Bushs endless frontier.

Leo Kadanoff sees hard times ahead for physics.

Nicholas Reschers wishful thinking.

The meaning of Francis Bacons plus ultra.

Ironic science as negative capability.

What the skeptics really believe.

Karl Popper finally answers the question: Is falsifiability falsifiable?

Thomas Kuhn is hoist on his own paradigm.

Paul Feyerabend, the anarchist of philosophy.

Colin McGinn pronounces philosophy dead.

The meaning of the Zahir.

Sheldon Glashows doubts.

Edward Witten on superstrings and aliens.

The pointless final theory of Steven Weinberg.

Hans Bethes doomsday calculation.

John Wheeler and the it from bit.

David Bohm, clarifier and mystifier.

Richard Feynman and the revenge of the philosophers.

The infinite imagination of Stephen Hawking.

David Schramm, the big bangs biggest booster.

Doubts among the cosmic priesthood.

Andrei Lindes chaotic, fractal, eternally self-reproducing, inflationary universe.

Fred Hoyle, the eternal rebel.

Will cosmology turn into botany?

Richard Dawkins, Darwins greyhound.

Stephen Jay Goulds view of life: shit happens.

Lynn Margulis denounces Gaia.

The organized disorder of Stuart Kauffman.

Stanley Miller ponders the eternally mysterious origin of life.

Edward Wilsons fear of a final theory of sociobiology.

Noam Chomsky on mysteries and puzzles.

The eternal vexation of Clifford Geertz.

Francis Crick, the Mephistopheles of biology, takes on consciousness. Gerald Edelman postures around the riddle.

John Eccles, the last of the dualists.

Roger Penrose and the quasi-quantum mind.

The counterattack of the mysterians.

Is Daniel Dennett a mysterian?

Marvin Minskys fear of single-mindedness.

The triumph of materialism.

What is chaoplexity?

Christopher Langton and the poetry of artificial life.

Per Baks self-organized criticality.

Cybernetics and other catastrophes.

Philip Anderson on the meaning of More Is Different.

Murray Gell-Mann denies the existence of something else.

Ilya Prigogine and the end of certainty. Mitchell Feigenbaum is refuted by a table.

Pondering The Limits of Scientific Knowledge in Santa Fe.

A meeting on the Hudson River with Gregory Chaitin.

Francis Fukuyama disses science.

The Star Trek factor.

The out-of-sight prophecy of J. D. Bernal.

Hans Moravecs squabbling mind children.

Freeman Dysons principle of maximum diversity.

The bunkrapt vision of Frank Tipler. What would the Omega Point want to do?

A mystical experience.

The meaning of the Omega Point.

Charles Hartshorne and the Socinian heresy.

Why scientists are ambivalent toward truth.

Is God chewing his fingernails?

Rebooting The End of Science

H eres what a fanatic I am: When I have a captive audience of innocent youths, I expose them to my evil meme.

Since 2005, Ive taught history of science to undergraduates at Stevens Institute of Technology, an engineering school perched on the bank of the Hudson River. After we get through ancient Greek science, I make my students ponder this question: Will our theories of the cosmos seem as wrong to our descendants as Aristotles theories seem to us?

I assure them there is no correct answer, then tell them the answer is No, because Aristotles theories were wrong and our theories are right. The earth orbits the sun, not vice versa, and our world is made not of earth, water, fire and air but of hydrogen, carbon and other elements that are in turn made of quarks and electrons.

Our descendants will learn much more about nature, and they will invent gadgets even cooler than smartphones. But their scientific version of reality will resemble ours, for two reasons: First, oursas sketched out, for example, by Neil deGrasse Tyson in his terrific re-launch of Cosmos is in many respects true; most new knowledge will merely extend and fill in our current maps of reality rather than forcing radical revisions. Second, some major remaining mysteriesWhere did the universe come from? How did life begin? How, exactly, does a chunk of meat make a mind?might be unsolvable.