The fabulous faade of the Hui Kuan or Hokkien Clan Association in Malacca.

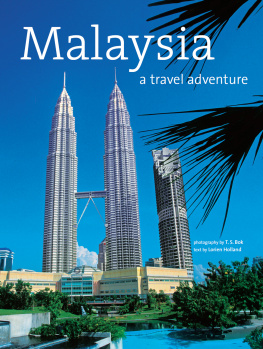

Malaysia:

The Original Melting Pot

A typical village house in Kampong Mortem in downtown Malacca. Its steep pitched roof is well suited for ventilation and tropical downpours. The ceramic tiles on the steps are a Portuguese-influenced style.

Long before New York became the melting pot of the New World, Malaysia was bubbling away, mixing cultures, religions and ways of life. From way back in the third century BC , when trading links were firmly established with China to the east and India to the west, Malaysia has been a fertile ground for the fusion of different faiths and ways of life. The result is a unique jumble of localized cultures involving aboriginals (Orang Asli), Malays, Chinese, Arabs, Sumatrans, Indians and Europeans, who have mingled and fought for control of trading rights and the countrys rich natural resources.

Underneath that mesh of beliefs and religions, Malaysia is a humid, tropical landscape, where frangipani trees grow by the roadside, inviting white sands separate the land from the sea and the jungles are so dense that animal and plant species are still being discovered within. Encroaching on that landscape is, of course, a fast-expanding urban environment of office blocks, highways, billboards and shopping malls as the modern state of Malaysia reaches towards its goal of developed nation status by 2020.

I was quite unprepared for the degree of modernity in present-day Malaysia when I moved there in the year 2000. I had seen photographs of Kuala Lumpurs icon to progress, the Petronas Twin Towers. My sister, a long-term resident of the city, had also briefed me on the changes afoot. But the state-of-the-art airport, the modern highways, the swish hotels, the highly air-conditioned upmarket shopping centres not to mention the traffic jams were way beyond my expectations.

Until recent decades, Malaysia, or Malaya as it was called in colonial times, really was a backwater. Time passed slowly, palm oil, tin and rubber were the major industries, and people had time to sit and talk as long as they were out of the sun and in the shade!

Still, the concept of time passing slowly should not be confused with time not passing at all. Malaysia has a very lengthy past. Human remains dating back some 37,000 years have been found in the Niah Caves in eastern Malaysia. More recent ancestors moved southwards from China and Tibet around 10,000 years ago and make up the bulk of the indigenous populations of Orang Asli today. Later migrants brought fishing and sailing skills with them, and gave their name to the Malay Archipelago lands which today make up the modern states of Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore and Brunei.

The Sultan Ahmad Samad Building at Dataran Merdeka (Independence Square) in the centre of old Kuala Lumpur. Once the centre of the colonial administration, the building now houses the commercial division of the High Court.

The pink granite Putra Mosque is at the centre of the new administrative capital of Putrajaya. Completed in 1999, the mosque can accommodate 15,000 people and is an interesting blend of Islamic architectural and decorative styles from Malaysia, Persia, the Arab world and Kazakhstan.

Malaysias geographical position at the crossroads between civilizations and trading routes meant outside influences were always strong, and often hard to resist. After the arrival of the Malays, there were four main waves of foreign influence and conquest, which eventually split the Malay Archipelago into separate political entities. This is not hard to understand when you see that Hindu India, the Islamic Middle East and Christian Europe lie to the west. To the northeast are Buddhist China and Japan; and the shipping routes linking them all pass right around modern Malaysia and through the Strait of Malacca.

Dancers holding the Malaysian flag at the annual National Day parade in downtown Kuala Lumpur.

An aerial view of the heart of Kuala Lumpur. The large green rectangle is Independence Square, once the heart of the colonial administration when it was known as the Padang. The mock Tudor-style Selangor Club is on its left and the Sultan Abdul Samad Building on its right. The triangle of green is the confluence of Kuala Lumpurs two rivers and the point where the city started.

The startling variety of food in Malaysia is a good illustration of these differing cultural streams. From the majority Malay population comes spicy coconut and lemon grass-based cuisine. Southern Indian, Hainanese, Cantonese, Hakka, Javanese, Sumatran, Middle Eastern and Portuguese foods all have large followings. There is even the celebrated Nyonya style, which is a mixture of Chinese and Malay cooking. And every so often youll be offered a watery cucumber sandwich and a stiff cup of tea in a nod at British colonial rule.

The first major outside influence on the Malay-speaking world came from Indian and Chinese traders. The monsoon winds meant vessels had to pass down the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia, round the tip and past what is now Singapore, and up the other side through the Strait of Malacca. Indian influence was particularly strong, and old documents speak of Indian traders buying timber and jewels from the Malays.

By the first century AD , both Hinduism and Buddhism were well established in these coastal enclaves, and Chinese chronicles speak of a great port in the Strait of Malacca in the fifth century AD . Two hundred years later, the maritime kingdom of Srivijaya rose to strength, and controlled the coasts of Sumatra, Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo. The maharajahs of Srivijaya waxed and waned, but stayed in power for 700 years by controlling the spice trade through the region.

Records of the time are sparse, but a possible early capital currently under exploration is Kota Gelanggi, in the jungles of southern Malaysia near to Singapore. Other outposts were in northern Malaysia, while most of the kingdom was focused on Palembang on the north coast of Sumatra. Srivijaya came under increasing attack from others who wanted to tax the lucrative spice trade. The fatal blow came in the middle of the fourteenth century from the Hindu Majapahit empire from eastern Java.

This is really the point where todays Malaysian school children start their history lessons. A rebel prince called Parameswara escaped from Srivijaya when the empire fell and headed north, eventually establishing a coastal fiefdom around 1400. This was Malacca (Melaka in Malay), which quickly became the most important port in Southeast Asia, controlling the lands on both sides of the Malacca Strait and all the lucrative spice trade that passed through.