About the Book

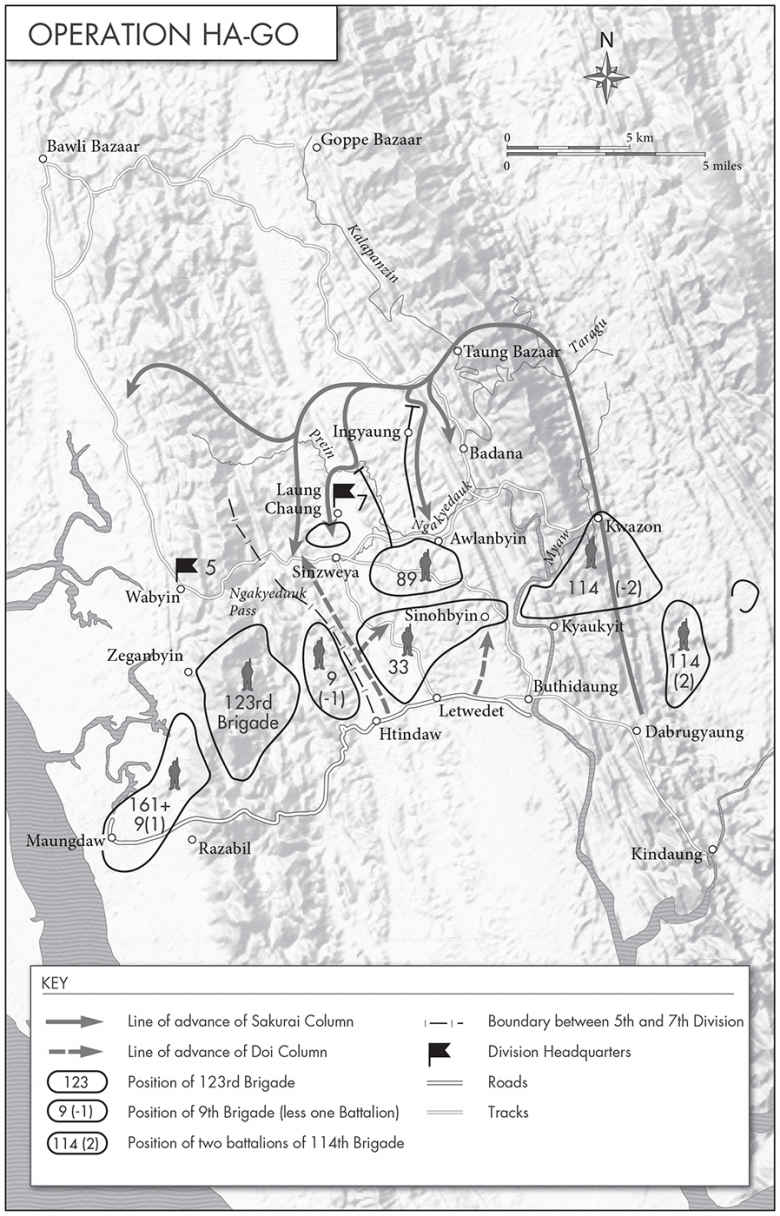

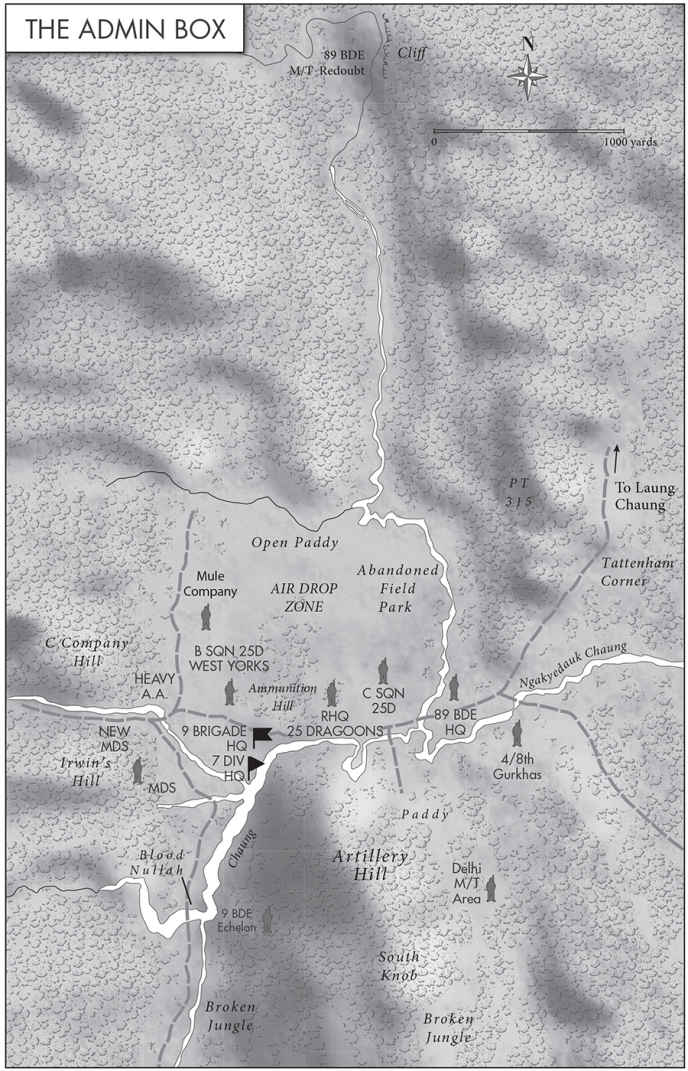

In February 1944, in one of the most astonishing battles of the Second World War, a ragtag collection of clerks, drivers, doctors and muleteers, a few dogged Yorkshiremen and a handful of tank crews used whatever means necessary to defeat a huge and sophisticated contingent of the fearsome and previously unvanquished Japanese infantry on their march towards the prize of India.

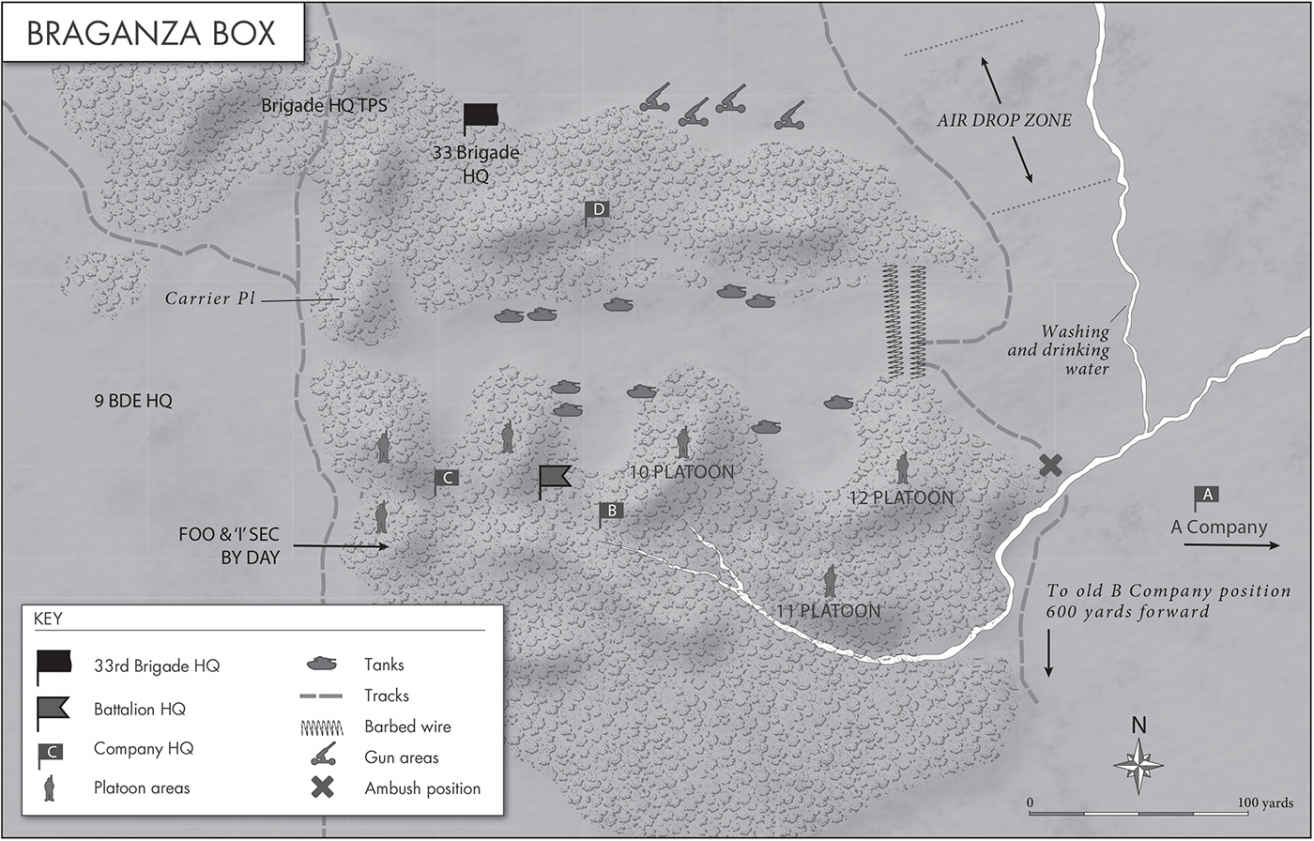

For over fifteen days, what became known as the Battle of the Admin Box was fought in the paddy fields and jungle of northern Arakan and ultimately turned the battle for Burma. Not only was it the first decisive victory for the Allies but, more significantly, it demonstrated how the Japanese could be defeated. Lessons learned in this tiny and otherwise insignificant corner of the Far East would underpin the campaign in Burma as General Slims Fourteenth Army turned the tide of the war in the East.

Burma 44 is a tale of incredible drama. As gripping as the story of Rorkes Drift, as momentous as the battle for the Ardennes, the Admin Box was a triumph of human grit and heroism and remains one of the most significant yet undervalued conflicts of World War Two.

Contents

For Harry Swan

List of Maps

Introduction

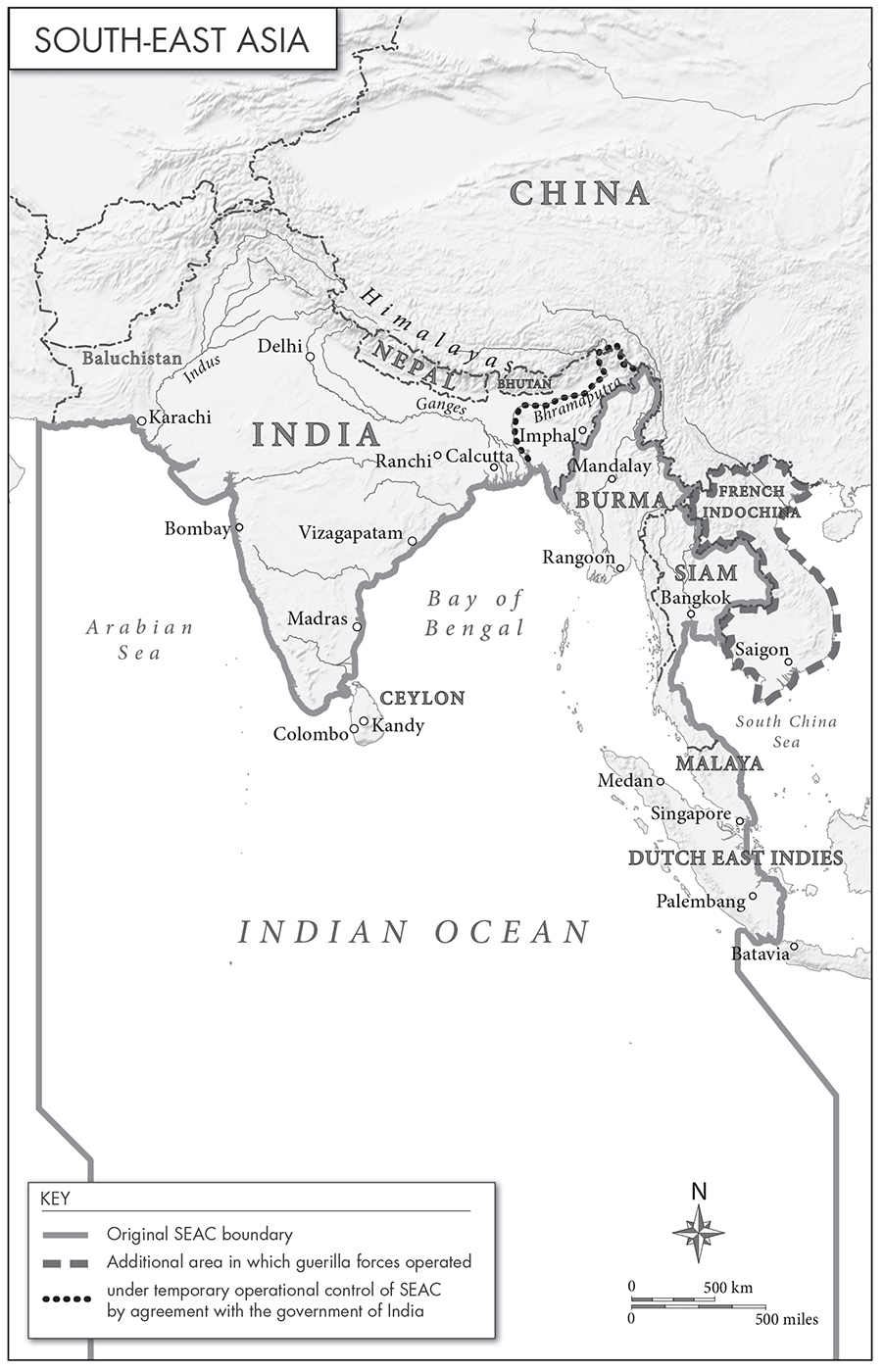

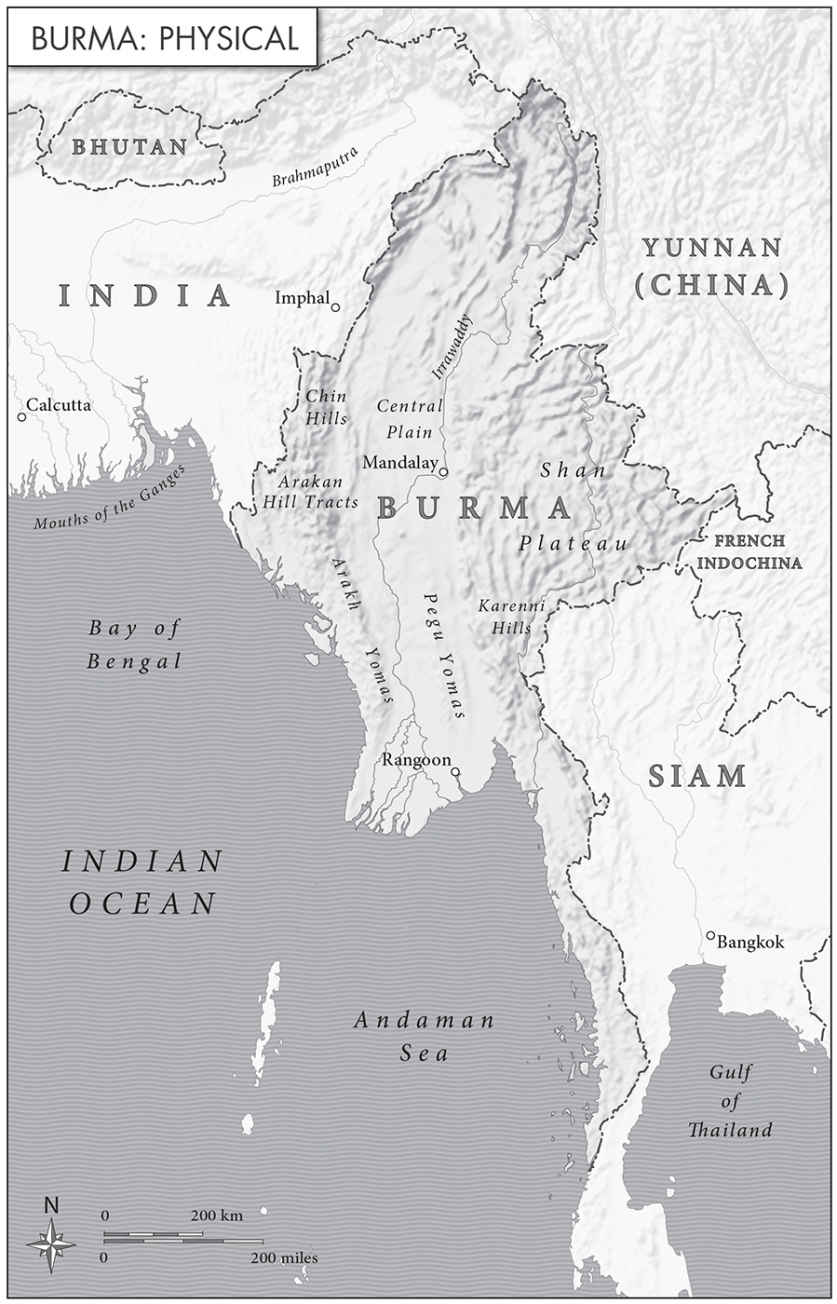

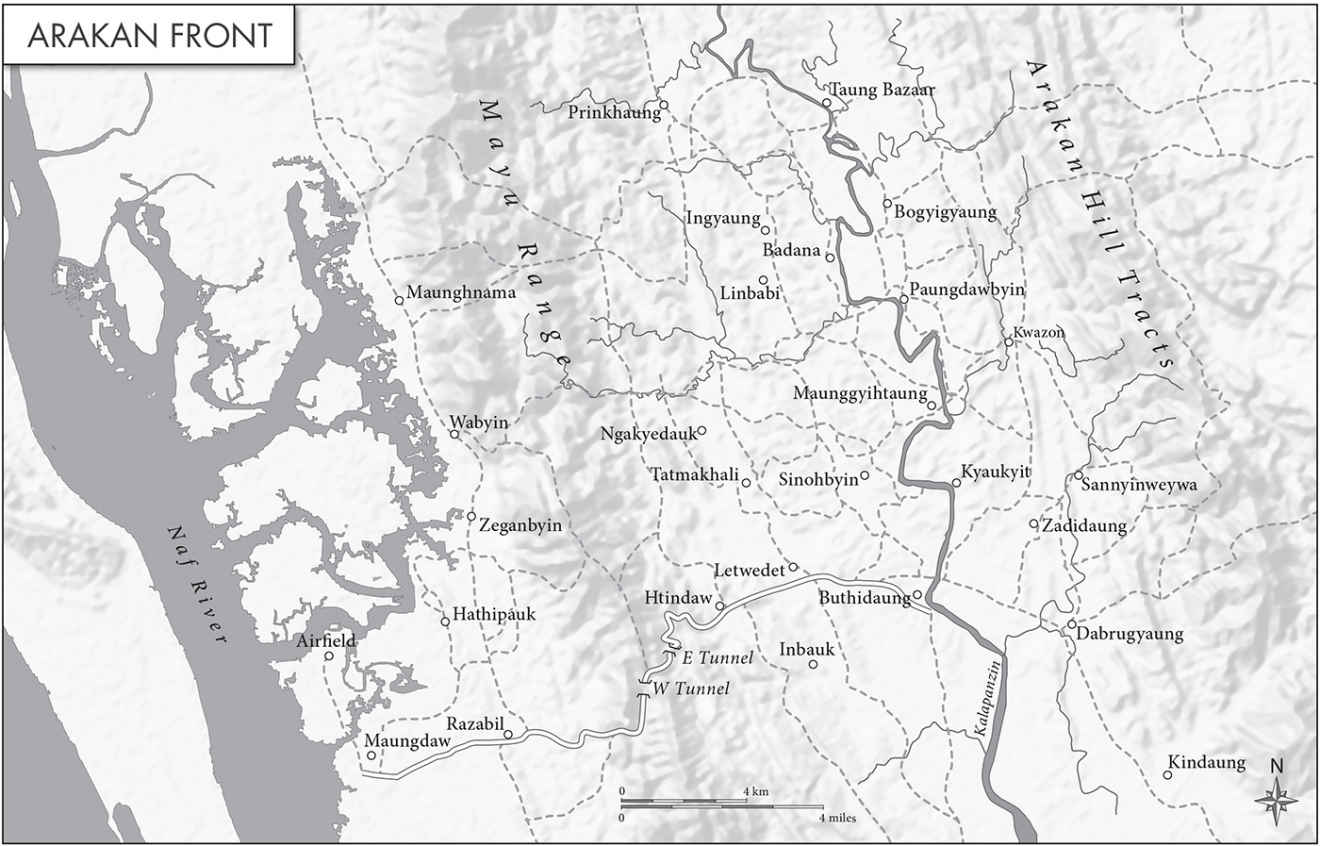

THE ARAKAN, NORTH-WEST Burma: a place of exotic beauty. Dense, lush jungle covered much of its long, jagged ridges and softer, rounded hills. It was home to a dazzling array of birds, insects and beasts, from swinging monkeys and baboons to tigers and elephants. Between the hills were a myriad valleys, and even patches of open plain with the occasional small settlement. For the most part, however, the Arakan was a large and remote hinterland, criss-crossed with a few jungle tracks, almost completely free from modernity. Part of it had never even been mapped. There were hardly any roads, not least because most Arakanese lived on the coast, which was indented with innumerable curling rivers draped with mangrove and palms, and where the only real means of transport were boat and raft.

Here, in this land of hill and jungle, the monsoon that ran from May to November brought thick, purple clouds that rolled over and dropped more rain than almost anywhere else in the world. Even the dry season was never dry for long, but between the torrents the sun beat down with a fierce intensity that sapped energy and drained the body dry. Beautiful it may have been, but it was a deadly, hostile beauty a place of terrible diseases, lethal snakes and insects, of flash floods and draining heat. Danger lurked in every shadow. Simply living in the sparsely populated Arakan was hard enough, but as a place to fight a war it was brutal.

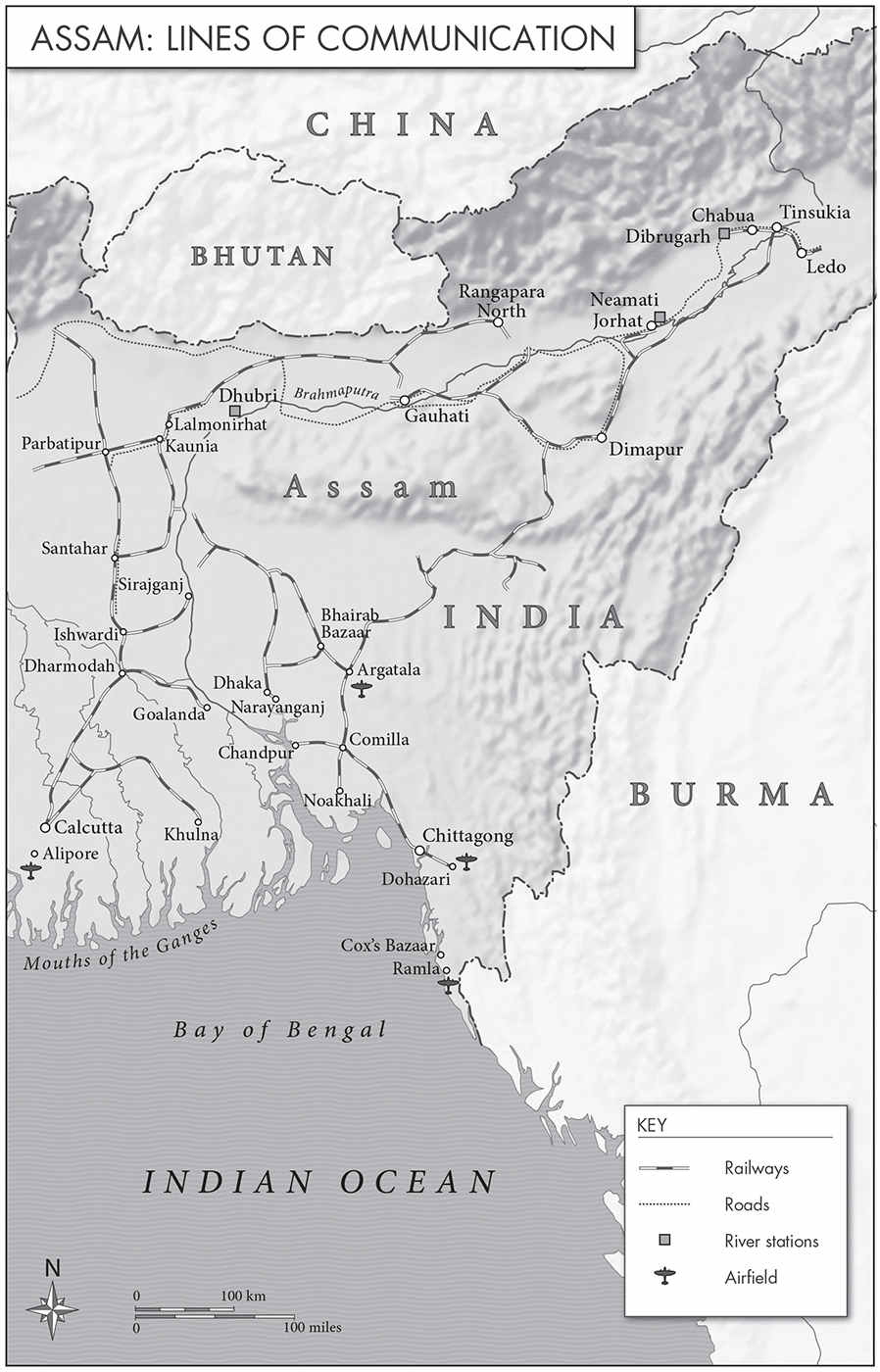

Yet it was in the Arakan, along the coastal strip, that one of only three possible routes into India lay and certainly the most direct, for the others lay hundreds of miles to the north-east, across the Imphal Plain and into Assam. Bengal, on the other hand, bordered the north-west of Arakan. And Bengal had a railway and even roads, as well as the large port of Chittagong. However hostile a place the Arakan may have been, it was still the obvious place through which to advance into India or drive south and east back into the rest of Burma. This gave it critical strategic importance, and consigned all those misfortunate enough to have to fight there to finding themselves caught up in a war zone in which they were invariably sodden either from sweat or rain blighted with insect bites and sores, where they would inevitably, sooner or later, be struck by malaria, dysentery, beri-beri or some other horrible illness, and where, because of the close nature of the terrain, the fighting was often hand to hand. Every rustle, snap of a twig or brush of bamboo could be a jungle animal or it could be enemy troops about to pounce. It is hard to think of a more terrifying or physically and psychologically draining place in which to fight.

I first came across the now largely forgotten Battle of the Admin Box some years ago and it reminded me a little of that epic battle at Rorkes Drift back in January 1879. The difference was that the Zulu Wars were provoked entirely by British imperialism and the attackers had every right to try to push the defenders out of Zululand. One can argue over whether Britain had any more right to be in Burma in 1944 than they had in that corner of South Africa sixty-five years earlier, but there can be no doubting that the particularly violent and sadistic Imperial Japanese regime was one that needed to be stopped at all costs. The Japanese treated their prisoners and the Burmese people they conquered absolutely abominably and, no matter how much many wanted British rule in India to end, conquest by the Japanese would have been utterly terrible.

At the start of 1944, the British forces in South-East Asia had yet to inflict any kind of defeat on the Japanese; in fact, they had suffered one humiliation after another. The pressure was on General Bill Slims Fourteenth Army somehow to turn their fortunes around. An offensive was planned in which Slim hoped to push the enemy south through the Arakan, but the Japanese stole his march and suddenly one of his key divisions found themselves entirely surrounded and staring down the barrel of a catastrophic and far-reaching defeat which threatened to undo the entire British situation not only in the Arakan but in Bengal as well.

This is the incredible story of that defiant stand and how British fortunes were, over the course of eighteen long and bitter days of horrific fighting, finally turned around. The feats of human endurance and stoicism in the midst of a barbaric battle of sustained fear and terror are truly awe-inspiring.

I am very conscious, though, that this story is told predominantly through the perspective of a handful of largely British participants. Sadly, testimonies of Indians, Gurkhas and even Japanese veterans, whether from diaries, letters, memoirs or oral histories, either barely exist or not in the kind of depth I needed; theirs is a generation that is slipping away all too fast and it is tragic that so many of them have never had the chance to have their memories recorded.

As a result, this is an account of a battle told through the eyes of just some of those who were there. It is meant to be nothing more than a narrative of an extraordinary episode in that long, bitter struggle in South-East Asia. It is a period of the war which, although perhaps familiar in its overview, remains curiously forgotten in its detail; and so I hope that even though one-sided in its telling, this book will, at least, shed some light on the experiences of British servicemen who fought in this toughest of campaigns.