Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

constitute an extension of this copyright page.

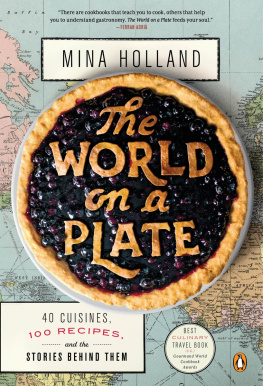

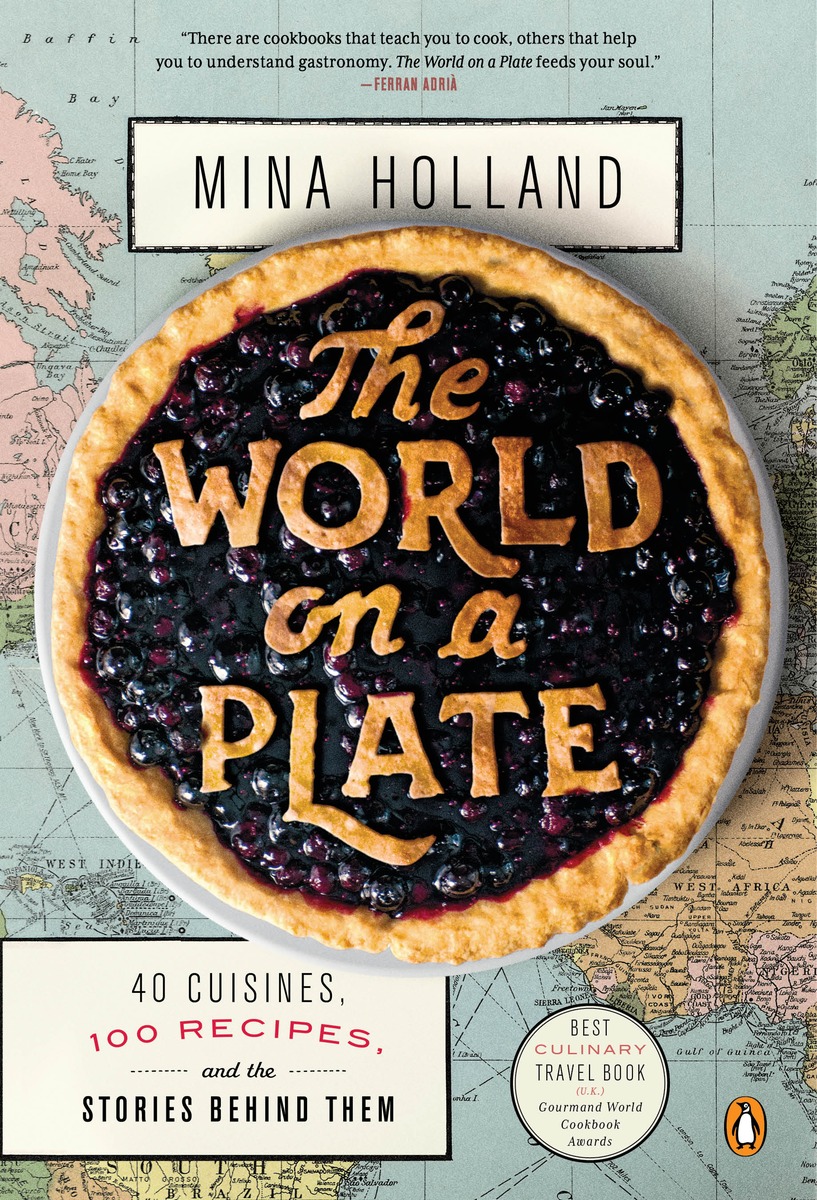

Holland, Mina.

The world on a plate : 40 cuisines, 100 recipes, and the stories behind them / Mina Holland.

1. International cooking. 2. FoodHistory. 3. Food habits. I. Title.

The recipes contained in this book are to be followed exactly as written. The publisher is not responsible for your specific health or allergy needs that may require medical supervision. The publisher is not responsible for any adverse reactions to the recipes contained in this book.

INTRODUCTION

It is not just the great works of mankind that make a culture. It is the daily things, like what people eat and how they serve it.

LAURIE COLWIN, Home Cooking

WHEN WE EAT, we travel.

Think back to your last trip. Which are the memories that stand out? If youre anything like me, meals will be in the forefront of your mind when you reminisce about travels past. Tortilla, golden and oozing, on a lazy Sunday in Madrid; piping hot shakshuka for breakfast in Tel Aviv; oysters shucked and sucked from their shells on Whitstable shingle. My memories of the things I saw in each of those places have acquired a hazy, sepia quality with the passing of time. But those dishes I remember in Technicolor.

As Proust noted on eating a petit madeleine with his tea, food escorts us back in time and shapes our memory. The distinct flavors, ingredients and cooking techniques that we experience in other spaces and times are also a gateway to the culture in question. What we ate in a certain place is as important, if not more so, than the other things we did therevisits to galleries and museums, walks, toursbecause food quite literally gives us a taste of everyday life.

Whenever I go abroad my focus is on finding the food most typical of wherever I am, and the best examples of it. Food typifies everything that is different about another culture and gives the most authentic insight into how people live. Everyone has to eat, and food is a common language.

The late, great American novelist and home cook Laurie Colwin put everyday food alongside the great works of mankind in making a culture. I have to agree. A baguette, the beloved French bread stick, is the canvas for infinite combinations of quintessential Gallic flavors (from cheese to charcuterie and more). It is steeped in history and can arguably tell you more about French culture than Monets lilies. Moroccan food expert Paula Wolfert, a beatnik of the 1960s who flitted from Paris to Tangier with the likes of Paul Bowles and Jack Kerouac, also relates to Colwins words. Food is a way of seeing people, she once said to mesuch a simple statement, but so true. Unlike guidebooks and bus tours, food provides a grassroots view of populations as they live and breathe. When we eat from the plate of another culture, we grow to understandmouthful by mouthfulwhat it is about.

Eating from different cultures is not just a way of seeing people: it can train a different lens on the food itself, too. I started eating meat again a few years ago after twelve years of being a (fish-eating) vegetarian. But while I was happy to try all sorts of cuts and organs, lamb still troubled me. Ive loathed the fatty, cloying scent of roasting lamb since I was a child, an aversion that had become almost pathological. When I met Lebanese cook Anissa Helou for the first time, I casually slipped my antipathy for lamb into the conversation. Her jaw dropped. She told me this was impossible, that I couldnt write a book about the worlds food without a taste for lamb. A few months later I was at her Shoreditch apartment eating raw lamb kibbeh (see page ) was also a revelation. Ingredients take on different guises in other cuisines, and this can transform our perception of them.

In recent years food has assumed a status analogous to film, literature and music in popular culture, expressing the tastes of society in the moment. Food manifests the zeitgeist. There are now global trends in food. In cosmopolitan cities from London to New York, Tokyo to Melbourne, crowds flock to no-reservations restaurants that serve sharing plates against a backdrop of distressed dcor, or to street-food hawkers selling gourmet junk food and twee baked goods. Todays most famous food professionalsfrom the multi-Michelin-starred Ren Redzepi to neo-Middle Eastern pastry chef Yotam Ottolenghi and TV cook Nigella Lawsonare another facet to celebrity culture. They prize creativity in the kitchen, drawing on many different culinary and cultural influences to make dishes that are unique to them, for which societys food lovers have a serious appetite.

Amidst this enthusiasm for food and the growing fascination with culinary trends (which seem to change as frequently as the biannual fashion calendar), there are gaps in our knowledge about pedigree cuisines. Self-proclaimed foodies may know who David Chang is, proudly order offal dishes in restaurants or champion raw milk over pasteurized alternatives, but can they pinpoint what actually makes a national or regional cuisine? How do you define the food of, say, Lebanon or Iran? What distinguishes these cuisines from one another? What are the principle tastes, techniques of cooking and signature dishes from each? In short, what and why do people eat as they do in different parts of the world?

Taking you on a journey around forty world cuisines, my aim is to demystify their essential features and enable you to bring dishes from each of them to life. Remember: when we eat, we travel. Treat this book as your passport to visit any of these places and sample their delicaciesall from your very own kitchen.

WHAT IS A CUISINE?

AMERICAN ACADEMIC-CUM-FARMER Wendell Berry once said that eating is an agricultural act, drawing attention to the fact that what we eat in a given place reflects the terrain and climate where local produce lives and grows. But this is an oversimplification, taking only geography into consideration.

In fact, a cuisine is the edible lovechild of both geography and history. Invasions, imperialism and immigration solder the influence of peoples movement onto the landscape, creating cuisines that are unique to the place but, by definition, hybridlike that of Sicily, where the Greeks, Romans, Normans, Arabs, Spanish, French and, most recently, Italians have all had their moment of governance. Today, Sicilian dishes express both the peoples that have inhabited the island and the rich Mediterranean produce available there.