This memoir reflects the authors life faithfully rendered to the best of her ability.

Cover copyright 2017 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

First U.S. Trade Paperback Edition: February 2017

Twelve is an imprint of Grand Central Publishing.

The Twelve name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBNs: 978-1-4555-3769-3 (trade paperback); 978-1-4555-3768-6 (ebook); 978-1-4789-6276-2 (audiobook downloadable)

W e have begun what has grown into a daily ritual. It starts with me taking my mornings thrill-seeking taxi ride through the crowded streets of Yazd, to her apartment complex on the edge of the city. Normally each morning, I ask the driver to stop on the way to buy flowers and he frets impatiently as I pick through the wilted irises and tulips that have somehow found their way to this place in the desert. But this mornings driver makes me uncomfortable, so I dont ask him to stop.

Older than the other taxi drivers Ive had, he isnt sporting the latest gelled-up, parrot hairstyle. No sun-bleached, hand-lettered taxi sign is strapped onto the roof of his car. Despite the ninety-degree weather he is wearing a jacket over a thick, coarse-wool sweater. His car smells faintly of rosewater and tobacco.

As he drives he clacks a string of wooden prayer beads loudly between his fingers. The dashboard is taped up with worn prints of bearded prophets in fading shades of green. He is the kind of devout, unsmiling man I can still feel intimidated by.

He is silent during the twenty-minute journey from where he picked me up, honking and swerving his battered Paykan to where Id stood at the curb. This is likely a second job, carried out for a few hours each morning, the consequence of rising inflation and three currency devaluations in the last year alone.

I reach down to fidget with the length of rust-colored cotton resting in my lap from the scarf that loosely circles my head. A new habit picked up quickly. A green-handled screwdriver jammed into the gap next to my window rattles as we turn down the dusty, wide road lined with sand-colored brick buildings where Vahid lives with his parents. I hand over the equivalent of ten dollars, more than double what the trip should cost, and know enough not to wait for change.

In the three days that I have been coming here the guards have quickly learned my face. They look up from their newspapers to wave me through the entrance and up the stairs.

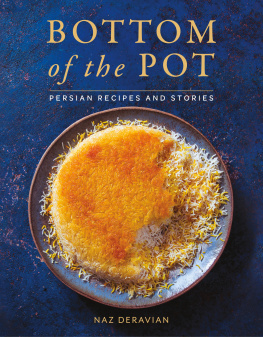

Vahids mother wears black every day. I want to greet her with a hug but its still too soon. She keeps her scarf on each time I come and lowers her head when I try to take photographs. Over cups of cinnamon tea we thumb through our combined collection of cookbooks to plan the days menu: chicken in pomegranate and walnut sauce or a fish stew fragrant with fenugreek and tamarind, the latter a specialty of her native Khuzestan.

We sit on the floor with a silver tray between us, sorting through mountains of fresh mint, basil and parsley. I rip away roots knotted with sand and tiny pebbles, and slosh the leaves through a bucket of salt water. She tears the skins from a pile of onions and slices them in her hand. Her small knife strikes against her palm and neat, tidy crescents fall away into a plastic bowl. She measures rice, dipping a chipped cup rimmed with gold and patterned with roses that lives inside the bag for exactly this purpose. Four cups full instead of three, because I am still considered a guest and it would be a great shame if I were not given extra when the meal is served.

I can sense by the way she smiles at me and her deep sighs of akheish that I am tipping the balance in this house. I imagine shes been missing the presence of her only female child. Vahids sister lives near the Iraqi border, twenty-six hours away by bus. She hums while we work, a humming that sounds too powerful for her slight build, a humming that sounds neither calming nor cheery. Instead, it wafts around me in a way that keeps me aware of her presence, a center of gravity in the kitchen we share.

Neither Vahid nor his father says much to her during our long mornings cooking together. Instead they attempt rudimentary repairs. The enormous cooler is removed from where it hangs suspended from the ceiling. They pry the filters loose with screwdrivers and take them to the balcony to bang them free of dust. Their tasks are social, involving long consultations with neighbors and the seeking of advice. Hers is solitary, the work of the sole woman of the house. They enter the kitchen only to reach around her to steal a peeled carrot from a bowl or a stray piece of cauliflower. Otherwise I see them only at mealtimes when they return from outdoors or rise from their places on the scarlet and navy carpet to throw open the door to the daily tide of relatives who wash in at lunchtime.

Each day, as the house fills with the aroma of saffron, pomegranate syrup or onions fried in butter, our work is not unlike that of some ancient royal court. We decorate each dish with swirls of cream and stripes of chopped herbs. We snap the sofreh tablecloth sharply in the air. Without speaking, we glide our palms over it in a coordinated motion, smoothing any creases from its gold-threaded pattern after laying it on the floor. We cover it with platters of rice flecked with barberries, bowls of fragrant stews and little jars of the homemade pickles labeled in her hand. The men are quick to sit, eating everything almost without speaking, their eyes glued to the television. As their plates empty they are automatically refilled by their wives. Scraps of fire-singed bread are set before them; the handle of the doogh pitcher, the drinking yogurt Vahids mother leaves on the window ledge each night to ferment and turn fizzy, is turned toward them for their easy reach. In this house life quietly arranges itself around the men who watch CNN and the BBC.

I half listen but I am not so interested. The reporter is talking about the upcoming elections. Ahmadinejad is making a speech. As the men struggle to understand the English voiceover they attempt loud interpretationsa commentary of pointing and shouting, with mouths half full of the food we have cooked. No one thinks to ask me.

Vahids father is always the loudest. Down, down America.

Tea follows lunch. The pots and dishes are gathered up and brought to the kitchen. Leftovers are scraped into empty yogurt containers to be reheated for dinner, and plates and cutlery are piled into the sink. I roll up my sleeves to wash the dishes but Vahids mother shoos me away. She gestures that I should sit instead with the men; a treat for me. I glance at Vahids father and uncles who remain sitting on the floor, dislodging particles from their teeth with wooden toothpicks. I shuffle across the room toward an aunt instead. She and I take turns cutting a pile of oval