As it is written, Let all who are hungry come and eat. Nobody likes to dance on an empty stomach. If you give us borscht, fine. If not, Ill take knishes or kreplach, kugel or dumplings. Blintzes and cheese will suit me, too. Make anything you like, and the more the better, but do it quickly.

Sholom Aleichem, The Bubble Bursts (the second story of Tevye the Dairyman; 1899)

To my dad, who let me destroy a fridge-full of ingredients as a five year old.

To my mom, who can stick a chile relleno to the ceiling like no one else.

To my wife, whose lack of skills in the kitchen made me expand my own.

And to my friends John and Scott, who never seem to mind indulging in second dinner... or third dinner.

NZ

To Gracie and the family

MCZ

Contents

:

:

For me, Americas delis are, in the very best sense of the word, museumscollectively, a sprawling network of cultural institutions in which we can view and sample the edible artifacts that evolved within one particular New World immigrant population. As they surged ashore in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Jews of Europe, and of Eastern Europe in particular, brought with them a host of gastronomic preferences, kitchen techniques, lore, foods permitted and foods not permitted, and theories as to what constitutes a fit and proper diet. Romanians and Poles, Russians, Latvians and Lithuanians, Hungarians, Czechs, Germans, French, and other immigrants from dozens of nationalities settled in, each with its own history and its own ideas of what it wanted to find in markets and what it expected to encounter on its tables.

Almost from day one, processes of cultural change went, inevitably, to work. For example, the newcomers, living cheek by jowl with each other, were exposed to each others tastes and ways of preparing food. Further, they found themselves, in their various communities, spread from New York and Boston to Galveston, Santa Fe, and Seattle, brought face to face with local traditions, which would come, in time, to exert influences on the way that they ate. And, beyond all that, they discovered that the range of ingredients available to them was quite different from that of the world they had left behind; this, too, opened the door to change, as they were forced to find substitutes for what they could not get and to develop uses within their traditional culinary idiom for what was new.

Although the national foods continued to have some place within the homes of the Jewish immigrants, quite early on, other contrary social forces soon came into play. As with the American population as a whole, more and more immigrant women began to work outside the home, and traditional cooking skills were rapidly diluted or even lost. And the broader society, anxious to assimilate the new arrivals, took steps that served to accelerate the process of acculturation. Public schools began to provide lunches to the children of poorer immigrant families, and the food they served was mainstream Americantomato soup and macaroni and cheese, not borscht or knishes. The emergent field of home economics offered coursesfor adults and for children in the schoolsthat stressed American-style food. And cookbooks, such as the Settlement Cookbook , intended for the use of the newcomers, offered a mix of American home cooking and largely homogenized European dishes, most not identifiable with any particular tradition.

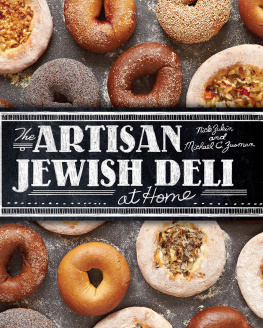

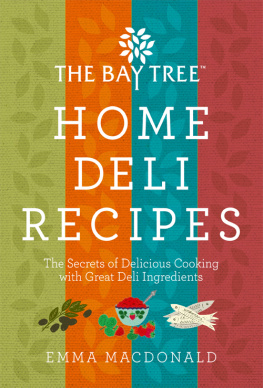

By World War I, although the tastes and the food memories remained in the immigrant communities, many women could no longer reproduce the old-time dishes, and more and more the specialties they knew were available only from butchers, bakers, and fish-mongers, and in a breed of retail shops known as appetizing stores or delicatessens. These outlets produced (or acquired from producers) their own versions of everything from kishke and pastrami to smoked whitefish, baked farmer cheese dotted with black pepper, and rugelach filled with walnuts and cinnamon. In time, such foods were also increasingly to be had in restaurants or at catered celebrations.

These new channels of accessibility were certainly of real value in preserving what might have been lost completely, but at the same time the entire body of foods was taking on a new character. First, most of the new entrepreneurs were not particularly concerned with the regional and local differences that had served to make Jewish food a richly varied folk cuisine. The resulting deli food was a little bit of Romanian, a little bit of Polishan amalgam of food traditions, perceived broadly as Jewish but not further identified. Second, this generalizing process was accompanied by the active incorporation of elements taken from the culinary milieu of the host countryfoods that did not originate in the world of the Jewish Europe but were nonetheless welcomed by the nostalgia-seeking second generation with the kind of enthusiasm they were beginning to feel for the dishes of their parents and their grandparents. Now included on the menu could be found a welter of deli foods including hot dogs, Reuben sandwiches, scrambled eggs with lox, sticky buns, Danish pastry, all washed down with Dr. Browns Celery Tonic (later to be known as Cel-Ray). Third, by the end of World War II, one of the most fundamental features of delikosher observancebegan to fade. In many establishments, cheeseburgers appeared on the menu, along with shrimp salad and challah French toast served with a side of bacon. A crucial link with the past was being severed.

But something else was going on as well. Many of those who made themselves the custodians of this peculiar mishmash of Jewish food also did with their loosely traditional cuisine just what is done by good cooks everywhere: they sought to improve, to innovate, to bring fresh thinking to old models. Cooking does not stand still any more than does language or science or the arts. Whether passively through the natural processes of evolution or more actively by playful riffing or earnest experimentation, change does happen, and more power to the people here who are willing to try, to adventureto look for what is better rather than for what is dutifully the same as it always was.

So, as is true of almost every facet of our many American hyphenated cultures, pure and authentic this food is surely not. And while it is true that delis have been in decline in both number and in distinctiveness for some years, they are nowhere near dead, as this very valuable book attests. They remain with us as important museumsrepositories of many of the foods of the past, from pickled tongue to chopped liver made with real schmaltz, to matzo balls, whole-sour dill pickles, herring in cream sauce, and dozens of other gastronomic treasures. They surely do offer an atmosphere of appreciation for a tradition that has earned its right to be preserved. And they do offer inspiration for a new generation to begin making these foods once again, sometimes in new and fresh ways, but also, as always, with love, with care, and with a sense of the history of an amazing migration that arrived here empty handed. And when the arrivals found out that our streets were not, in fact, paved with gold, they dug deep, worked hard, and brought forth gold where none had been.

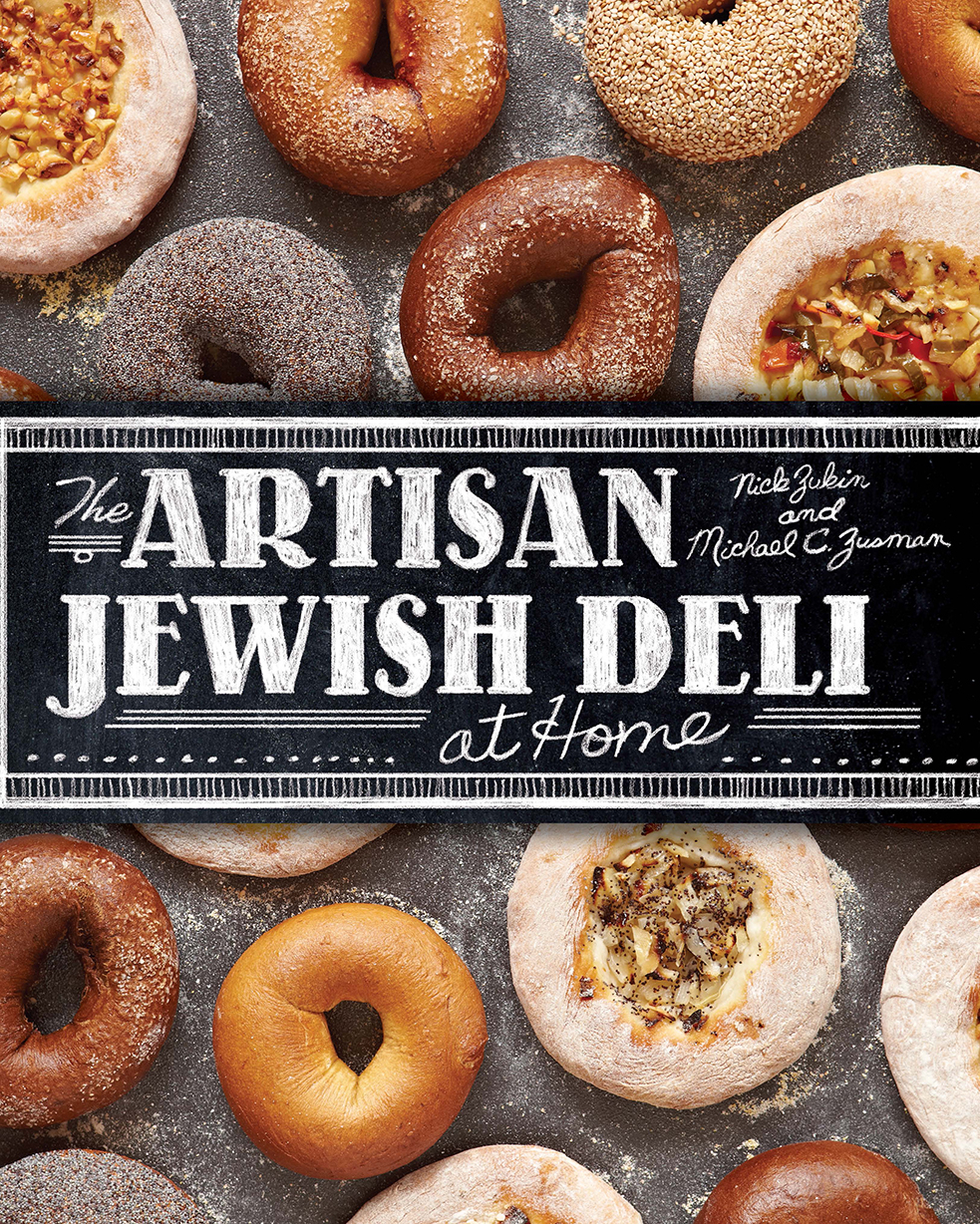

For all my true-blue Jewish credentials, I never considered myself religious, didnt keep kosher, and lacked even the foggiest notion about the history of the Jewish delicatessen. All I knew is that I liked the food: pastrami on rye; chewy, malty bagels with a schmear of cream cheese and topped with lox or smoked whitefish; blintzes; and potato latkes with a dab of sour cream. With the 2007 opening of Kenny & Zukes Delicatessenco-founded by Nick Zukin and partner Ken GordonI had a place to go in my Portland, Oregon, hometown to indulge my deli food fancy.