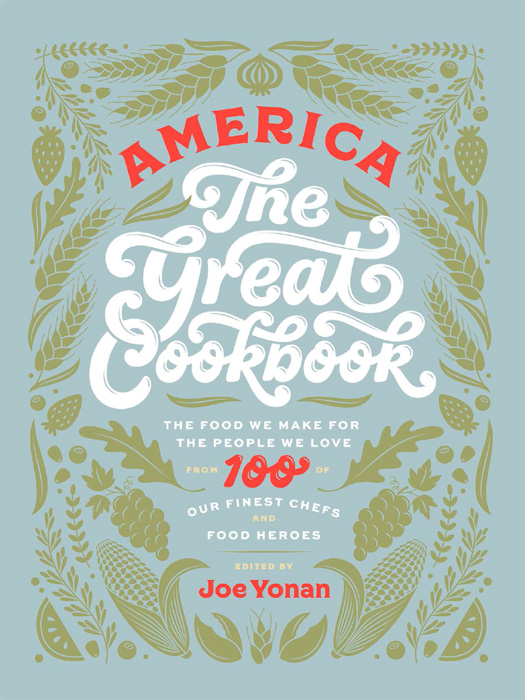

Joe Yonan is the two-time James Beard Awardwinning Food and Dining Editor of The Washington Post , and also writes the Post s award-winning Weeknight Vegetarian column. Originally from West Texas, Joe studied journalism at the University of Texas, Austin, and cooking at the Cambridge (MA) School of Culinary Arts. He is the author of two cookbooks, and writes regularly about his efforts to grow food on his 150-square-foot urban front yard. His work has appeared in four editions of the annual Best Food Writing anthology.

Introduction

When I was a kid growing up in West Texas in the 1970s, I loved Saturday mornings. Partly because I didnt have to go to school, of course, but also because of the cartoonsand because of Schoolhouse Rock! , a series of three-minute animated songs that ran between shows. Millions of us learned about legislative procedures through Im Just a Bill, math through Three Is a Magic Number, and grammar through Conjunction Junction.

Then there was the episode called The Great American Melting Pot. The chorus went: Lovely Lady Liberty/With her book of recipes/And the finest one shes got/Is the Great American Melting Pot. It was catchy enough, and the animation was striking: The statue flipped through her book and came to the titular recipe (right under one for Irish stew), and the ingredients read, Armenians, Africans, English, Dutch Cue scenes of people of various ethnicities diving into the water in a giant pot (with a handle), apparently on a stove. One of the verses declared, You simply melt right in/It doesnt matter what your skin/It doesnt matter where youre from/Or your religion, you jump right in/To the Great American Melting Pot.

I found it puzzling, maybe even a little disturbing. As the grandson of Assyrian immigrants, I wondered, Is that what really happens? We melt right in? Isnt that painful? Im sure I wasnt sophisticated enough to be thinking about the true impact on my grandparents culture, but I remember wondering about the previous lives of all those people simmering in that pot. Much later, I thought, What about the Native Americans who were already here? Did they melt right in, too? Did they want to?

The original melting-pot metaphor for homogeneity was actually a crucible or a smelting pot, not a cooking pot. Im not sure if that episode of Schoolhouse Rock! was the first time the metaphor was translated into a culinary context, but it seemed to stick because I remember my social studies teacher discussing the song with us many years later when I was in high school. He said that a more accurate metaphor would be that of a salad bowl, with the distinct elements intact. Or perhaps a bouillabaisse. I immediately liked those ideas better (although Im sure I had no idea what bouillabaisse was).

What does all this have to do with the cookbook youre now reading about American food and American cooks? Well, when we ask the question, What is American food? we might as well be asking, What is America? Because the answer is every bit as complexmuch more complex than a melting pot, a salad, or a fish soup.

American food is native food, and it is immigrant food. It is food cooked in a spirit of openness, experimentation, and reinvention, but often with a deep attachment to tradition. It is a stew concocted in Santa Fe from the crops known as Three Sisterscorn, squash, and beanswhich are so important to Native American food culture. It is a sweet potato taco with almond salsa, feta, and green onion made by the son of Mexican immigrants in an LA food truck. It is, of course, a hamburger and milkshake served from a quintessential 1950s-era drive-in found in the heart of the Midwest; and it is a burnished loaf of challah, perfectly braided in DC by one of the worlds foremost experts in Jewish cuisine. It is the matcha-dusted snickerdoodles dreamed up by a brilliant pastry chef in Chicago; it is the gumbo that an iconic ambassador of Creole cooking has been dishing out in New Orleans for decades; and it is the stir-fried tomatoes and eggs that a radio host and food writer in New York remembers his Chinese immigrant mother making for him when he was a kid.

Those examples are among the flavors and personalitiessome of them famouswe have captured in this collection. Their recipes are wonderful, but this book is not just about how many cups of flour go into a cake. We think weve captured the essence of what it means to be American through the eyes and hands and mouths and words of some of our favorite chefs, producers, and home cooks. The portraits of these people and their places are also a portrait of our collective place, as disjointed as it might sometimes seem. Out of many, one.

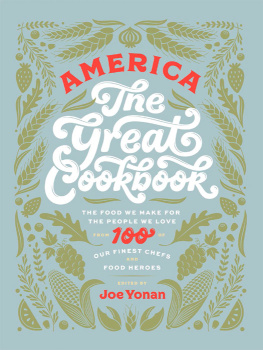

To capture just how special we think this portrait is, we commissioned Jessica Hische, star artist-typographer-illustrator, to come up with a unique, hand-lettered cover that celebrates the creativity, energy, and passion of every cook in this book. We hope you agree that she has nailed itand so have they.

This book is more than a celebration, though. Its also a call to arms against one of the most pressing issues of our time: poverty and a lack of access to good food, particularly among the most vulnerable of our community, our children. We are proud to promote this collection as a way to benefit No Kid Hungry and its tireless work toward eradicating child hunger. No child should have to face a single day uncertain about when and from where his or her next meal will come. Our children are Americas future, and we will not neglect them.

Back to that bowl of gumbo. Now that I think of it, gumbo just might be my favorite metaphor for this project, and indeed for the influence of so many rich cultures on American cuisine. Because as complex and as wonderful as a bowl of gumbo is, heres the thing: There are as many gumbos as there are cooks. As critic Brett Anderson once wrote in the New Orleans newspaper the Times-Picayune , There is no one gumbo history. There are countless histories.

And so it is with this ever-evolving thing called American food: Were not a melting pot, and neither is our cuisine. Were not a salad. Were not a burger. And were not a stewnot even, really, a gumbo. We are many, many gumbos, each one more delicious, more storied, and more satisfying than the last.

Leah Chase

OWNER AND EXECUTIVE CHEF OF DOOKY CHASES RESTAURANT

Gumbo is what were all about in New Orleans. We might have changed the course of America over a bowl of it right here in this restaurant. All the freedom riders met here before they went to the city to protest, and all I served them was gumbo and fried chicken. They made their plans and they headed out; some of them came back and some of them did not. Those who did come back were coming back to a bowl of gumbo. When you sit down to eat, you can iron out a whole lot of things. I always say, Come and sit down over a bowl of gumbo youll solve all the worlds problems.