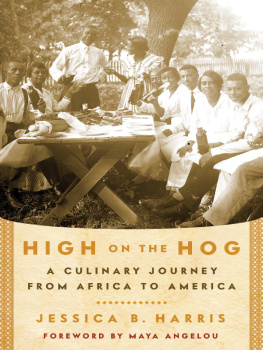

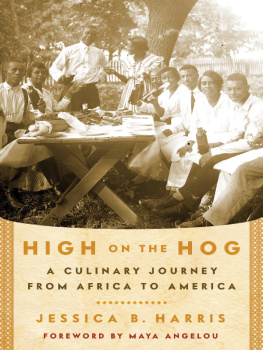

A CULINARY JOURNEY

FROM AFRICA TO AMERICA

JESSICA B. HARRIS

First and always to my late parents

Jesse Brown Harris and Rhoda Alease Jones Harris

And

To the Ancestors who slaved, served, survived, and

created a cuisine from a sows ear

To those past who used that food to nourish families,

grow fortunes, and connect communities

And

To the African American cooks, chefs, and culinary

entrepreneurs now and yet to come

Who honor the food, serve it up proudly, and keep the

circle unbroken.

CONTENTS

by Maya Angelou

O Freedom!

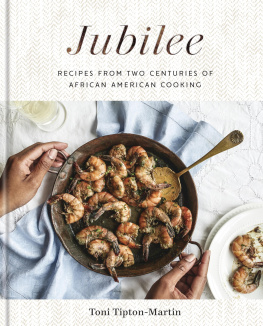

Jubilee Jubilations

BY MAYA ANGELOU

Jessica Harris, the well-known cook and cookbook author, has taken a great risk. She is already highly respected for the meticulous care she has shown in describing her recipes. She has been reliable in listing her sometimes exotic ingredients and where they can be found. However, in this new book she has offered only twenty recipes. Each is clear and well explained; still, the majority of High on the Hog is comprised of stories and essays written in well-chosen prose about food and how it traveled and made its impact on the world.

Harris has chosen African cookery and tracked its influence to the United States, to South America, and to the Ca rib be an. She shows explicitly how the culinary efforts changed the mores and cultures and people in each place. She has left little room for argument with her findings. I do, however, wonder if Ms. Harris is about to change permanently her ways of producing books.

Because I had written many books and had taught many classes years ago, I thought I was a writer who could teach. When I took the risk of accepting a permanent job teaching, I found I was not a writer who could teach, but a teacher who could write.

If Harris decides that she is more a prose writer than a recipe writer, the world of cookbook users and readers will be poorer for it. However, because she writes so well, all readers will be well serviced.

I will be among that group.

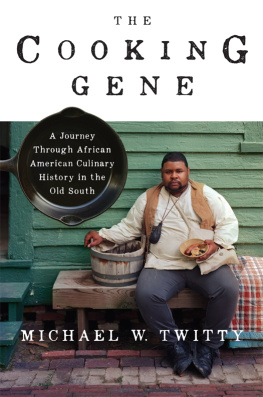

I am an African American. My family comes from here and can trace itself on both sides back over much of the period documented in this book. Therefore I know intimately, and am linked by blood to, the tastes of pig meat and cornmeal that are a part of this countrys African American culinary heritage. Ive spent more than three decades writing about the food of African Americans and how it connects with other cuisines in the hemisphere and around the world, and so I also know that the food of the African continent and its American diaspora continues to remain a culinary unknown for most folks.

The history of African Americans in this country is a lengthy one that begins virtually at the time of exploration. Our often-hyphenated name, in all of its complexity, hints at the intricate mixings of our past. We are a race that never before existed: a cobbled-together admixture of Africa, Europe, and the Americas. We are like no others before us or after us. Involuntarily taken from a homeland, molded in the crucible of enslavement, forged in the fire of disenfranchisement, and tempered by migration, we all too often remain strangers in the only land that is ours. Despite all this, we have created a culinary tradition that has marked the food of this country more than any other. Our culinary history is fraught with all the associations with slavery, race, and class that the United States has to offer. For this reason, the traditional foodways that derive from the history of enslavement that many of us share are often perceived as unhealthy, inelegant, and hopelessly out of sync with the culinary canons that define healthy eating today.

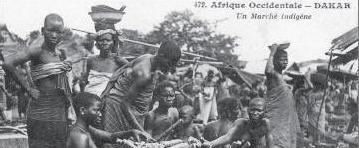

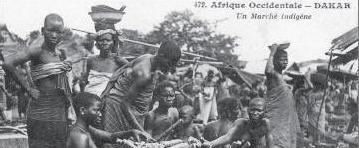

Yet, for centuries, black hands have tended pots, fed babies, and worked in the kitchens of this countrys wealthiest and healthiest. The disrespect for our food and for the people who cook it has been a battle that has raged for decades. Ebony magazines first food editor, Freda DeKnight, wrote about it in the introduction to her 1948 cookbook, Date with a Dish: It is a fallacy, long disproved, that Negro cooks, chefs, caterers, and homemakers can adapt themselves only to the standard Southern dishes, such as fried chicken, greens, corn pone and hot breads. More than a half century after the books publication, at a period when chefs have become empire builders and media millionaires, that debate still rages. Certainly I will have much to say about slave markets, both those in which my ancestors were sold and others where my ancestors and those like them sold goods that theyd grown and items that theyd prepared. I will speak of scant meals of hog and hominy and of simple folk who became culinary entrepreneurs, like illiterate Pig Foot Mary, who created a real estate empire from the food that she cooked on an improvised stove on the back of a baby carriage!

I will also speak of presidential chefs like George Washingtons Hercules and Thomas Jeffersons James Hemings and of an alternate African American culinary thread that weaves through the fabric of our food. This parallel thread is a strong one and includes Big House cooks who prepared lavish banquets, caterers who created a culinary co-operative in Philadelphia in the nineteenth century, a legion of black hoteliers and culinary moguls, and a growing black middle and upper class.

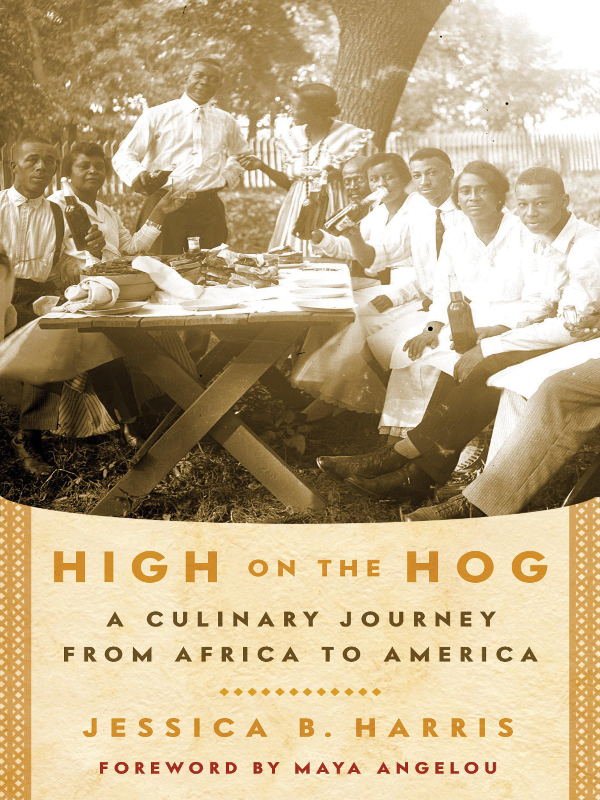

My family is a part of that middle class and encapsulates both culinary threads. In 1989, I wrote in Iron Pots and Wooden Spoons: Africas Gifts to New World Cooking, Fate has placed me at the juncture of two Black culinary traditions: that of the Big House and that of the rural South. The Jones side of the family always held reunions at table. Early childhood memories are filled with images of groaning boards, of put up preserved peaches, seckle pears, and watermelon rinds, of cool drinks such as minted lemonade, of freshly baked Parker House rolls and yeast breads. The Harris side of the family were no slouches at chowing down either. Grandma Harris insisted on fresh produce, and some of my early memories are of her gardening in a small plot where she lived.

Writing about the food of African Americans connects me to my forebearers. On one side of the family was Samuel Philpot, who was born enslaved in Virginia and in his thirties at the time of Emancipation. My mother knew him, and I have several photographs of him, as he lived to be more than one hundred years of age. He was reputed to have been a Big House servant who on one occasion served Abraham Lincoln at supper. He married the daughter of free people of color, settled in Virginia, near Roanoke, and became the progenitor of the Jones side of my family. On the Harris side of the family, my great-grandmother Merendy Anderson had an orchard in the post-Emancipation period where she grew stone fruitplums, peaches, and moreand sold them to neighbors in her Tennessee town. Closer to me were both of my grandmothers, who embodied the culinary traditions of their families. Grandma Harris cooked little and not particularly well, but she made beaten biscuits and could put a hurtin on a mess of greens. She read her Bible and wrote poetry, but was plainspoken, a vestige of her struggle with literacy. Grandma Jones was more eloquent on paper; shed gone to a womens seminary in Virginia in the late nineteenth century and embodied all the elegance that that state claims at table.

Next page