Hog & Hominy

ARTS & TRADITIONS OF THE TABLE

ARTS & TRADITIONS OF THE TABLE

PERSPECTIVES ON CULINARY HISTORY

Albert Sonnenfeld, Series Editor

Salt: Grain of Life

Pierre Laszlo, translated by Mary Beth Mader

Culture of the Fork

Giovanni Rebora, translated by Albert Sonnenfeld

French Gastronomy: The History and Geography of a Passion

Jean-Robert Pitte, translated by Jody Gladding

Pasta: The Story of a Universal Food

Silvano Serventi and Franoise Sabban, translated by Antony Shugar

Slow Food: The Case for Taste

Carlo Petrini, translated by William McCuaig

Italian Cuisine: A Cultural History

Alberto Capatti and Massimo Montanari, translated by ine OHealy

British Food: An Extraordinary Thousand Years of History

Colin Spencer

A Revolution in Eating: How the Quest for Food Shaped America

James E. McWilliams

Sacred Cow, Mad Cow: A History of Food Fears

Madeleine Ferrires, translated by Jody Gladding

Molecular Gastronomy: Exploring the Science of Flavor

Herv This, translated by M. B. DeBevoise

Food Is Culture

Massimo Montanari, translated by Albert Sonnenfeld

Kitchen Mysteries: Revealing the Science of Cooking

Herv This, translated by Jody Gladding

Gastropolis: Food and New York City

Edited by Annie Hauck-Lawson and Jonathan Deutsch

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2008 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-51797-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

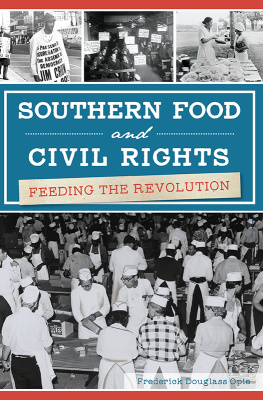

Opie, Frederick Douglass.

Hog and hominy : soul food from Africa to America / Frederick Douglass Opie.

p. cm (Arts and traditions of the table)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-14638-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-14639-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-51797-3 (e-book)

1. African American cookeryHistory. 2. African AmericansFoodHistory. 3. African AmericansSocial life and customs. 4. Cookery, AmericanSouthern styleHistory. 5. CookeryAmericanHistory. 6. Food habitsAmericaHistory. 7. BlacksFoodAmericaHistory. 8. BlacksAmericaSocial life and customs. 9. Cookery, AfricanHistory. 10. Food habitsAfricaHistory.

I. Title. II. Series

TX715.0548 2008

641.59296073DC22 2008020309

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

DESIGN & TYPESETTING BY vin dang

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO Super, the nickname of my paternal grandfather, Fred Opie, Sr., whom I never met but heard so much about, as well as to Grandma Opie, whose minced meat and rhubarb pies kept me happy and full. The book is also dedicated to Luesta Duers, the gracious matriarch on my mothers side and my maternal grandmother. Finally, the book is dedicated to my wife, Tina, and my children, Kennedy Kwabena and Chase Asabe Opie. Thanks for helping me maintain a balanced life while I researched and wrote this book over the last seven years.

Contents

The culinary tradition known as soul food has been widely celebrated, as jazz music has been celebrated, as part of African American culture. This book offers a broad look at the history of soul food, as it came to be called during the black power movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and at its social and religious meanings, particularly its relationship to the concept of soul itself. In recent years, many food scholars, food enthusiasts, cookbook authors, and others have debated what events, forces, and movements shaped the development of African American foodways, but few have turned their attention to tracing the concept of soul in African American foodways, where it appeared long before the name soul food was coined.

In the course of my research for this project, I have arrived at multiple definitions of soul and soul food. As I understand it, soul is the product of a cultural mixture of various African tribes and kingdoms. Soul is the style of rural folk culture. Soul is black spirituality and experiential wisdom. And soul is putting a premium on suffering, endurance, and surviving with dignity. Soul food is African American, but it was influenced by other cultures. It is the intellectual invention and property of African Americans. Soul food is a fabulous-tasting dish made from simple, inexpensive ingredients. Soul food is enjoyed by black folk, whom it reminds of their southern roots. This book argues, then, that soul is an amalgamation of West African societies and cultures, as well as an adaptation to conditions of slavery and freedom in the Americas. African Americans developed a cultural identity through soul and the associated foodways of people of African descent over hundreds of years.

This project seeks to understand the history of soul and its relationship to people of African descent and their food within an Atlantic world context. This required investigating the traditions of Africans and the culinary traditions they absorbed from Europeans, especially Iberians. I also had to take into account the influence of Asian food. In doing so, I build on the pioneering work of Helen Mendes, Verta Mae Grosvenor, Sidney W. Mintz, Karen Hess, Howard Paige, Jessica Harris, and, most recently, Psyche Williams-Forson.

The African American ideologues of soul food, with the exception of Verta Mae Grosvenor, failed to embrace and incorporate cuisines of other peoples of African descent migrating to the United States from the Caribbean after the turn of the century. Their concept of soul food evolved during the black power era of the 1960s and was largely exclusionary of other cuisines of the African diaspora present in U.S. urban communities. Partisans of the soul ideology juxtaposed southern black cuisine and southern black folkways against what they perceived as a dominant white culture, and they defined southern-based black cuisine as a marker of cultural blackness. But where does that place the equally African-influenced cuisines that began to proliferate in multiethnic communities of color in, for example, metropolitan New York as early as the 1930s? This book takes a more inclusive approach to the development of black urban food markers of identity that argues that jerked chicken, empanadas, patties, cucu, coconut bread, mafungo, mangu, chicharrones, ropa vieja, and fried plantains, to name just a few foods, are as much soul food as collards, Hoppin John, fried chicken, corn bread, and sweat potato pie. A trip to New York, Miami, Boston, Bridgeport, Hartford, or scores of other urban centers reveals that for every soul food restaurant today, there are many more Caribbean restaurants. And the cuisines of those restaurants are at least as African influenced as any southern soul food.

Next page