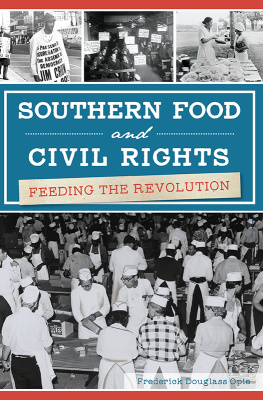

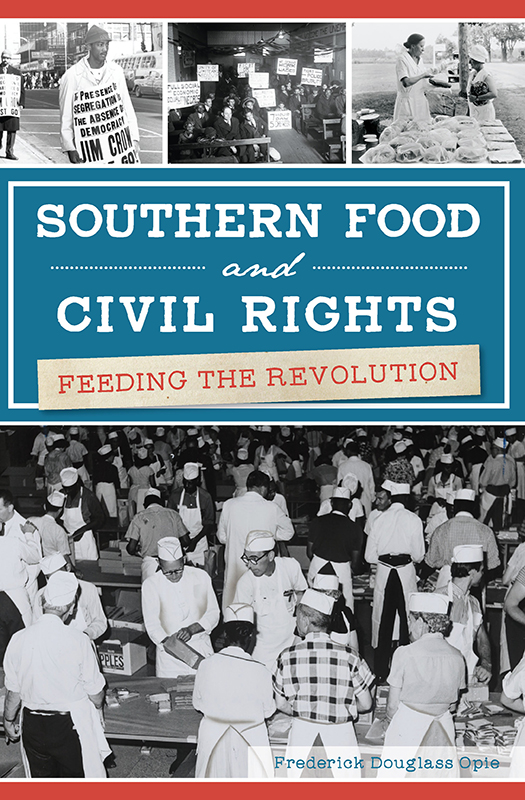

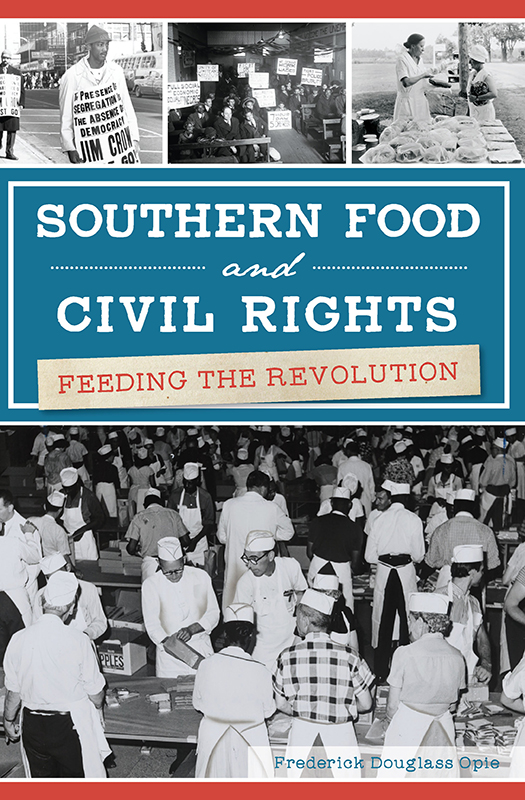

Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2017 by Frederick Douglass Opie

All rights reserved

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.43965.921.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016950693

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.738.6

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Napoleon said that an army marches on its stomach, leading to the questions: What is the relationship between food and political stabilityor instabilityduring important periods in history? What role does food play in starting and sustaining a movement? And what important takeaways do we gain from looking at the role of food in social movements?

Southern Food and Civil Rights delves into the movements for progressive change that occurred from the 1920s through the 1960s and includes an afterword on the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement.

The final years of completing this book on food and social movements coincided with the release of the film The Help and its monolithic images of African Americans as subservient, poor victims. I also completed the book while several tragic deaths of African Americans occurred in Florida, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Maryland, Louisiana and Minnesota, and in some instances, riots and movements for social justice developed thereafter. After the death of Travon Martin in Florida, I, like others, watched the subsequent emergence of the decentralized Black Lives Matter movement, for which women served as principal strategists and spokespersons. This book looks at the precursors of contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter. It shows that there have always existed movements for social justice in this country, many of them in the southern United States, where African Americans lived in their greatest concentration from the colonial period until the 1960s. And food has been at the center of civil rights movements in one way or the other throughout that time.

This book looks at the organizations and individuals, home cooks and professional chefs, whowith the food they donated, cooked, grew and distributedhelped various activists continue to march and advance their goals for progressive change and self-determination. The book also looks at movements to end discrimination in the restaurant industry for customers and would-be employees, as well as the role food has played in the Nation of Islams economic empowerment initiatives.

Through this exploration of food and social justice, this book addresses such questions as how did African Americans view Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) and his National Recovery Administration (NRA) programs, particularly his job initiatives? What led to the end of Jim Crow policies in Washington, D.C. restaurants? How did progressive organizations raise the funds necessary to pay for their programs, staff and campaigns? How did striking hospital workers feed their families in New York City between 1959 in 1962? What individuals and groups made important food-related contributions to movements? How did the organizers of the March on Washington source and supply the sandwich brigade meant to provide food for the thousands of supporters who converged on the Mall in the nations capital in 1963? Where did organizers meet and strategize in the Jim Crow South, and where did white supremacists employ violent repression against activists? Do activists have favorite restaurants? Do activists observe food rituals and traditions during strategy meetings? Oral histories and newspaper accounts provide the bulk of the primary source materials used to answer these questions.

1

DONT BUY WHERE YOU CANT WORK

HISTORY OF THE MOVEMENT

In the 1920s, black newspapers informed their communities across the country about organizations dedicated to their interests. Many black neighborhoods had a local distributor of black papers that sold subscriptions to and delivered copies of the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Pittsburgh Courier, the Chicago Tribune, the New Journal & Guide, the Afro-American and the New York Amsterdam News to their customers. In most cases, African Americans in urban centers and some communities across the South could select from among several newspapers that agents offered. For example, in 1940s Tarrytown, New York, a suburb of New York City, literate African Americans subscribed to one or more of these papers and read them on a weekly basis.

African American newspapers depended largely on the national black wire service, the Chicago-based Associated Negro Press, for their content. As a result, stories on new black organizations and their activities that the wire service carried quickly traveled across the country.

In 1927, Chicagos Urban League chapter launched an unsuccessful campaign against the A&P grocery store company, which was refusing to hire African American clerks and managers. Two years later, the black-owned newspaper the Chicago Whip launched a Dont Spend Your Money Where You Cant Work boycott that mobilized black South Side residents in the citys Bronzeville section.

This chapter is a history of the genesis of the nonviolent direct-action movement that was the earliest of its kind and later became the distinguishing strategy of the U.S.and largely southerncivil rights movement. These Great Depressionera movements pioneered the civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 60s, both on the streets and in courts.

The available newspaper records provide more details on some movements than others. Nonetheless, the New Negro Alliance (NNA) in Washington, D.C., had the largest and most successful direct-action movement and the one with the most detailed documentation of the 1920s through the 1940s, the decades covered in this chapter. The movement in the nations capital included boycotts, picketing, the arrest of protesters and court cases, including the U.S. Supreme Court case New Negro Alliance et al. v. Sanitary Grocery Co., Inc. The March 1938 case had a profound effect on similar movements around the country and laid the foundation for future U.S. civil rights cases.

THE CHICAGO MOVEMENT

In 1929, community activists James Hale Porter, lawyer and Chicago Whip founder and editor Joseph D. Bibb and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) executive committee member and Whip managing editor A.C. MacNeal created the Dont Spend Money Where You Cant Work campaign. The movement focused on generating jobs for unemployed black workers on the South Side of Chicago.

An A&P Super Market in 1940. Courtesy of Library of Congress

Next page